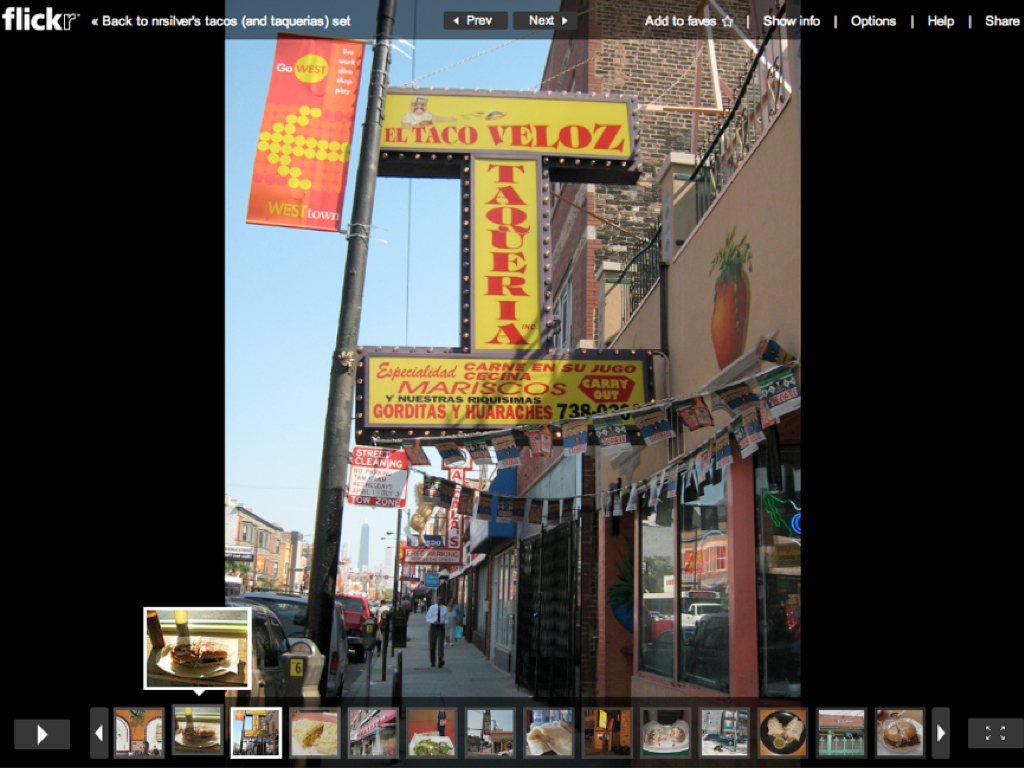

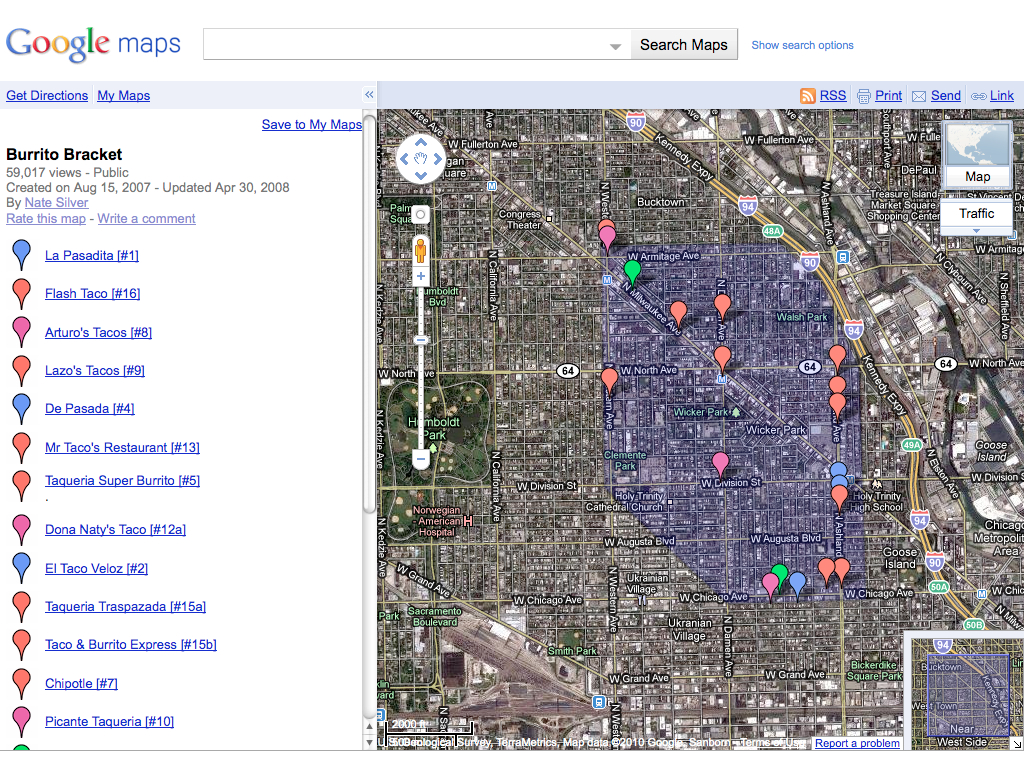

In the summer of 2007, Nate Silver decided to conduct a rigorous assessment of the inexpensive Mexican restaurants in his neighborhood, Chicago’s Wicker Park. Figuring that others might be interested in the results of his study, and that he might be able to use some feedback from an audience, he took his project online.

Silver had no prior experience in such an endeavor. By day he worked as a statistician and writer at Baseball Prospectus—an innovator, to be sure, having created a clever new standard for empirically measuring the value of players, an advanced form of the “sabermetrics” vividly described by Michael Lewis in Moneyball. ((Nate Silver, “Introducing PECOTA,” in Gary Huckabay, Chris Kahrl, Dave Pease et al., eds., Baseball Prospectus 2003 (Dulles, VA: Brassey’s Publishers, 2003): 507-514. Michael Lewis, Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004).)) But Silver had no experience as a food critic, nor as a web developer.

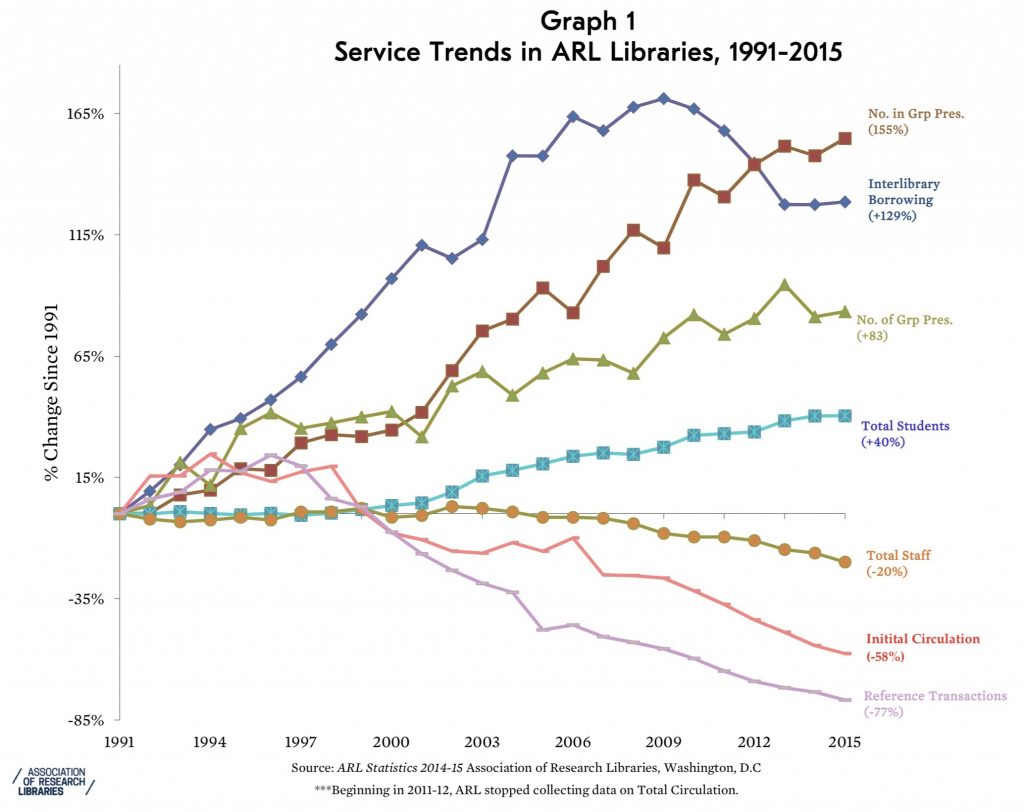

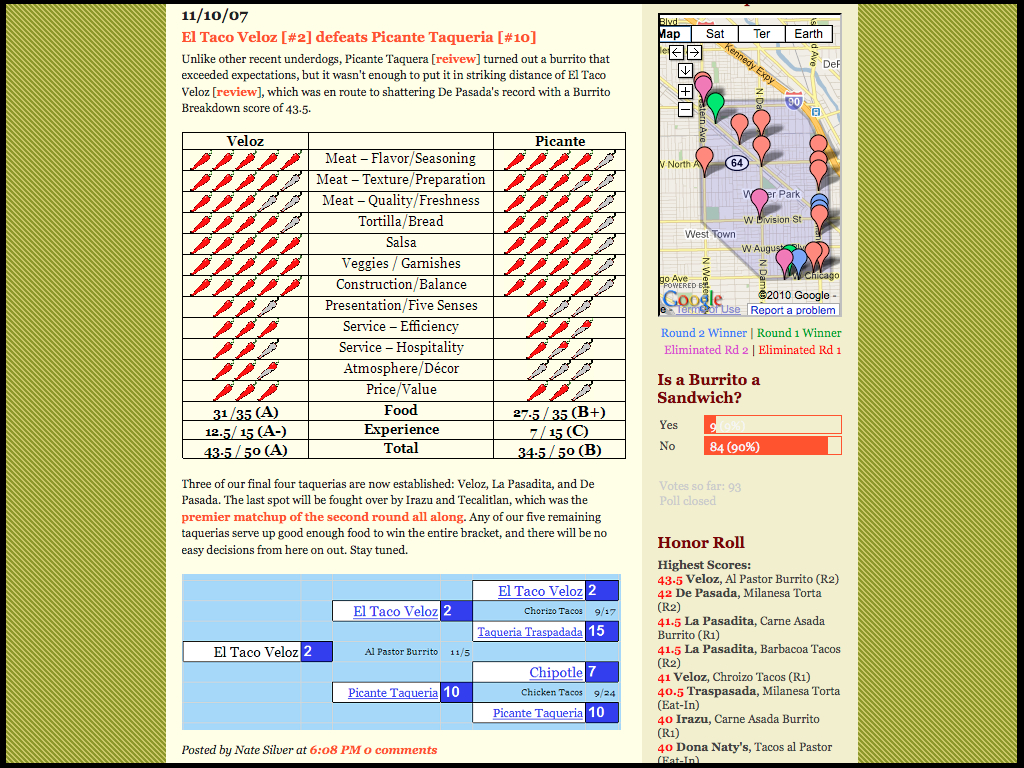

In time, his appetite took care of the former and the open web took care of the latter. Silver knit together a variety of free services as the tapestry for his culinary project. He set up a blog, The Burrito Bracket, using Google’s free Blogger web application. Weekly posts consisted of his visits to local restaurants, and the scores (in jalapeños) he awarded in twelve categories.

-

Home page of Nate Silver’s Burrito Bracket

-

Ranking system (upper left quadrant)

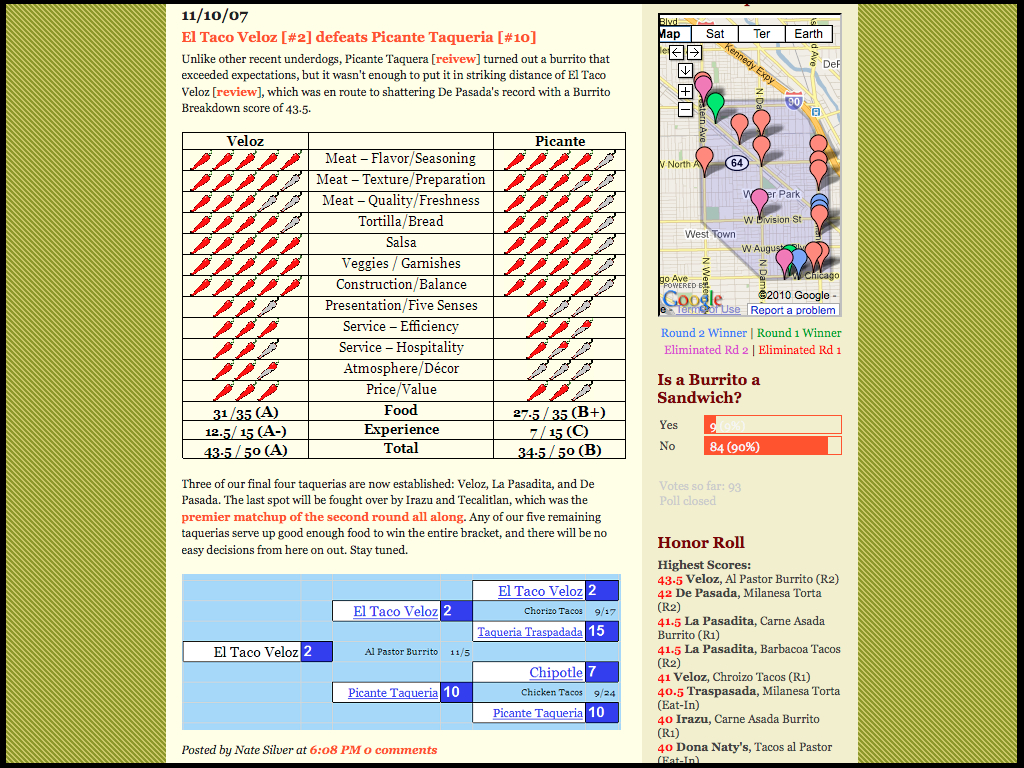

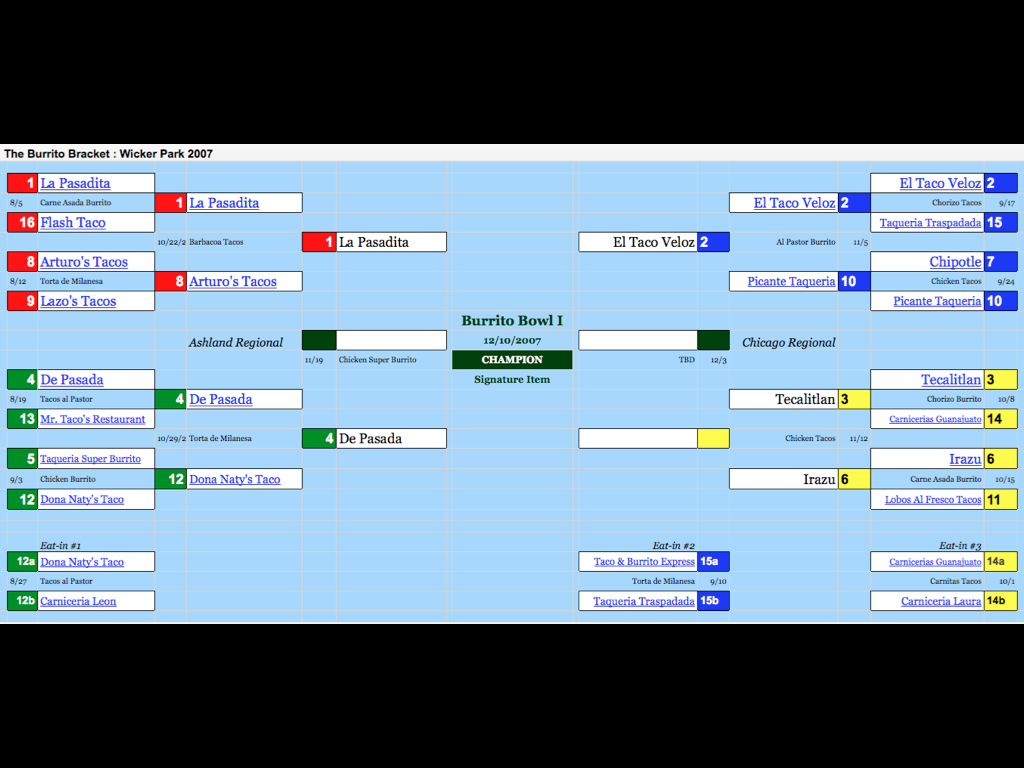

Being a sports geek, he organized the posts as a series of contests between two restaurants. Satisfying his urge to replicate March Madness, he modified another free application from Google, generally intended to create financial or data spreadsheets, to produce the “bracket” of the blog’s title.

-

Google Spreadsheets used to create the competition bracket

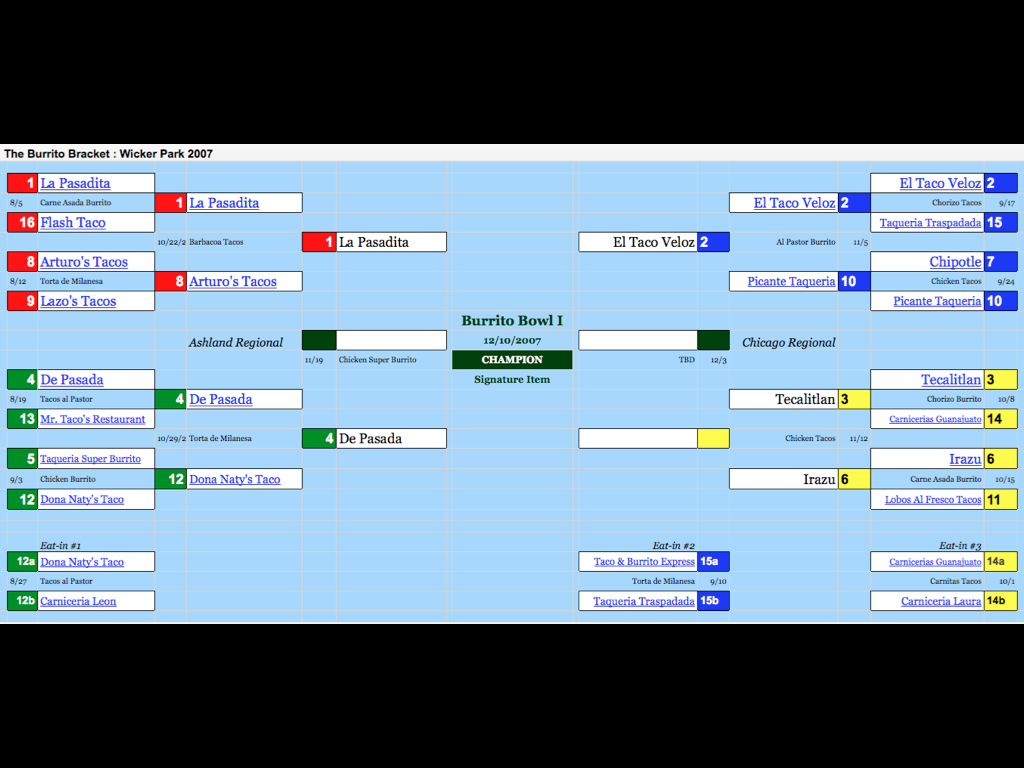

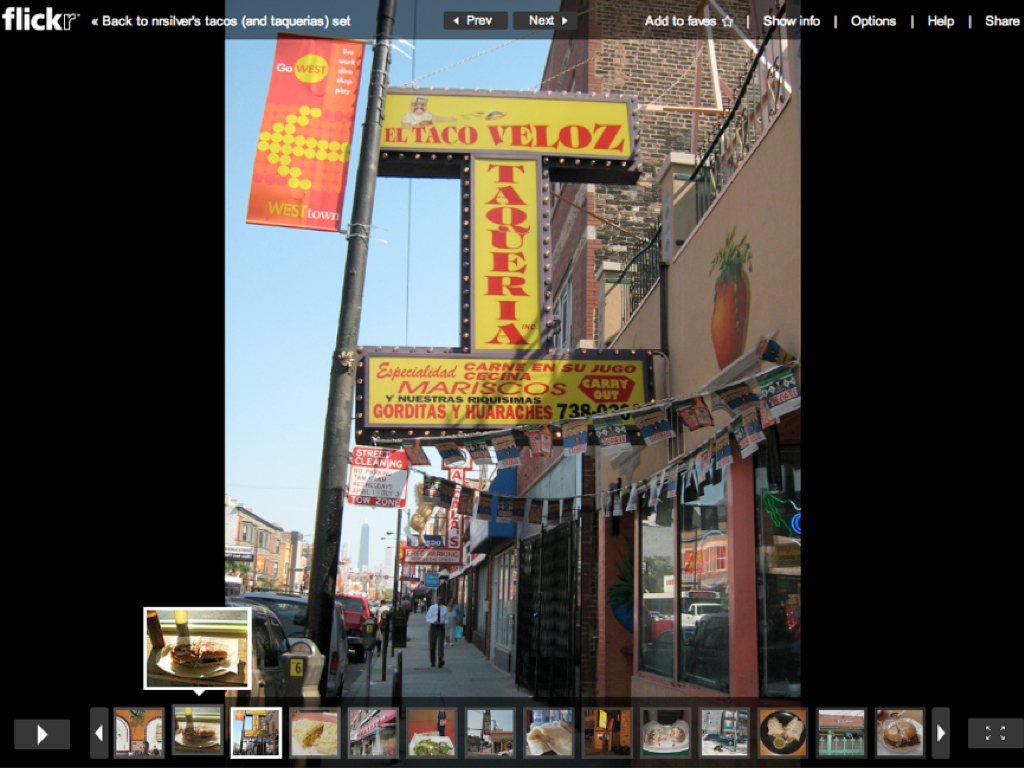

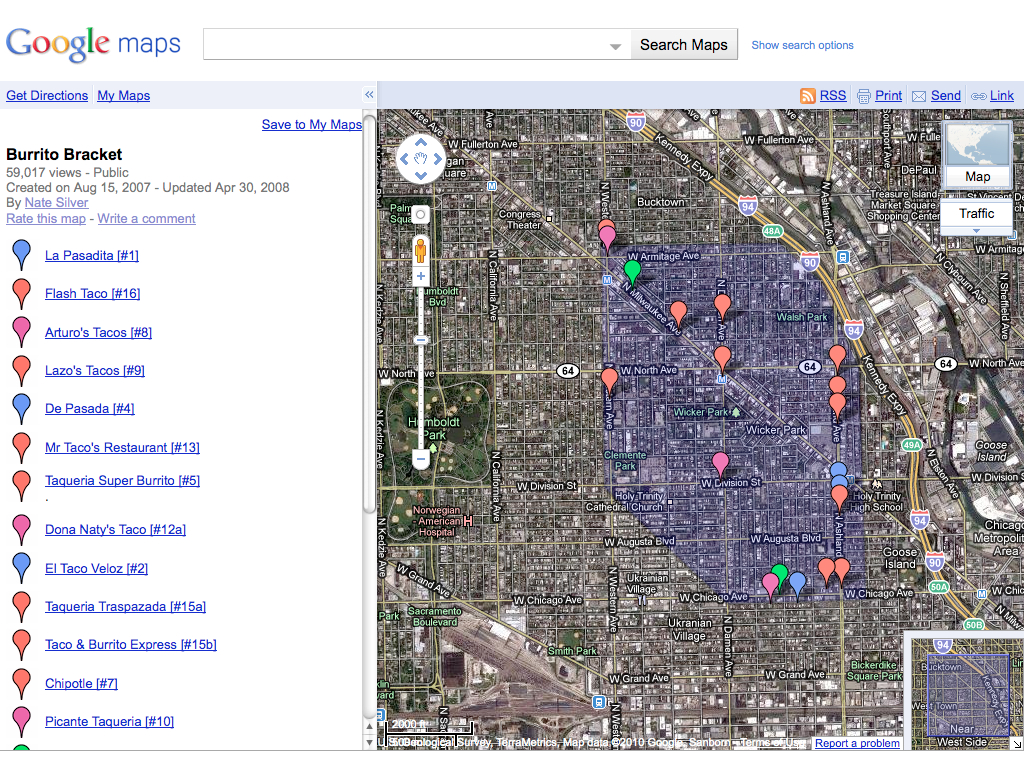

Like many of the savviest users of the web, Silver started small and improved the site as he went along. For instance, he had started to keep a photographic record of his restaurant visits and decided to share this documentary evidence. So he enlisted the photo-sharing site Flickr, creating an off-the-rack archive to accompany his textual descriptions and numerical scores. On August 15, 2007, he added a map to the site, geolocating each restaurant as he went along and color-coding the winners and losers.

-

Flickr photo archive for The Burrito Bracket (flickr.com)

-

Silver’s Google Map of Chicago’s Wicker Park (shaded in purple) with the location of each Mexican restaurant pinpointed

Even with its do-it-yourself enthusiasm and the allure of carne asada, Silver had trouble attracting an audience. He took to Yelp, a popular site for reviewing restaurants to plug The Burrito Bracket, and even thought about creating a Super Burrito Bracket, to cover all of Chicago. ((Frequently Asked Questions, The Burrito Bracket, http://burritobracket.blogspot.com/2007/07/faq.html)) But eventually he abandoned the site following the climactic “Burrito Bowl I.”

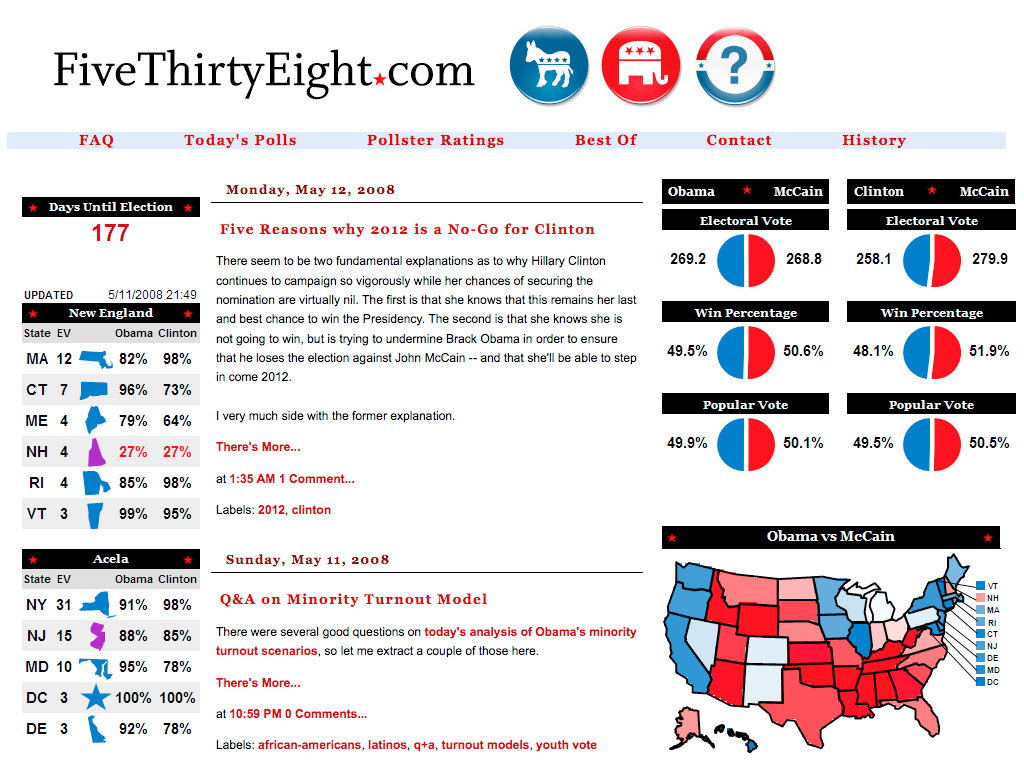

With his web skills improved and a presidential election year approaching, Silver decided to try his mathematical approach on that subject instead—”an opportunity for a sort of Moneyball approach to politics,” as he would later put it. ((http://www.journalism.columbia.edu/system/documents/477/original/nate_silver.pdf)) Initially, and with a nod to his obsession with Mexican food, he posted his empirical analyses of politics under the chili-pepper pseudonym “Poblano,” on the liberal website Daily Kos, which hosts blogs for its engaged readers.

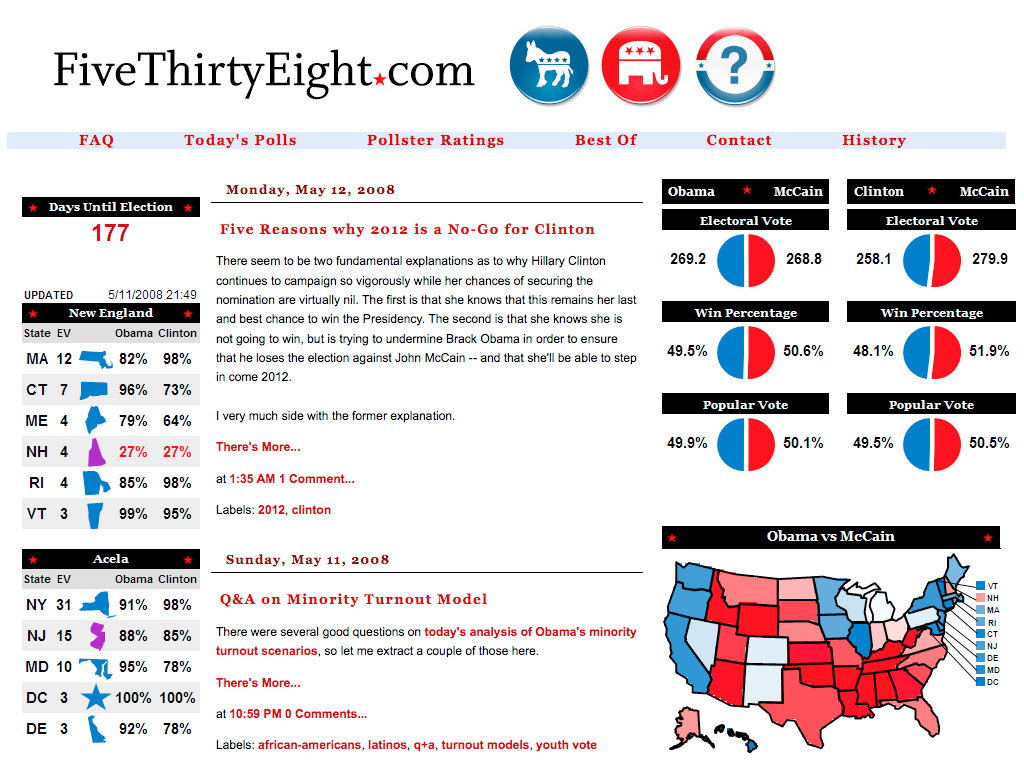

Then, in March 2008, Silver registered his own web domain, with a title that was simultaneously and appropriately mathematical and political: fivethirtyeight.com, a reference to the total number of electors in the United States electoral college. He launched the site with a slight one-paragraph post on a recent poll from South Dakota and a summary of other recent polling from around the nation. As with The Burrito Bracket it was a modest start, but one that was modular and extensible. Silver soon added maps and charts to bolster his text.

-

FiveThirtyEight two months after launch, in May 2008

Nate Silver’s real name and FiveThiryEight didn’t remain obscure for long. His mathematical modeling of the competition between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination proved strikingly, almost creepily, accurate. Clear-eyed, well-written, statistically rigorous posts began to be passed from browsers to BlackBerries, from bloggers to political junkies to Beltway insiders. From those wired early subscribers to his site, Silver found an increasingly large audience of those looking for data-driven, deeply researched analysis rather than the conventional reporting that presented political forecasting as more art than science.

FiveThiryEight went from just 800 visitors a day in its first month to a daily audience of 600,000 by October 2008. ((Adam Sternbergh, The Spreadsheet Psychic, New York, Oct 12, 2008, http://nymag.com/news/features/51170/)) On election day, FiveThiryEight received a remarkable 3

million

visitors, more than most daily newspapers

. ((http://www.journalism.columbia.edu/system/documents/477/original/nate_silver.pdf))

All of this attention for a site that most media coverage still called, with a hint of deprecation, a “blog,” or “aggregator” of polls, despite Silver’s rather obvious, if latent, journalistic skills. (Indeed, one of his roads not taken had been an offer, straight out of college, to become an assistant at The Washington Post. ((http://www.journalism.columbia.edu/system/documents/477/original/nate_silver.pdf)) ) An article in the Colorado Daily on the emergent genre represented by FiveThirtyEight led with Ken Bickers, professor and chair of the political science department at the University of Colorado, saying that such sites were a new form of “quality blogs” (rather than, evidently, the uniformly second-rate blogs that had previously existed). The article then swerved into much more ominous territory, asking whether reading FiveThirtyEight and similar blogs was potentially dangerous, especially compared to the safe environs of the traditional newspaper. Surely these sites were superficial, and they very well might have a negative effect on their audience:

Mary Coussons-Read, a professor of psychology at CU Denver, says today’s quick turnaround of information helps to make it more compelling.

“Information travels so much more quickly,” she says. “(We expect) instant gratification. If people have a question, they want an answer.”

That real-time quality can bring with it the illusion that it’s possible to perceive a whole reality by accessing various bits of information.

“There’s this immediacy of the transfer of information that leads people to believe they’re seeing everything … and that they have an understanding of the meaning of it all,” she says.

And, Coussons-Read adds, there is pleasure in processing information.

“I sometimes feel like it’s almost a recreational activity and less of an information-gathering activity,” she says.

Is it addiction?

[Michele] Wolf says there is something addicting about all that data.

“I do feel some kind of high getting new information and being able to process it,” she says. “I’m also a rock climber. I think there are some characteristics that are shared. My addiction just happens to be information.”

While there’s no such mental-health diagnosis as political addiction, Jeanne White, chemical dependency counselor at Centennial Peaks Hospital in Louisville, says political information seeking could be considered an addictive process if it reaches an extreme. ((Cindy Sutter, “Hooked on information: Can political news really be addicting?” The Colorado Daily, November 3, 2008, http://www.coloradodaily.com/ci_13105998))

This stereotype of blogs as the locus of “information” rather than knowledge, of “recreation” rather than education, was—and is—a common one, despite the wide variety of blogs, including many with long-form, erudite writing. Perhaps in 2008 such a characterization of FiveThirtyEight was unsurprising given that Silver’s only other credits to date were the Player Empirical Comparison and Optimization Test Algorithm (PECOTA) and The Burrito Bracket. Clearly, however, here was an intelligent researcher who had set his mind on a new topic to write about, with a fresh, insightful approach to the material. All he needed was a way to disseminate his findings. His audience appreciated his extraordinarily clever methods—at heart, academic techniques—for cutting through the mythologies and inadequacies of standard political commentary. All they needed was a web browser to find him.

A few journalists saw past the prevailing bias against non-traditional outlets like FiveThirtyEight. In the spring of 2010, Nate Silver bumped into Gerald Marzorati, the editor of the New York Times Magazine, on a train platform in Boston. They struck up a conversation, which eventually turned into a discussion about how FiveThirtyEight might fit into the universe of the Times, which ultimately recognized the excellence of his work and wanted FiveThirtyEight to enhance their political reporting and commentary. That summer, a little more than two years after he had started FiveThirtyEight, Silver’s “blog” merged into the Times under a licensing deal. ((Nate Silver, “FiveThirtyEight to Partner with New York Times, http://www.fivethirtyeight.com/2010/06/fivethirtyeight-to-partner-with-new.html)) In less time than it takes for most students to earn a journalism degree, Silver had willed himself into writing for one of the world’s premier news outlets, taking a seat in the top tier of political analysis. A radically democratic medium had enabled him to do all of this, without the permission of any gatekeeper.

-

FiveThirtyEight on the New York Times website, 2010

* * *

The story of Nate Silver and FiveThirtyEight has many important lessons for academia, all stemming from the affordances of the open web. His efforts show the do-it-yourself nature of much of the most innovative work on the web, and how one can iterate toward perfection rather than publishing works in fully polished states. His tale underlines the principle that good is good, and that the web is extraordinarily proficient at finding and disseminating the best work, often through continual, post-publication, recursive review. FiveThirtyEight also shows the power of openness to foster that dissemination and the dialogue between author and audience. Finally, the open web enables and rewards unexpected uses and genres.

Undoubtedly it is true that the path from The Burrito Bracket to The New York Times may only be navigated by an exceptionally capable and smart individual. But the tools for replicating Silver’s work are just as open to anyone, and just as powerful. It was with that belief, and the desire to encourage other academics to take advantage of the open web, that Roy Rosenzweig and I wrote Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web. ((Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).)) We knew that the web, although fifteen years old at the time, was still somewhat alien to many professors, graduate students, and even undergraduates (who might be proficient at texting but know nothing about HTML), and we wanted to make the medium more familiar and approachable.

What we did not anticipate was another kind of resistance to the web, based not on an unfamiliarity with the digital realm or on Luddism but on the remarkable inertia of traditional academic methods and genres—the more subtle and widespread biases that hinder the academy’s adoption of new media. These prejudices are less comical, and more deep-seated, than newspapers’ penchant for tales of internet addiction. This resistance has less to do with the tools of the web and more to do with the web’s culture. It was not enough for us to conclude Digital History by saying how wonderful the openness of the web was; for many academics, this openness was part of the problem, a sign that it might be like “playing tennis with the net down,” as my graduate school mentor worriedly wrote to me. ((http://www.dancohen.org/2010/11/11/frank-turner-on-the-future-of-peer-review/))

In some respects, this opposition to the maximal use of the web is understandable. Almost by definition, academics have gotten to where they are by playing a highly scripted game extremely well. That means understanding and following self-reinforcing rules for success. For instance, in history and the humanities at most universities in the United States, there is a vertically integrated industry of monographs, beginning with the dissertation in graduate school—a proto-monograph—followed by the revisions to that work and the publication of it as a book to get tenure, followed by a second book to reach full professor status. Although we are beginning to see a slight liberalization of rules surrounding dissertations—in some places dissertations could be a series of essays or have digital components—graduate students infer that they would best be served on the job market by a traditional, analog monograph.

We thus find ourselves in a situation, now more than two decades into the era of the web, where the use of the medium in academia is modest, at best. Most academic journals have moved online but simply mimic their print editions, providing PDF facsimiles for download and having none of the functionality common to websites, such as venues for discussion. They are also largely gated, resistant not only to access by the general public but also to the coin of the web realm: the link. Similarly, when the Association of American University Presses recently asked its members about their digital publishing strategies, the presses tellingly remained steadfast in their fixation on the monograph. All of the top responses were about print-on-demand and the electronic distribution and discovery of their list, with a mere footnote for a smattering of efforts to host “databases, wikis, or blogs.” ((Association of American University Presses, “Digital Publishing in the AAUP Community; Survey Report: Winter 2009-2010,” http://aaupnet.org/resources/reports/0910digitalsurvey.pdf, p. 2)) In other words, the AAUP members see themselves almost exclusively as book publishers, not as publishers of academic work in whatever form that may take. Surveys of faculty show comfort with decades-old software like word processors but an aversion to recent digital tools and methods. ((See, for example, Robert B. Townsend, “How Is New Media Reshaping the Work of Historians?”, Perspectives on History, November 2010, http://www.historians.org/Perspectives/issues/2010/1011/1011pro2.cfm)) The professoriate may be more liberal politically than the most latte-filled ZIP code in San Francisco, but we are an extraordinarily conservative bunch when in comes to the progression and presentation of our own work. We have done far less than we should have by this point in imagining and enacting what academic work and communication might look like if it was digital first.

To be sure, as William Gibson has famously proclaimed, “The future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.” ((National Public Radio, “Talk of the Nation” radio program, 30 November 1999, timecode 11:55, http://discover.npr.org/features/feature.jhtml?wfId=1067220)) Almost immediately following the advent of the web, which came out of the realm of physics, physicists began using the Los Alamos National Laboratory preprint server (later renamed ArXiv and moved to arXiv.org) to distribute scholarship directly to each other. Blogging has taken hold in some precincts of the academy, such as law and economics, and many in those disciplines rely on web-only outlets such as the Social Science Research Network. The future has had more trouble reaching the humanities, and perhaps this book is aimed slightly more at that side of campus than the science quad. But even among the early adopters, a conservatism reigns. For instance, one of the most prominent academic bloggers, the economist Tyler Cowen, still recommends to students a very traditional path for their own work. ((“Tyler Cowen: Academic Publishing,” remarks at the Institute for Humane Studies Summer Research Fellowship weekend seminar, May 2011, http://vimeo.com/24124436)) And far from being preferred by a large majority of faculty, quests to open scholarship to the general public often meet with skepticism. ((Open access mandates have been tough sells on many campuses, passing only by slight majorities or failing entirely. For instance, such a mandate was voted down at the University of Maryland, with evidence of confusion and ambivalence. http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2009/04/28/umaryland-faculty-vote-no-oa/))

If Digital History was about the mechanisms for moving academic work online, this book is about how the digital-first culture of the web might become more widespread and acceptable to the professoriate and their students. It is, by necessity, slightly more polemical than Digital History, since it takes direct aim at the conservatism of the academy that twenty years of the web have laid bare. But the web and the academy are not doomed to an inevitable clash of cultures. Viewed properly, the open web is perfectly in line with the fundamental academic goals of research, sharing of knowledge, and meritocracy. This book—and it is a book rather than a blog or stream of tweets because pragmatically that is the best way to reach its intended audience of the hesitant rather than preaching to the online choir—looks at several core academic values and asks how we can best pursue them in a digital age.

First, it points to the critical academic ability to look at any genre without bias and asks whether we might be violating that principle with respect to the web. Upon reflection many of the best things we discover in scholarship are found by disregarding popularity and packaging, by approaching creative works without prejudice. We wouldn’t think much of the meandering novel Moby-Dick if Carl Van Doren hadn’t looked past decades of mixed reviews to find the genius in Melville’s writing. Art historians have similarly unearthed talented artists who did their work outside of the royal academies and the prominent schools of practice. As the unpretentious wine writer Alexis Lichine shrewdly said in the face of fancy labels and appeals to mythical “terroir”: “There is no substitute for pulling corks.” ((Quoted in Frank J. Prial, “Wine Talk,” New York Times, 17 August 1994, http://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/17/garden/wine-talk-983519.html.))

Good is good, no matter the venue of publication or what the crowd thinks. Scholars surely understand that on a deep level, yet many persist in the valuing venue and medium over the content itself. This is especially true at crucial moments, such as promotion and tenure. Surely we can reorient ourselves to our true core value—to honor creativity and quality—which will still guide us to many traditionally published works but will also allow us to consider works in some nontraditional venues such as new open access journals or articles written and posted on a personal website or institutional repository, or digital projects.

The genre of the blog has been especially cursed by this lack of open-mindedness from the academy. Chapter 1, “What is a Blog?”, looks at the history of the blog and blogging, the anatomy and culture of a genre that is in many ways most representative of the open web. Saddled with an early characterization as being the locus of inane, narcissistic writing, the blog has had trouble making real inroads in academia, even though it is an extraordinarily flexible form and the perfect venue for a great deal of academic work. The chapter highlights some of the best examples of academic blogging and how they shape and advance arguments in a field. We can be more creative in thinking about the role of the blog within the academy, as a venue for communicating our work to colleagues as well as to a lay audience beyond the ivory tower.

This academic prejudice against the blog extends to other genres that have proliferated on the open web. Chapter 2, “Genres and the Open Web,” examines the incredible variety of those new forms, and how, with a careful eye, we might be able to import some of them profitably into the academy. Some of these genres, like the wiki, are well-known (thanks to Wikipedia, which academics have come to accept begrudgingly in the last five years). Other genres are rarer but take maximal advantage of the latitude of the open web: its malleability and interactivity. Rather than imposing the genres we know on the web—as we do when we post PDFs of print-first journal articles—we would do well to understand and adopt the web’s native genres, where helpful to scholarly pursuits.

But what of our academic interest in validity and excellence, enshrined in our peer review system? Chapter 3, “Good is Good,” examines the fundamental requirements of any such system: the necessity of highlighting only a minority of the total scholarly output, based on community standards, and of disseminating that minority of work to communities of thought and practice. The chapter compares print-age forms of vetting with native web forms of assessment and review, and proposes ways that digital methods can supplement—or even replace—our traditional modes of peer review.

“The Value, and Values, of Openness,” Chapter 4, broadly examines the nature of the web’s openness. Oddly, this openness is both the easiest trait of the web to understand and its most complex, once one begins to dig deeper. The web’s radical openness not only has led to calls for open access to academic work, which has complicated the traditional models of scholarly publishers and societies; it has also challenged our academic predisposition toward perfectionism—the desire to only publish in a “final” format, purged (as much as possible) of error. Critically, openness has also engendered unexpected uses of online materials—for instance, when Nate Silver refactored poll numbers from the raw data polling agencies posted.

Ultimately, openness is at the core of any academic model that can operate effectively on the web: it provides a way to disseminate our work easily, to assess what has been published, and to point to what’s good and valuable. Openness can naturally lead—indeed, is leading—to a fully functional shadow academic system for scholarly research and communication that exists beyond the more restrictive and inflexible structures of the past.