An increasing array of cutting-edge, often computationally intensive methods can now reveal formerly hidden texts, images, and material culture from centuries ago, and make those documents available for search, discovery, and analysis. Note how in the following four case studies, the emphasis is on the human; the futuristic technology is remarkable, but it is squarely focused on helping us understand human culture better.

Gothic Lasers

If you look very closely, you can see that the stone ribs in these two vaults in Wells Cathedral are slightly different, even though they were supposed to be identical. Alexandrina Buchanan and Nicholas Webb noticed this too and wanted to know what it said about the creativity and input of the craftsmen into the design: how much latitude did they have to vary elements from the architectural plans, when were those decisions made, and by whom? Before construction or during it, or even on the spur of the moment, as the ribs were carved and converged on the ceiling? How can we recapture a decent sense of how people worked and thought from inert physical objects? What was the balance between the pursuit of idealized forms, and practical, seat-of-the-pants tinkering?

In “Creativity in Three Dimensions: An Investigation of the Presbytery Aisles of Wells Cathedral,” they decided to find out by measuring each piece of stone much more carefully than can be done with the human eye. Prior scholarship on the cathedral—and the question of the creative latitude and ability of medieval stone craftsmen—had used 2-D drawings, which were not granular enough to reveal how each piece of the cathedral was shaped by hand to fit, or to slightly shape-shift, into the final pattern. High-resolution 3-D scans using a laser revealed so much more about the cathedral—and those who constructed it, because individual decisions and their sequence became far clearer.

Although the article gets technical at moments (both with respect to the 3-D laser and computer modeling process, and with respect to medieval philosophy and architectural terms), it’s worth reading to see how Buchanan and Webb reach their affirming, humanistic conclusion:

The geometrical experimentation involved was largely contingent on measurements derived from the existing structure and the Wells vaults show no interest in ideal forms (except, perhaps in the five-point arches). We have so far found no evidence of so-called “Platonic” geometry, nor use of proportional formulae such as the ad quadratum and ad triangulatum principles. Use of the “four known elements” rule evidenced masons’ “cunning”, but did not involve anything more than manipulation and measurement using dividers rather than a calibrated ruler and none of the processes used required even the simplest mathematics. The designs and plans are based on practical ingenuity rather than theoretical knowledge.

Hard OCR

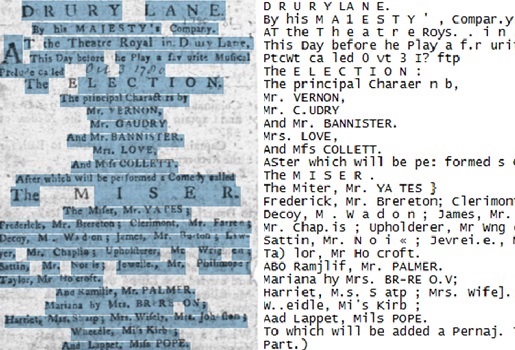

Last year at the Northeastern University Library we hosted a meeting on “hard OCR”—that is, physical texts that are currently very difficult to convert into digital texts using optical character recognition (OCR), a process that involves rapidly improving techniques like computer vision and machine learning. Representatives from libraries and archives, technology companies that have emerging AI tech (such as Google), and scholars with deep subject and language expertise all gathered to talk about how we could make progress in this area. (This meeting and the overall project by Ryan Cordell and David Smith of Northeastern’s NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks, “A Research Agenda for Historical and Multilingual Optical Character Recognition,” was generously funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.)

OCRing modern printed books has become if not a solved problem at least incredibly good—the best OCR software gets a character right in these textual conversions 99% of the time. But older printed books, ancient and medieval written works, writing outside of the Romance languages (e.g., in Arabic, Sanskrit, or Chinese), rare languages (such as Cherokee, with its unique 85-character alphabet, which I covered on the What’s New podcast), and handwritten documents of any kind, remain extremely challenging, with success rates often below 80%, and in some cases as low as 40%. That means 1-3 characters are mistakenly translated by the computer in a five-character word. Not good at all.

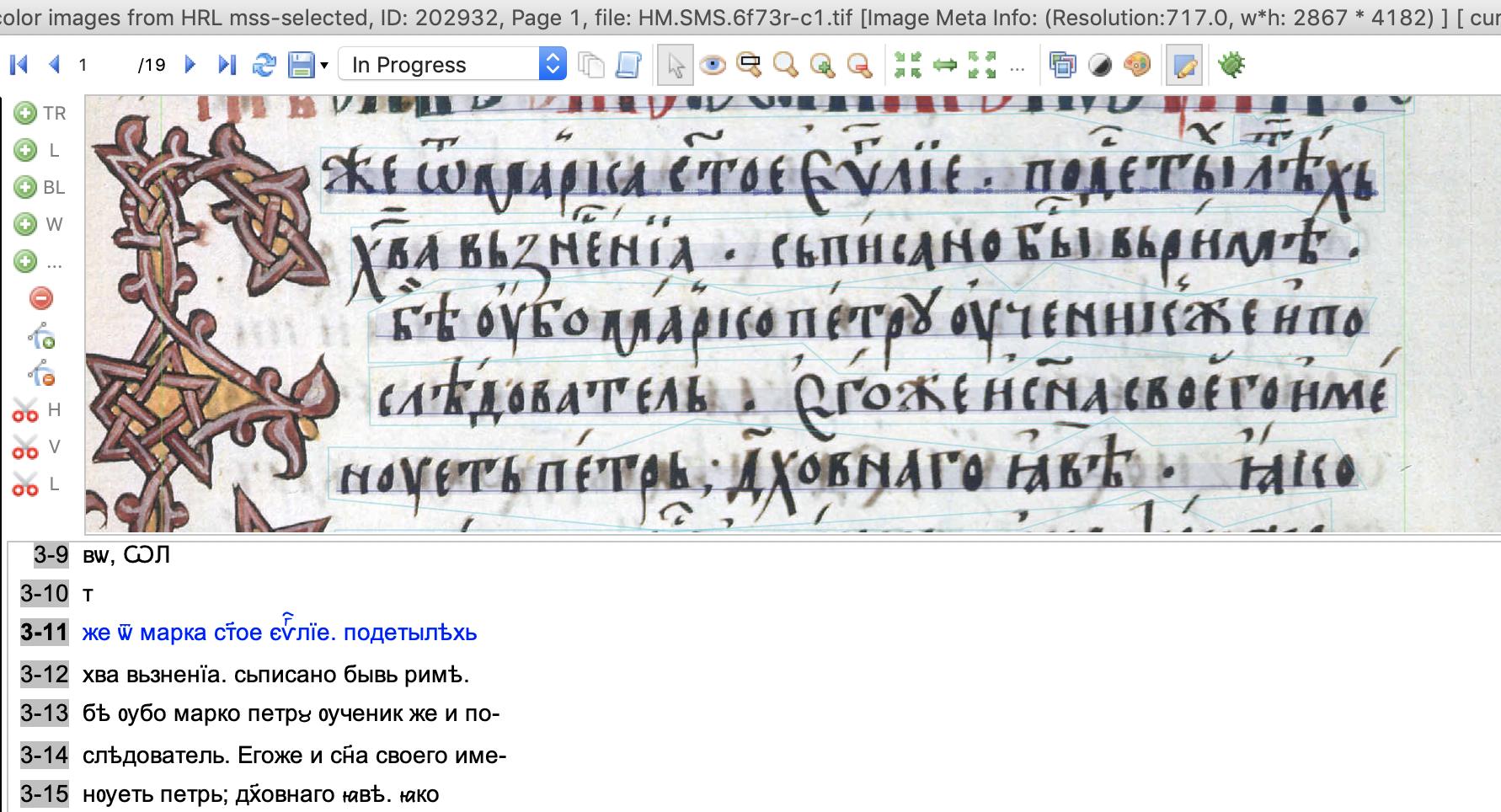

The meeting began to imagine a promising union of language expertise from scholars in the humanities and the most advanced technology for “reading” digital images. If the computer (which in the modern case, really means an immensely powerful cloud of thousands of computers) has some ground-truth texts to work from—say, a few thousand documents in their original form and a parallel machine-readable version of those same texts, painstakingly created by a subject/language expert—then a machine-learning algorithm can be created to interpret with much greater accuracy new texts in that language or from that era. In other words, if you have 10,000 medieval manuscript pages perfectly rendered in XML, you can train a computer to give you a reasonably effective OCR tool for the next 1,000,000 pages.

Transkribus is one of the tools that works in just this fashion, and it has been used to transcribe 1,000 years of highly variant written works, in many languages, into machine-readable text. Thanks to the monks of the Hilandar Monastery, who kindly shared their medieval manuscripts, Quinn Dombrowski, a digital humanities scholar with a specialty in medieval Slavic texts, trained Transkribus in handwritten Cyrillic manuscripts, and calls the latest results from the tool “truly nothing short of miraculous.”

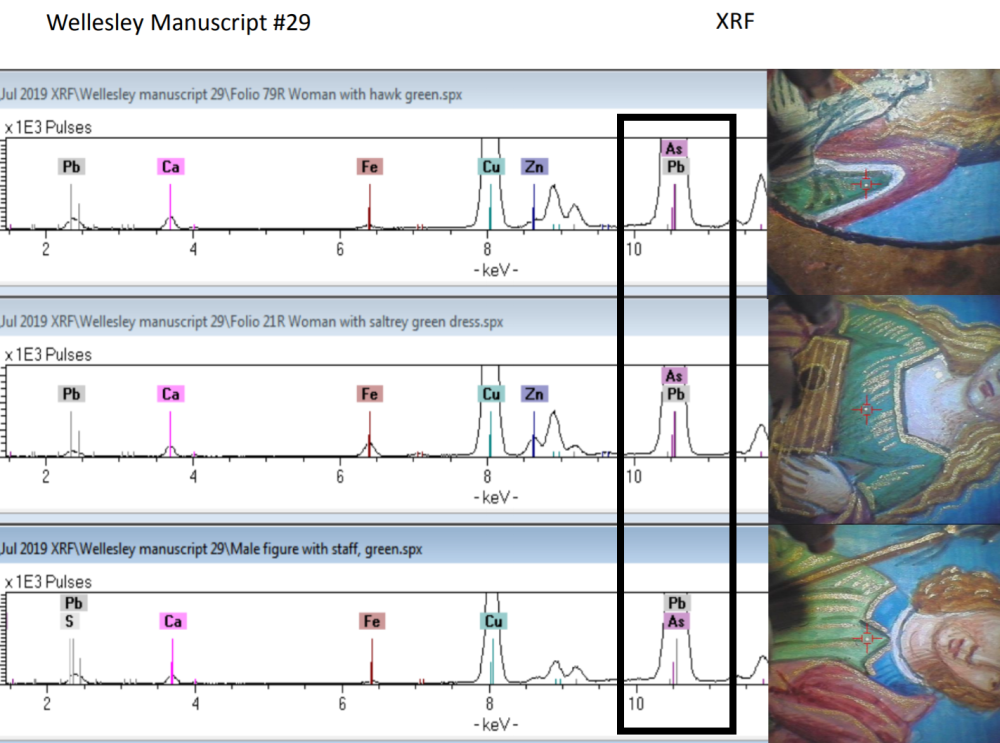

X-Manuscripts

Lisa Davis Fagin is the Executive Director of the Medieval Academy of America and her excellent blog, Manuscript Road Trip, is highly recommended. In a recent post, she explores the helpful use of X-ray florescence on an unusual Book of Hours.

It’s interesting to see the interplay between the intuition of scholars—this looks off in some way—and the data generated by the scientific instruments. Of course, things are not what they appear.

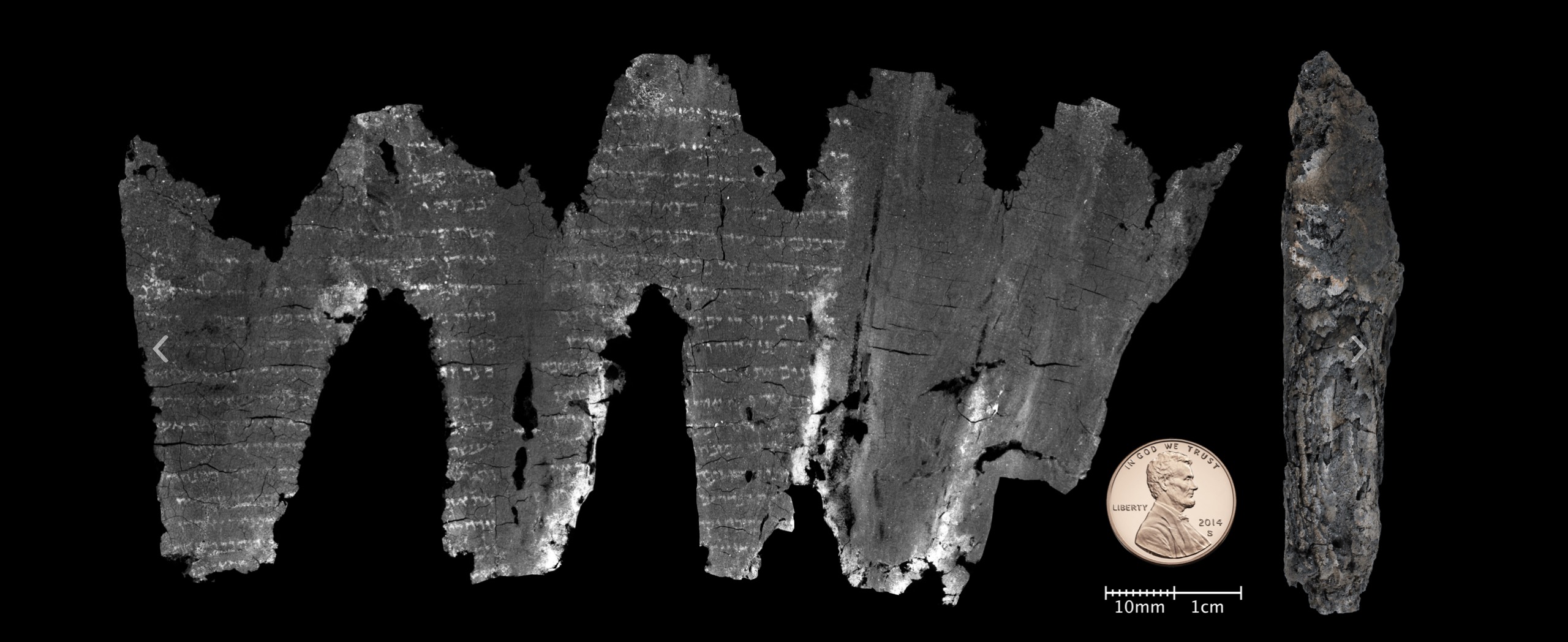

Really Hard OCR

Imagine trying to read an ancient text that was written in black ink on a scroll that was then roasted to a uniform, black crisp, and made so brittle it can never be unrolled. That’s what happened when Mount Vesuvius dumped twenty meters of lava on Herculaneum and flash-charred their libraries. These scrolls contain huge amounts of text that scholars are eager to read and that would undoubtedly greatly expand our understanding of ancient Rome and the Mediterranean region. But again: these texts look like the worst burnt burrito you’ve ever seen.

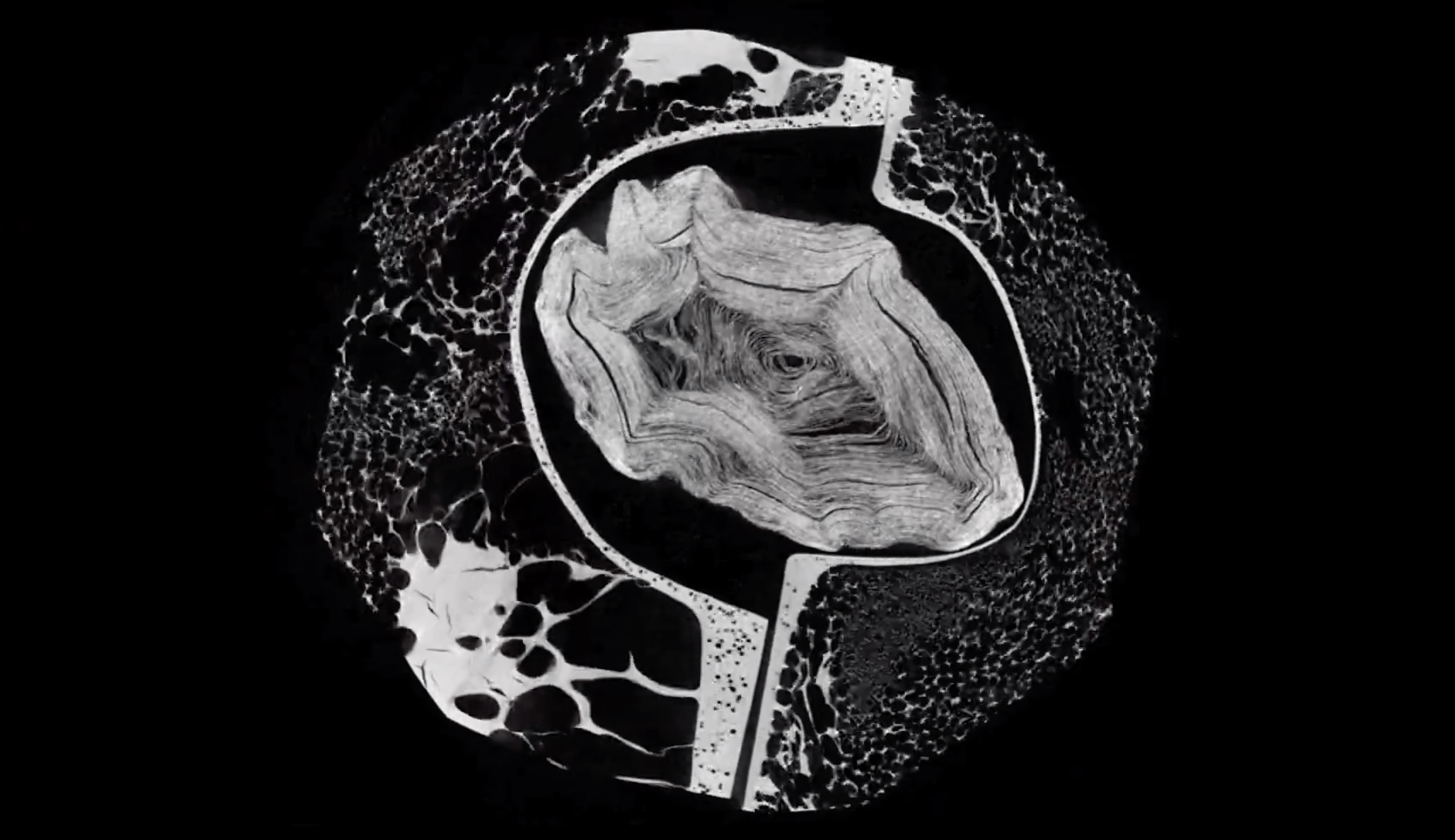

Enter the Digital Restoration Initiative, which has been developing a way to scan and virtually unwrap these blackened scrolls, and then extract the text from them so we can read what people wrote two thousand years ago. They pioneered this technique on the En-Gedi scroll (shown to the right of the penny, below) to computationally produce a flattened, readable text (to the left of the penny).

DRI is now working on the Herculaneum scrolls, and you can watch their techniques and tools, and the sheer complexity of the process, in this recent video:

These ancient texts, encased in a protective layer of hardened lava, look not unlike femurs, and their sectional scans really look like a CAT scan of a human bone. And that’s kind of beautiful, no?