This past weekend’s TEDxNYED event in New York took place in the theater of a school just off Broadway. I couldn’t help thinking about the symbolism of that location during the day’s proceedings. TEDx, a spinoff regional program of the billionaires-and-brains edutainment summit in California, TED, pushes speakers like me towards theatrics.

TEDxNYED was enjoyable and I greatly appreciated the opportunity to rub elbows with some digital luminaries and some very smart educators who are doing all the hard work in the trenches while I sit here in the ivory tower blogging. Whatever criticisms may be leveled, TEDxNYED was incredibly well-run and engaging. Before you read my thoughts below, you should first read the wrap-up from Dave Bill, the TEDxNYED “curator,” who gets it exactly right. I’m enormously appreciative of Dave’s hard work and the hard work of his TEDxNYED colleagues.

Back to Broadway: among other things, TEDxNYED gave me a chance to think more about the academic lecture as theater. (It also gave me a welcome chance to summon the vaudevillian genes of my New York Jewish heritage, the effectiveness of which you will be able to assess when the video is posted to the TEDx channel on YouTube in a couple of weeks.)

Take Larry Lessig, the de facto headliner of TEDxNYED. He’s clearly a first-rate legal scholar and influential activist. But after viewing him live, I realized more than ever that he’s also a rather talented performance artist, with crack comedic timing. (Here’s his talk; judge for yourself.)

We professors don’t like to admit it, but comedy and performance are important ingredients in most successful academic lectures, and can spur the pursuit of knowledge and action far better than serious monograph or article. When I was in college nearly everyone interested in history—from any era or place—took Stephen Cohen’s class on Soviet history, mostly because he was entertaining. He even had one lecture consisting entirely of jokes. Sure, it was gimmicky. But I also know several of my classmates who went into careers in diplomacy and history because of the inspiration.

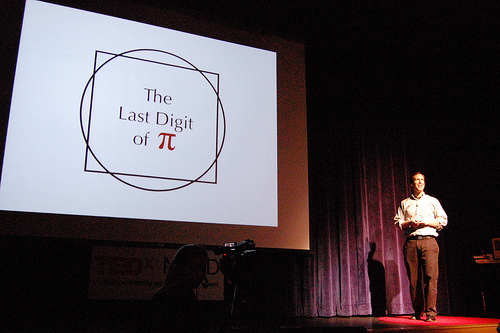

Of course, academic theater can also lead to problems. TED talks are limited to 18 minutes, inevitably leading to reductionism. As I quipped in my talk on the 6,000 year history of π, “Portions have been condensed.” The humanities particularly suffer from this condensation. For instance, as hugely entertaining as Lessig’s talk was, if you watch it I’m sure you’ll pick up that it conflates, quite problematically, two kinds of conservatism: religious conservatism and libertarianism. Just because the Cato Institute can imagine a role for remixes doesn’t mean that those who attend free church potlucks can. Modern conservatism is an extraordinarily complex mix; one need only look at the tension between libertarian and evangelical views of homosexuality. Gina Bianchini, the CEO of Ning, a network of social networks, presented her work as “the joy of connecting optimists from around the world,” leaving out the fact that the history of Ning is far more interesting: it started out as an engine for making web apps, only later turning toward social networking. That’s actually a fascinating, complex business history that I would have liked to hear more about.

TED’s tagline is the catchy “Ideas Worth Spreading.” I’m an intellectual historian and appreciate the emphasis on ideas; as an educator I’m in favor of spreading knowledge. But in my later years I’ve also come to realize that while ideas are important, execution is probably more important. Lessig and Bianchini also know this—Lessig is now working on methods of more effective lobbying and Bianchini is obviously a talented CEO—and it would have helped TEDxNYED if they had explained to the audience the nitty-gritty details of making real change and progress. It doesn’t come from clever sound bites.

The TED spotlight-on-the-stage format also encourages the audience to perceive the speakers as isolated geniuses, coming out to impart wisdom. The host who introduced me credited me as being the solitary creator of several projects and works, all of which were actually broad collaborations. Again, collaboration is more complex than the format allows. Jeff Jarvis decided to blow up the format by getting up on stage with the lights on and ranting about the insanities and inanities of modern education. This was effective in a Lenny Bruce sort of way, but like Bruce, it was the exception that proved the rule that we speakers were bound to a certain form of academic theater. Inspired by Jarvis, I broke the fourth wall and interacted with the audience a couple of times during my talk, but it was perhaps a little superficial.

Regardless of these criticisms—which I give, again, entirely in recognition of the success of the event and with an eye toward improvement for next year—I enjoyed the challenge of doing a TED talk. I’m working on a much more formal Big Lecture at Cambridge University, and TEDxNYED helpfully made me think about the problems with that format as well. Indeed, I’m not blaming TED for the problems of academic theater. I actually believe the fault lies with academics themselves, who have ceded the ground of public intellectualism in the past generation or two, leaving a vacuum that TED and TEDx are happy to fill.

Hopefully—and judging by the tweets and blog posts this is true—the attendees took away more of the advantages than the disadvantages of the format, and will go on from thought to action.

[photo credit: Kevin Jarrett]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.