This is what we know: On November 24, 2015, the Wu-Tang Clan sold its latest album, Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, through an online auction house. As one of the most innovative rap groups, the Wu-Tang Clan had used concepts for their recordings before, but the latest album would be their highest concept: it would exist as only one copy—as an LP, that physical, authentic format for music—encased in an artisanally crafted box. This album would have only one owner, and thus, perhaps, only one listener. By legal agreement, the owner would not be allowed to distribute it commercially until 88 years from now.

Once—note the singularity at the beginning of the album’s title—was purchased for $2 million by Martin Shkreli, a young man who was an unsuccessful hedge fund manager and then an unscrupulous drug company executive. This career arc was more than enough to make him filthy rich by age 30.

Then, in one of 2015’s greatest moments of schadenfreude, especially for those who care about the widespread availability of quality healthcare and hip hop, Shkreli was arrested by the FBI for fraud. Alas, the FBI left Once Upon a Time in Shaolin in Shkreli’s New York apartment.

Presumably, the album continues to sit there, in the shadows, unplayed. It may very well gather dust for some time.

This has made many people unhappy, and some have hatched schemes to retrieve Once, ideally using the martial arts the Shaolin monks are known for. But our obsession with possessing the album has prevented us from contemplating the nature of the album—its existence—which is what the Buddhists of Shaolin would, after all, prefer us to do.

RZA, the leader of the Wu-Tang Clan, had tried to forewarn us. As he told Forbes, “We’re about to put out a piece of art like nobody else has done in the history of music…This is like someone having the scepter of an Egyptian king.”

Many have sought ways that the public might listen to Once, but few have taken RZA at his word. What if Once Upon a Time in Shaolin is meant primarily as art, as a precious artifact that only one person, like a king, can hold? And if we consider this question, do we really need to listen to the album to hear what it’s saying?

* * *

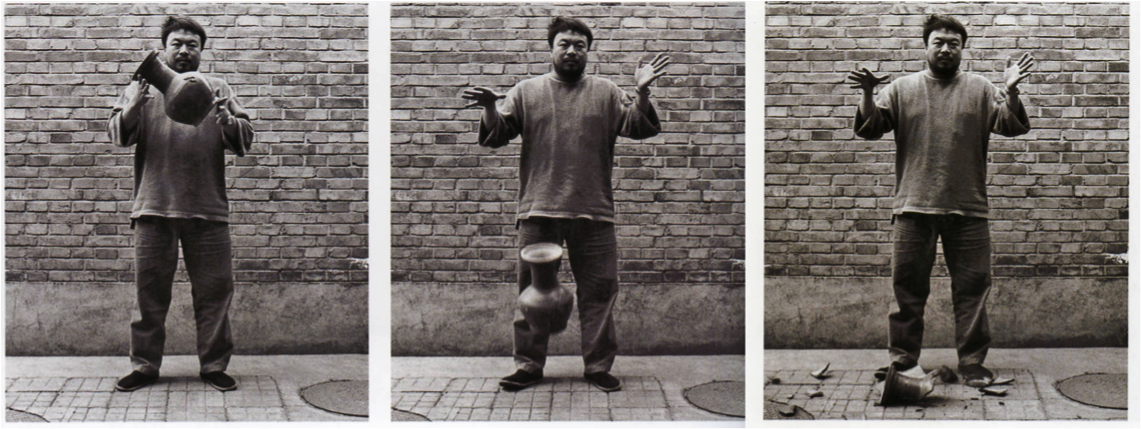

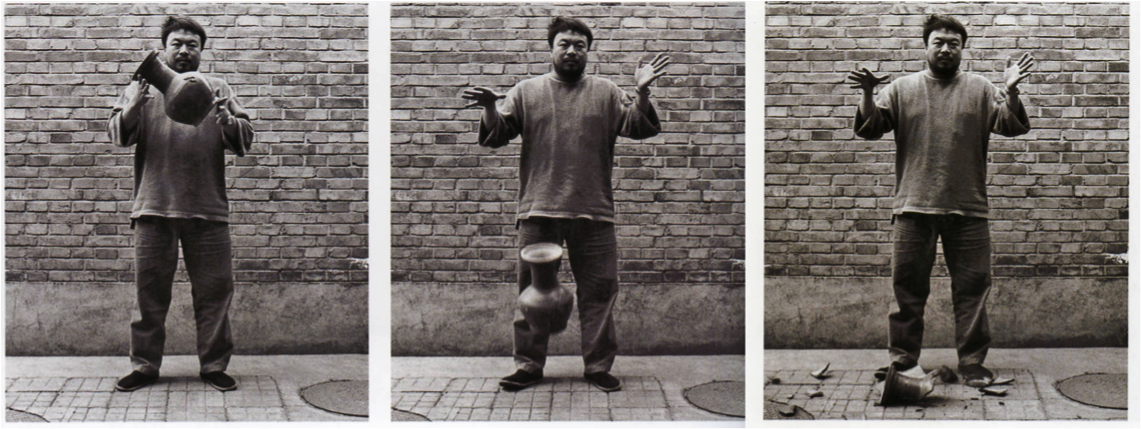

In 1995, the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei took an ancient, priceless Han Dynasty vase and dropped it onto a brick floor. It instantly shattered. He took a series of high-speed photographs of the vase drop, which he assembled into a triptych; in the middle photograph the vase seems like it’s in a levitating, suspended state. It exists, but it is milliseconds from not existing. It is forever there, whole, and yet we know it is forever in pieces.

He shouldn’t have destroyed that singular vase, you may be thinking. You must think more deeply, and enter the Shaolin temple of your mind.

* * *

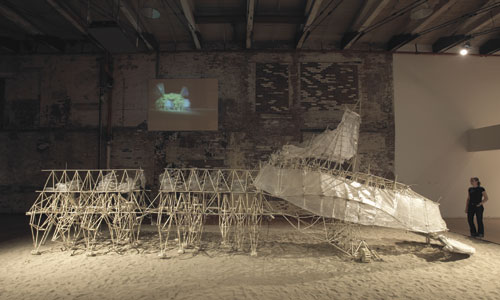

In the old mill town of North Adams, Massachusetts, a cluster of nineteenth-century factory buildings has been converted into the largest museum of contemporary art in the United States: Mass MoCA. One entire building, from top to bottom, is dedicated to the work of Sol LeWitt.

Sol LeWitt is an unusual artist in that he rarely painted, drew, or sculpted the art you see by him. Instead, he wrote out instructions for artwork, and then left it to “constructors”—often art students, museum curators, or others, to do the actual work of fabrication. LeWitt liked to be a recipe writer, not a chef.

“Wall Drawing 1180: Within a circle draw 10,000 straight black lines and 10,000 black not straight lines. All lines are randomly spaced and equally distributed.”

Somehow, incredibly, this ends up looking like a massive picture from the Hubble Telescope: an infinite field of stars emerges after weeks of drawing thousands of squiggly and straight lines with a pencil.

Sixty-five art students and artists, none of them Sol LeWitt, made the Sol LeWitt exhibit, and it is one of the most beautiful things you’ll ever see. The patterns, the colors, the way that LeWitt’s often deceptively simple recipes result in a sumptuous banquet for the eyes, is remarkable.

But the exhibit will only last for 25 years—eight of which have already ticked by—after which the museum will paint over all of the art. Touring the exhibit, you can’t help but think about this endtime: All of this beauty, and yet on some Monday morning in the not-really-that-distant future some guy with a 5-gallon bucket of white paint from Home Depot and a wide roller brush on the end of a long wood handle will cover those walls forever. Will he sigh before making the first stroke?

Until that Monday morning in 2033, the Sol LeWitt exhibit exists. You have 17 years remaining, but time moves more quickly than we like, doesn’t it? I have told you to see it, but will you make the trip to North Adams? Right now, for those who have not seen it, it’s Ai Weiwei’s Han vase in mid-drop. It’s just that the gravity is lighter, the fall slower. But the third photograph, the smashed pieces, is coming.

Do you fear the loss of that magical field of stars and scores of other wall-sized artworks? Or have you closed your eyes, meditated, and concluded: Even if I never get to North Adams, LeWitt’s recipes will still exist, and they are the true art.

* * *

In 2008, as Mass MoCA was constructing the Sol Lewitt exhibit, they also hosted an exhibit of the art of Spencer Finch. Finch was fascinated by Emily Dickinson, and wished to recreate the moments in which she looked out of her window, thinking and writing poetry. Could these ephemeral views be recaptured, made physical for us so many years later?

“Sunlight in an Empty Room (Passing Cloud for Emily Dickinson, Amherst, MA, August 28, 2004),” tried to do so. Finch used lighting and light filters to make a cloud of just the right wavelengths that Dickinson would have seen outside of her bedroom on a particular day.

You cannot capture a moment, you mutter softly, waving your hand, nor Emily Dickinson’s thoughts.

* * *

Open your favorite streaming music app, and search for the blockbuster 2013 song “Get Lucky.”

Make a playlist that includes the original Daft Punk version, which should come up as the first hit, but also add to the list three other covers of the song by artists you have never heard of, which you will find by scrolling down the search results page.

These versions exist because of something called a “compulsory license,” which means that by paying a defined fee to an agency, you are allowed to record a cover song without asking for, or receiving, permission from the artist who wrote it. The song becomes a recipe and you become the constructor.

Now visit a friend. Play the “Get Lucky” playlist on shuffle mode. When all four songs have been played, ask your friend to identify the original version. The guitar and bass and singing will sound surprisingly similar in each version. Your friend will probably ask, increasingly frantically: “Which is the one true song?”

Do not answer. Thank your friend, bow, and leave.

* * *

“Get Lucky” was co-written by Nile Rodgers, the mastermind behind some of the greatest pop music of the last 40 years, starting with Chic, the disco band that gave us infectious dance hits like “Good Times.” Shortly after “Good Times” was released as a single, the enterprising music producer Sylvia Robinson brought a funk band into a recording studio and had them copy Chic’s bassist Bernard Edwards’ memorable bass line from that song. She also sampled its string section. Adding some rappers no one had ever heard of before, she created “Rapper’s Delight,” which seemed laughable to those who really knew the inventive, emerging hip hop scene, but which rather effectively set rap music on a course for mainstream (and white) popularity.

Rodgers initially hated “Rapper’s Delight,” believing it was a wholesale copy of “Good Times,” and he and Edwards sued for copyright violation. Later, after he won and was listed as a co-writer of the song, he declared himself proud of “Rapper’s Delight.” He realized it was a brilliant theft that changed pop music forever, and yet didn’t diminish Chic’s original work.

“Rapper’s Delight” was far from the only hip hop song to borrow; in fact, the reuse of older recordings was standard within the new genre, and part of its enormous creativity. The technique reached its apogee in arguably the three seminal rap albums of the late 1980s: Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising, and Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique. Each of these albums had over a hundred samples, mixing and matching from different genres to make sounds that were totally new.

They were large, you nod, they contained multitudes.

* * *

In 1992, the science fiction author William Gibson, who had coined the word “cyberspace,” released a new work entitled Agrippa (A Book of the Dead). The text was issued, most famously, in a deluxe edition on a 3.5” floppy disk encased in an artisanally crafted box. The disk would encrypt itself upon a single reading, so you only had one shot to read the text as it scrolled across your screen.

This Agrippa cost $2000, and only a very small number were made. Gibson publicly revelled in the work’s combination of the ephemeral and the valuable. He loved that the book, after viewing, would become like a television tuned to a dead channel.

Almost immediately, however, the text of Agrippa was surreptitiously released on an underground electronic bulletin board called MindVox. Anyone can now read it online, and view the deluxe packaging as well.

What is the nature of art, you consider, without its packaging? What is its value?

* * *

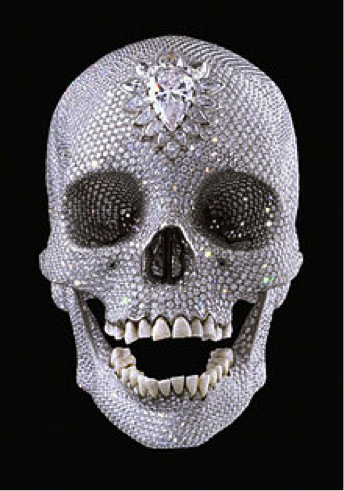

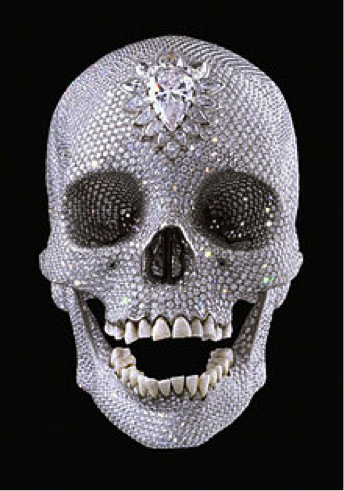

The British artist Damien Hirst is probably best known for putting a dead shark in a large tank of formaldehyde and giving it the existential title “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.” In 2007, he asked the jewelers who fabricate items for the British monarchy—scepters for the king—to make a human skull out of diamonds and platinum, based on a real skull he bought. The skull’s teeth were added to the final product. Hirst called this artwork “For the Love of God.” Many critics called it “tacky.”

But “For the Love of God” was as much an exercise in the finance that goes along with the contemporary art scene, where prices for works regularly head into eight or even nine figures at auction. The fabrication of the skull apparently cost £14 million, and Hirst tried to sell the bejeweled skull to bidders for £50 million. Although there were rumors of a sale, ultimately there were no takers. A mysterious consortium then evidently bought the skull, but for less than £50 million, perhaps much less, and oddly, Hirst seemed to be one of the investors. Some analysts believe that Hirst actually lost money on the deal.

Once Upon a Time in Shaolin was also rumored to be for sale for a much higher number, perhaps as much as $5 million, but Shkreli ultimately bought it for $2 million, which is far less than the Wu-Tang Clan would make from a regular album release.

* * *

What is Once Upon a Time in Shaolin really worth? Is its scarcity its worth, and its worth its true art and value?

Once Upon a Time in Shaolin may not be as scarce as we imagine. It surely exists beyond the sole copy in Martin Shkreli’s apartment. It exists in the sense that members of Wu-Tang created it and still have its music in their heads and could likely recreate it if they wanted. Perhaps RZA is humming some of the songs in his shower right now. It exists as a recipe.

But it may also exist in actuality, albeit in pieces, like the wisps of a cloud. The master recordings may have been destroyed, but the way that digital recording works mean that elements of Once existed more than once on magnetic media and probably, somewhere, continue to exist regardless of what Wu-Tang Clan has done with the completed master. Parts of the album can probably be dug up, like the scepter of an Egyptian king, or the disappearing poetry on a phosphorus screen.

If samples were used, they exist on other recordings; if a drum machine was used, those beats exist, identically, on many other machines. Any computers involved surely have files that have not been truly erased, and that could be dug up by digital archaeologists. There may be assembly to be done, and perhaps the final product would be different from the “original.” Or would it?

And perhaps too many traces of the full Once Upon a Time in Shaolin exist for it not to leak, just as Agrippa did.

Of course, then it will just be another stream of bits among the countless streams in our ephemeral era, severed from its unique packaging. It will take its place on millions of playlists, its songs sitting alongside tens of millions of other songs.

We will have gained something from Once’s liberation, but then we will have lost something as well.

* * *

The abstract artist Ellsworth Kelly, who recently died, was once asked about the nature of art. “I think what we all want from art is a sense of fixity, a sense of opposing the chaos of daily living,” he said, with more than a bit of Shaolin wisdom. “This is an illusion, of course.”