Many thanks to Stephen Mihm of the University of Georgia (author of the outstanding A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States) for his cover story in the Ideas section of the Boston Globe on crowdsourcing and history. I’m grateful for his coverage of the Center for History and New Media‘s many collecting projects, and for featuring my remarks so prominently.

Category: History

-

-

Enhancing Historical Research With Text-Mining and Analysis Tools

I’m delighted to announce that beginning this summer the Center for History and New Media will undertake a major two-year study of the potential of text-mining tools for historical (and by extension, humanities) scholarship. The project, entitled “Scholarship in the Age of Abundance: Enhancing Historical Research With Text-Mining and Analysis Tools,” has just received generous funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

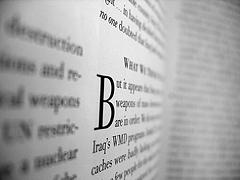

I’m delighted to announce that beginning this summer the Center for History and New Media will undertake a major two-year study of the potential of text-mining tools for historical (and by extension, humanities) scholarship. The project, entitled “Scholarship in the Age of Abundance: Enhancing Historical Research With Text-Mining and Analysis Tools,” has just received generous funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.In the last decade the library community and other providers of digital collections have created an incredibly rich digital archive of historical and cultural materials. Yet most scholars have not yet figured out ways to take full advantage of the digitized riches suddenly available on their computers. Indeed, the abundance of digital documents has actually exacerbated the problems of some researchers who now find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of available material. Meanwhile, some of the most profound insights lurking in these digital corpora remain locked up.

For some time computer scientists have been pursuing text mining as a solution to the problem of abundance, and there have even been a few attempts at bringing text-mining tools to the humanities (such as the MONK project). Yet there is not as much research as one might hope on what non-technically savvy scholars (especially historians) might actually want and use in their research, and how we might integrate sophisticated text analysis into the workflow of these scholars.

We will first conduct a survey of historians to examine closely their use of digital resources and prospect for particularly helpful uses of digital technology. We will then explore three main areas where text mining might help in the research process: locating documents of interest in the sea of texts online; extracting and synthesizing information from these texts; and analyzing large-scale patterns across these texts. A focus group of historians will be used to assess the efficacy of different methods of text mining and analysis in real-world research situations in order to offer recommendations, and even some tools, for the most promising approaches.

In addition to other forms of dissemination, I will of course provide project updates in this space.

[Image credit: Matt Wright]

-

Roy Rosenzweig Prize in History and New Media

A very special announcement of a new prize from the American Historical Association and the Center for History and New Media. The Rosenzweig Prize will be awarded annually for an innovative and freely available new media project that reflects thoughtful, critical, and rigorous engagement with technology and the practice of history.

-

Digital History at the AHA Annual Meeting

The American Historical Association‘s blog has a recap of some of the the digital history events at the annual meeting in Washington, DC.

-

Journal of American History Interchange on Digital History

Starting today and running for the next month, I’ll be joining a half-dozen other professors in a discussion on the Journal of American History website on the promise and challenges of digital history. It’s great that the JAH is providing this forum and publishing the results in their September 2008 issue. I’m hoping they’ll open up the live discussion to the public, but it seems unlikely since they want to redact the text for publication. I’ll try to mention interesting topics that arise in the discussion in this space.

-

MacEachern and Turkel, The Programming Historian

Bill Turkel, the always creative mind behind Digital History Hacks (logrolling disclosure: Bill is a friend of CHNM, a collaborator on various fronts, and was the thought-provoking guest on Digital Campus #9; still, he deserves the compliments), and his colleague at the University of Western Ontario, Alan MacEachern, are planning to write a book entitled The Programming Historian. Better yet, the book will be open access and hosted on the Network in Canadian History & Environment (NiCHE) site. Bill’s summary of the book on his blog sounds terrific. Can’t wait to read it and use it in my classes.

-

Using New Technologies to Explore Culture Heritage Conference

Following a nice evening at the Italian Embassy, the conference “Using New Technologies to Explore Cultural Heritage,” jointly sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR, Italy’s National Research Council), kicked off at the headquarters of the NEH in Washington. Sessions included “Museums and Audiences,” “Virtual Heritage,” “Digital Libraries: Texts and Paintings,” “Preserving and Mapping Ancient Worlds,” and “Monuments, Historic Sites, and Memory.” The discussion was wide-ranging and covered topics both digital and analog.

Museums and Audiences

In the morning, Francesco Antinucci, the Director of Research at CNR, showed the audience some fairly depressing statistics about visitors to (physical) museums. There are 402 state museums in Italy, but only a few of them have large numbers of visitors–even though many of them have fantastic collections that are basically equivalent to the popular ones. For instance, the museum at Pompeii receives six times the visitors of Herculaneum, even though both were destroyed at the same time and Herculaneum is better-preserved and arguably has a better museum. Name recognition and museum “brands” clearly matter–a lot.

To make matters worse for cultural heritage sites, studies of museum visitors show that about half completely fail to remember what was in a gallery after they leave it. When asked, many can’t name a single painter or painting, even the gigantic, striking Caravaggio at the center of one of the galleries they studied.

Unfortunately, visitors to museum websites are equally disengaged. The average visit is one minute to the sites of the Italian state museums, and very few visitors are doing real research on these sites. In both the real and virtual world, we need to figure out how to reach and involve visitors.

In the discussion of Antinucci’s presentation, Andrew Ackerman, the Executive Director of the Children’s Museum of Manhattan (who had just presented on his museum’s new antiquities wing for kids), argued that museums and websites have to engage people with a wider variety of styles of learning and presentation. Others wondered if new technologies like podcasts and vodcasts might help. One very good point (again, by Ackerman) was that museums do a very poor job providing an overview and navigation to new visitors. The top two questions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York are “Where are the restrooms?” and “Where is the art?”

Virtual Heritage

Maurizio Forte, a senior researcher at CNR’s Institute for Technologies Applied to Cultural Heritage, showed off some new technologies that are revolutionizing archaeology, including Differential GPS, digital cameras (on balloons and kites), and mapping software. What’s interesting about these technologies is how inexpensive they now are. This has allowed archaeologists to begin to create top-notch 3D modeling and maps for the 85% of archaeological sites that have only had poor hand sketches or no maps at all. New display technologies allow scholars to take these maps and recreate sites in vivid virtual representations, or move them into Second Life or other virtual worlds for exploration.

These 3D displays have the great virtue of being compelling eye candy (and thus great for engaging students who can fly through a historic site as in a video game, as Steven Johnson would argue) while also truly providing helpful environments for scholarly research. For instance, you can see the change of a city across time, or really understand the spatial relations between civic and religious buildings in a square.

Bernard Frischer of UVa agreed that “facilitating hypothesis formation” was a key reason to make high-quality virtual models. Frischer showed how an extensive digital model can blend real-world measurements, digitally reborn versions of buildings, and born-digital additions of elements that may no longer be present at a site. The result of this melding is very impressive in Rome Reborn 1.0.

Digital Libraries: Texts and Paintings

Andrea Bozzi, the Director of Research at CNR’s Institute for Computational Linguistics, discussed the new field of computational philology–using computational means to recover and understand ancient (and often highly degraded) texts such as Greek papyri and broken ceramics. Fragments of words can be deciphered using statistics and probability.

Massimo Riva, a Brown University Professor, presented Decameron Web, an archive completely built by teachers and students; a site for the collaborative annotation of the work of Pico della Mirandola; and the Virtual Humanities Lab, which also allows for collaborative annotation of texts. I’ve been meaning to blog about the rise of many online annotation tools; I’ll add these examples to my running list and hopefully post an article on the movement soon.

Preserving and Mapping Ancient Worlds

Massimo Cultraro, a researcher at CNR’s Institute for Archaeological Heritage, Monuments, and Sites, spoke about the “Iraq Virtual Museum” CNR is building–in part to reestablish online much of what was lost from looting and destruction during the war. The website will include virtual galleries of artifacts from the many important eras in Mesopotamian history, including Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Achaemenid, Hatra, and Islamic works. They are making extensive use of 3D modeling software and animation; the introductory video for the site is almost entirely movie-quality computer graphics. (The site has not yet launched; this was a preview.)

Richard Talbert, a professor of ancient history, and Sean Gillies, the chief engineer at the Ancient History Mapping Center, both from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, presented the Pleiades Project, which is producing extensive data and maps of the ancient world. Talbert and Gillies emphasized up front the project’s open source software (including Plone as a foundation) and very open Creative Commons license for their content–i.e., anyone can reuse the high-quality maps and mapping datasets they have produced. Content can be taken off their site and moved and reused elsewhere freely. They advocated that scholars doing digital projects read Karl Fogel’s Producing Open Source Software and join in this open spirit.

The openness and technical polish of Pleiades was extraordinarily impressive. Gillies showed how easy it was to integrate Pleiades with Yahoo Pipes, Google Earth (through KML), and OpenLayers (an open competitor to Google Maps). (This is just the kind of digital research and interoperability that we’re hoping to do in the next phase of Zotero.) Pleiades will allow scholars to collaboratively update the dataset and maps through an open-but-vetted model similar to Citizendium (and unlike free-for-all Wikipedia). Trusted external sites can use GeoRSS to update geographical information in the Pleiades database. The site–and the open data and underlying software they have written–will be unveiled in 2008.

Monuments, Historic Sites, and Memory

Gianpiero Perri, the managing director of Officina Rambaldi, discussed the development and integration of a set of technologies–including Bluetooth, electronic beacons, and visual and digital cues–to provides visitors with a more rich experience of the pivotal World War II battle at Cassino. He called it a new way to engage historical memory through the simultaneous exploration of the landscape and exhibits online and off, but it was a little unclear (to me at least) what exactly visitors would see or do.

Arne Flaten, a professor of art history at Coastal Carolina University, presented Ashes2Art, “an innovative interdisciplinary and collaborative concept that combines art history, archaeology, web design, 3D animation and digital panoramic photography to recreate monuments of the ancient past online.” All of the work on the project is done by undergraduates, who simultaneously learn about the past and how to use digital modeling programs (like Maya or the free Sketchup) for scholarly purposes. A great model for other undergrad or grad programs in the digital humanities. Like Pleiades, the output of this project is freely available and downloadable.

-

The Artistic and the Digital

Roy Rosenzweig and I begin our book Digital History with a list of the advantages and disadvantages of digital media and technology for the practice of history. The “dangers or hazards” include questions about quality, durability, readability, passivity, and inaccessibility. Although scholars in the humanities fret about these hazards, my experience at several art meccas over the last few days has made me think that a supposedly less conservative (small “c” conservative) group than historians—artists—is having even more trouble adjusting to the realities of the digital age.

We are fortunate here on vacation in East Chatham, NY, to be equidistant from several incredible museums. No one should visit the Berkshires without making a trip to the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., of course. But it was my experience at Olana, the outrageously designed and decorated house of one of the great nineteenth-century American artists, Frederick Edwin Church, and at MASS MoCA, the center for contemporary art in North Adams, Mass., that made me wonder whether artists can handle the impact of digital technology.

At first blush, contemporary art is full of early adopters. Photography, film, video, and Photoshop were quickly taken up by artists in the twentieth century. And several iMacs were part of MASS MoCA’s collection. (Best use of an iMac: to beam the brainwaves of the artist Spencer Finch to the star Rigel as he watched a one-second loop of the giant wave from the beginning of the TV show “Hawaii Five-O.” As the exhibition description notes with no discernible humor, “Finch’s wave is expected to arrive at its destination in the year 2956.”)

[Spencer Finch, Sunlight in an Empty Room (Passing Cloud for Emily Dickinson, Amherst, MA, August 28, 2004), 2004.]

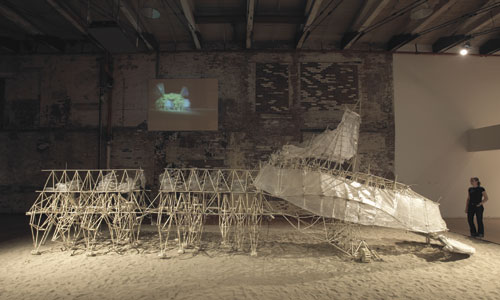

But MASS MoCA’s collections were filled with the products of technically savvy artists who have rejected placing their art in the digital realm. Panamarenko, the Belgium artist obsessed with modern technology (his pseudonym is a jokey contraction of “Pan American Airlines,” one of his obsessions), makes fussy, fragile replicas of dirigibles and other aircraft. Some may remember the Dutch physicist-turned-artist Theo Jansen’s early art, computer programs that presented digital worms replicating themselves on the screen. Jansen has long since abandoned his computer. His new artwork, easily the great highlight of MASS MoCA’s current collection, are Strandbeest, amazing robotic creatures he has fashioned out plastic rods and canvas. Conspicuously absent from the Strandbeest are on-board computers or any electronic devices—they move along the beach like giant crabs by picking up the wind in their canvas sails.

[Theo Jansen, Animaris Percipiere Primus, 2005.]

In short, the artists at MASS MoCA still feel that the height of art is to produce something physical, or a physical space, or a unique sensation, that can only be experienced by trekking to see their art. For them, art requires incarnation and uniqueness—elements that the digital realm is particularly efficient at destroying. Finch, a talented artist who uses a number of scientific instruments to create his art (colorimeters, computers), nevertheless sees real art as a single end product. Art cannot be placed on the web or uploaded to YouTube; it cannot tolerate near-infinite copies being traded across the internet like MP3s, the digital low-brow.

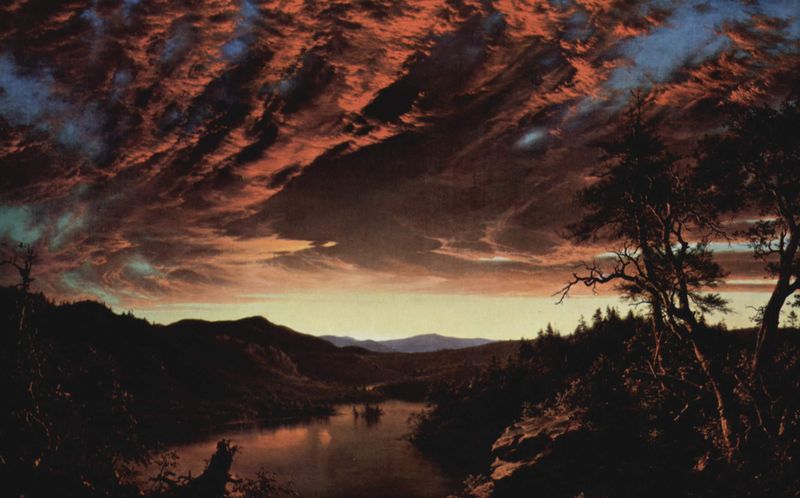

In this way, these artists are little different than Church. Church made a fortune on his art by selling massive (up to 5 foot by 10 foot) canvases with views of the American wilderness, the Andes, and the Middle East for equally massive prices. Like other Romantic and Victorian landscape painting, the experience of seeing a large Church canvas was like a ticket to a summer blockbuster (there were even tickets to see single paintings). No tiny reproduction would do. Similarly, Church spent decades trying to find just the right site and design for his house, which is indeed situated at perhaps the greatest overlook in the Hudson valley, with each window of the house framing a spectacular view that echoed Church’s optimistic, spiritual vision of American nature. (The Persian-by-way-of-Victorian decoration of the house is a little too busy for my tastes, but the views of out of the structure are breathtaking.)

[Frederick Edwin Church, Dawn in the Wilderness, 1860.]

Undoubtedly there are contemporary artists putting their work online, or giving copies away for free in a digital format, but my sense is that these artists are unlikely to show up in the Whitney Biennial, as Finch did in 2004. In the art world, it seems that the physical will for some time trump the digital.

-

Nineteenth-Century Open Source

Near where we’re staying on vacation there is a small but excellent Shaker museum. As a historian who in part studies nineteenth-century religion, I know a bit about the Shakers, one of the more remarkable and unusual revival Christian sects. (Note to those wishing to create a new sect that flourishes: eschew celibacy, even if you do make amazing furniture.) It is easy to think of the Shakers as from another age (or perhaps world), living in massive “families” of 50 to 100 “brothers and sisters” and focusing on the simple life of agriculture and crafts (in addition to very serious and often ecstatic forms of worship). But the museum brings to life the Shakers’ less well-known technological sophistication. They were innovators of the first order, constantly refining the efficiency of their families’ production (the simple lines of Shaker furniture made them easier to clean, important when your dining room seats 100).

Near where we’re staying on vacation there is a small but excellent Shaker museum. As a historian who in part studies nineteenth-century religion, I know a bit about the Shakers, one of the more remarkable and unusual revival Christian sects. (Note to those wishing to create a new sect that flourishes: eschew celibacy, even if you do make amazing furniture.) It is easy to think of the Shakers as from another age (or perhaps world), living in massive “families” of 50 to 100 “brothers and sisters” and focusing on the simple life of agriculture and crafts (in addition to very serious and often ecstatic forms of worship). But the museum brings to life the Shakers’ less well-known technological sophistication. They were innovators of the first order, constantly refining the efficiency of their families’ production (the simple lines of Shaker furniture made them easier to clean, important when your dining room seats 100).What really struck me was their patented technologies. That’s right, the sect occasionally took advantage of U.S. patent law. The Shaker family near us invented a massive, semi-automated washing machine, among other things. And what they did with their patents is most interesting. They patented these machines so that no one would steal the designs, and then they licensed the designs for free to other Shaker communities, which did the same in return with their innovations. Sound familiar?

[Photograph of a Shaker chair by chrisjfry.]

-

American Studies Tagline

Dave Lester provides an interesting visualization of the history of American Studies over the last fifty years by running Lucy Maddox’s Locating American Studies: The Evolution of a Discipline through a tag cloud creator and then putting it on a slider timeline. Note the rise and fall of Leo Marx’s influence on the field, among other things.