Roy Rosenzweig and I begin our book Digital History with a list of the advantages and disadvantages of digital media and technology for the practice of history. The “dangers or hazards” include questions about quality, durability, readability, passivity, and inaccessibility. Although scholars in the humanities fret about these hazards, my experience at several art meccas over the last few days has made me think that a supposedly less conservative (small “c” conservative) group than historians—artists—is having even more trouble adjusting to the realities of the digital age.

We are fortunate here on vacation in East Chatham, NY, to be equidistant from several incredible museums. No one should visit the Berkshires without making a trip to the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., of course. But it was my experience at Olana, the outrageously designed and decorated house of one of the great nineteenth-century American artists, Frederick Edwin Church, and at MASS MoCA, the center for contemporary art in North Adams, Mass., that made me wonder whether artists can handle the impact of digital technology.

At first blush, contemporary art is full of early adopters. Photography, film, video, and Photoshop were quickly taken up by artists in the twentieth century. And several iMacs were part of MASS MoCA’s collection. (Best use of an iMac: to beam the brainwaves of the artist Spencer Finch to the star Rigel as he watched a one-second loop of the giant wave from the beginning of the TV show “Hawaii Five-O.” As the exhibition description notes with no discernible humor, “Finch’s wave is expected to arrive at its destination in the year 2956.”)

[Spencer Finch, Sunlight in an Empty Room (Passing Cloud for Emily Dickinson, Amherst, MA, August 28, 2004), 2004.]

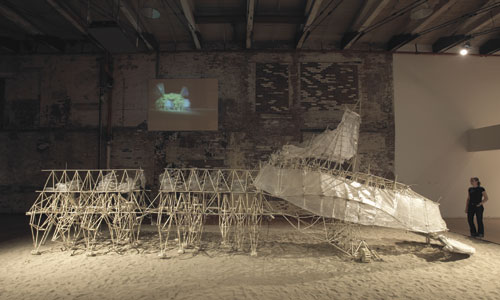

But MASS MoCA’s collections were filled with the products of technically savvy artists who have rejected placing their art in the digital realm. Panamarenko, the Belgium artist obsessed with modern technology (his pseudonym is a jokey contraction of “Pan American Airlines,” one of his obsessions), makes fussy, fragile replicas of dirigibles and other aircraft. Some may remember the Dutch physicist-turned-artist Theo Jansen’s early art, computer programs that presented digital worms replicating themselves on the screen. Jansen has long since abandoned his computer. His new artwork, easily the great highlight of MASS MoCA’s current collection, are Strandbeest, amazing robotic creatures he has fashioned out plastic rods and canvas. Conspicuously absent from the Strandbeest are on-board computers or any electronic devices—they move along the beach like giant crabs by picking up the wind in their canvas sails.

[Theo Jansen, Animaris Percipiere Primus, 2005.]

In short, the artists at MASS MoCA still feel that the height of art is to produce something physical, or a physical space, or a unique sensation, that can only be experienced by trekking to see their art. For them, art requires incarnation and uniqueness—elements that the digital realm is particularly efficient at destroying. Finch, a talented artist who uses a number of scientific instruments to create his art (colorimeters, computers), nevertheless sees real art as a single end product. Art cannot be placed on the web or uploaded to YouTube; it cannot tolerate near-infinite copies being traded across the internet like MP3s, the digital low-brow.

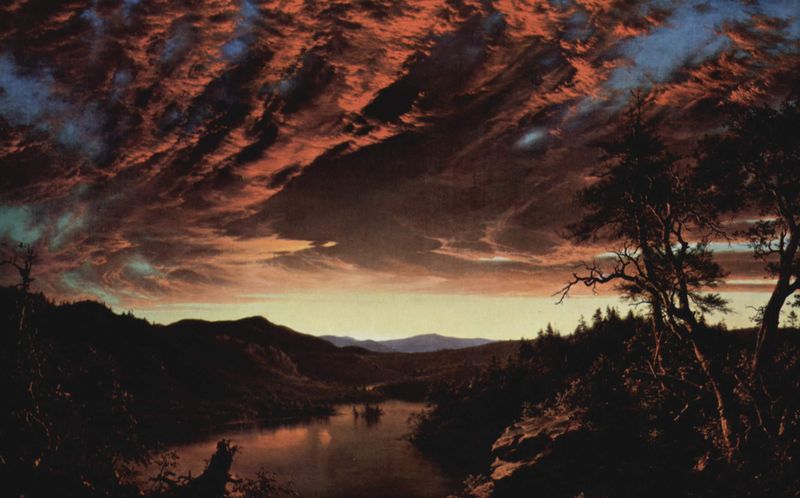

In this way, these artists are little different than Church. Church made a fortune on his art by selling massive (up to 5 foot by 10 foot) canvases with views of the American wilderness, the Andes, and the Middle East for equally massive prices. Like other Romantic and Victorian landscape painting, the experience of seeing a large Church canvas was like a ticket to a summer blockbuster (there were even tickets to see single paintings). No tiny reproduction would do. Similarly, Church spent decades trying to find just the right site and design for his house, which is indeed situated at perhaps the greatest overlook in the Hudson valley, with each window of the house framing a spectacular view that echoed Church’s optimistic, spiritual vision of American nature. (The Persian-by-way-of-Victorian decoration of the house is a little too busy for my tastes, but the views of out of the structure are breathtaking.)

[Frederick Edwin Church, Dawn in the Wilderness, 1860.]

Undoubtedly there are contemporary artists putting their work online, or giving copies away for free in a digital format, but my sense is that these artists are unlikely to show up in the Whitney Biennial, as Finch did in 2004. In the art world, it seems that the physical will for some time trump the digital.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.