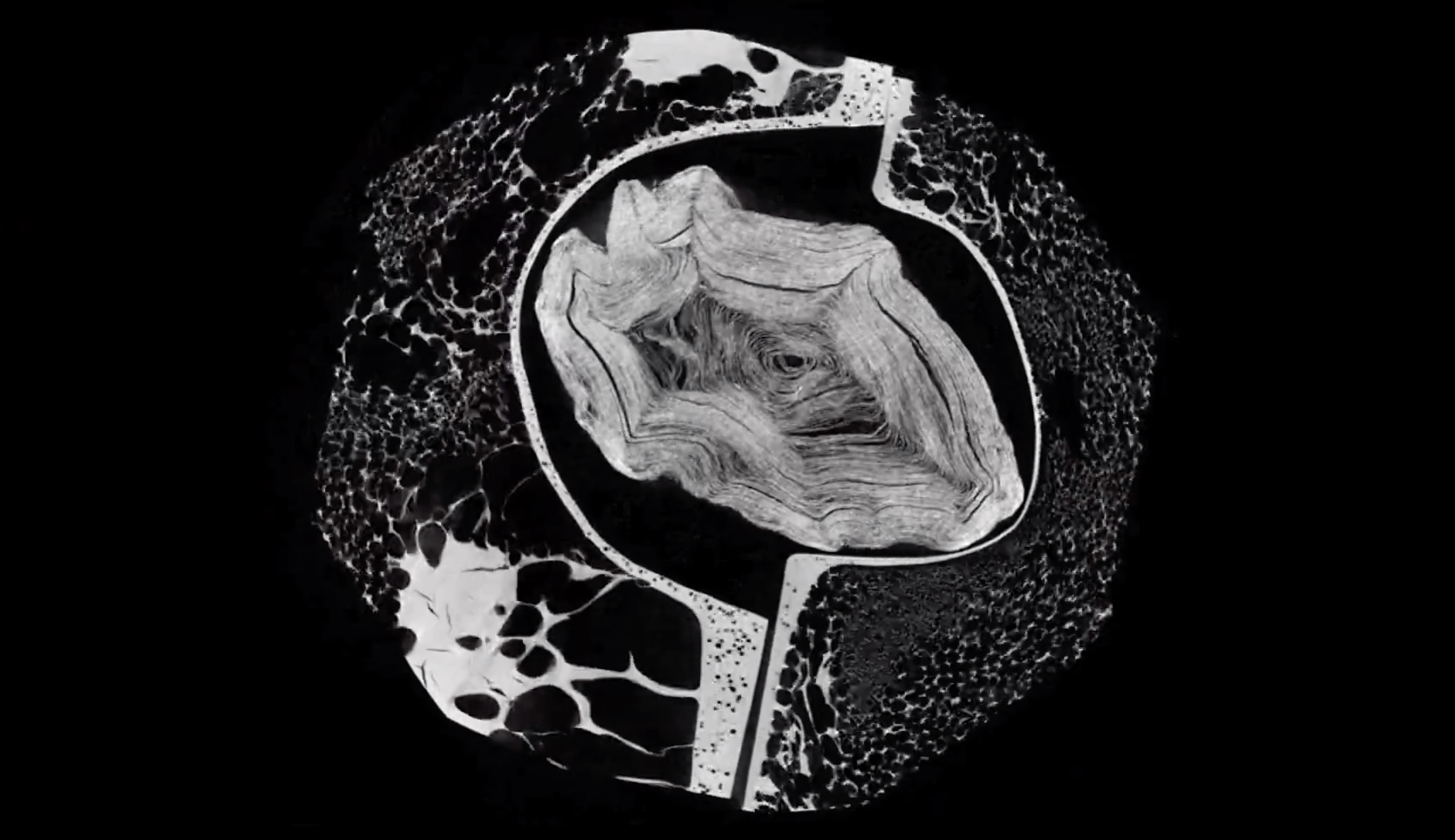

[3D-printed zoetrope from The National Science and Media Museum’s Wonderlab, via Sheryl Jenkins]

Modeling Humane Features

If it wasn’t a famous catchphrase coined by a young social media billionaire, and etched onto the walls of Facebook’s headquarters, the most likely place for “Move fast and break things” to appear would be on a mall-store t-shirt for faux skate punks. But even though Facebook has purportedly moved on from Mark Zuckerberg’s easily mocked motto, it is an ideology that remains widely in use, and that also engenders easy counter-takes, with some variation on “Move slowly and fix things.”

In a newsletter that seeks the contours of humane technology, moving slowly and fixing things seems like an obvious starting point, but it’s not enough and has the potential to be its own vapid motto unless we do a better job spelling out what it actually means. We need some examples, some modeling of how one goes about creating digital media that is Not Facebook. And for that we should revisit my emphasis in HI2on considering the psychology of humans before creating digital technology, and then again, constantly, during its implementation and growth.

In the signature block of this newsletter, you may have noticed that my preferred social media platform is Micro.blog, which I decamped to from Twitter last year in an attempt to cleanse my mind and streamline my online presence. (I am, however, still unclean; I have chosen to syndicate my Micro.blog posts to Twitter, since I still have many friends over there who wish to hear from me.) A big part of what I like about Micro.blog is that moving deliberately and considering things is deeply valued by Manton Reece, the architect of the platform, as well as his colleagues Jean MacDonald and Jonathan Hays.

Manton is admirably transparent and thoughtful about how he is designing and iterating on the platform (so much so that he’s writing a book about it, which surely makes him the most academic of app-makers). Even before Micro.blog’s launch, Manton thought through, and just as important, stuck to, key features—or non-features—such as no follower or like counts, anywhere, ever. (On Micro.blog you can see who people follow, to find others to follow yourself, but not how many people follow you or anyone else.) As Micro.blog has developed, Manton has also consulted with the burgeoning community about new features, to ensure that what he’s doing won’t disrupt the considerate, but still engaging, vibe of the place.

I have much more to say about Micro.blog, including some thoughts about its size, sustainability plan, and approach to hosting and personal data, but for this issue of HI I want to focus on a good case study of ethical technological implementation—a happy accident that turned into a valued (non-)feature. Last year an unintended update to the Micro.blog code suddenly made it impossible for users to see if someone was following them by clicking on their follows list. This seemed odd and in need of a fix, until everyone swiftly realized what a relaxing plus this is in today’s social media. The long thread of this revelation reads like a morality play; here’s a brief excerpt:

@jack: Either no one follows me here or the following list doesn’t include the user looking at the list. This has the effect of hiding whether or not someone follows me. If that’s the case, it’s genius.

@macgenie: @jack I had not realized that we don’t show whether someone is following you when you look at their Following list! That makes sense. / @manton

@jack: @macgenie I think it’s terrific. Avoids the awkwardness around any implied obligation for mutual follows :).

@manton: @macgenie @jack So… this is actually a bug that I introduced last night. But now I’m wondering if it’s a good thing! It’s confusing right now but maybe an opportunity to rethink this feature.

@jamesgowans: @manton I like it. It relieves the worry about whether someone follows you or doesn’t (a useless popularity metric), and places more value in replies/conversations. It’s sort of “all-in” on the no follower count philosophy.

@ayjay: @manton As the theologians say, O felix insectum!

Two weeks ago Rob Walker had a piece revisiting “Move fast and break things” and urging Silicon Valley to have an overriding focus on designing apps with bad actors in mind, for the worst of humanity who might seek to exploit an app for their own gain and to disrupt society. This should undoubtedly be an important aspect of digital design, especially so given what has happened online in the last few years.

But while architects should surely design an office building to thwart arsonists, they need to spend even more time designing spaces for those who are trying to work peacefully and productively within the building. Ultimately, we have to design platforms to withstand not only the worst of us, but the worst aspects of the rest of us. In thinking about seemingly small elements like whether you can see if someone is following you, Micro.blog’s Manton, Jean, and Jonathan get this critical point.

Teaching a Robot to Crack a Whip

In Robin Sloan’s novel Sourdough, the protagonist tries to teach a robot arm how to delicately and effectively crack an egg for cooking. This week on the What’s New podcast from the Northeastern University Library, I spoke to Dagmar Sternad from the Action Lab, who is, among other things, teaching a robot how to crack a whip. (She said that’s a very hard problem, especially to hit a particular point in space with the tip of the whip, but that egg cracking is a very, very hard problem.)

The Action Lab studies the complete range and technique of human motion very closely using the same technology Hollywood uses to create CGI characters—my favorite Action Lab case study looks at how ballet dancers in a duet transmit information through their fingertips to their partners—and then they encode that knowledge into digital and then robotic surrogates through biomimetics.

[Dagmar Sternad with two ballet dancers and a robot arm]

What I also found interesting about Dagmar’s work, and very germane to what I’m trying to do in this newsletter, is the bidirectionality of learning between humans and machines. You will be glad to hear that the Action Lab is not seeking to create whip-cracking robots of doom. But by observing humans doing intricate tasks, and then replicating those actions in the computer and with machines, they can better understand what is going on—and can even alter and simplify the motions so that they remain effective but require less expertise and motion. In turn, they can transfer these lessons back to physical human behaviors. (This is a variation on Sloan’s “flip-flop”: “the process of pushing a work of art or craft from the physical world to the digital world and back.”) In short, they study ballet dancers and engineer robots so that they can find ways to help the elderly walk better and avoid falls.

This was a fun conversation—give it a listen or subscribe to the podcast through the What’s New site.

Follow-up on AI/ML in Libraries, Archives, and Museums

My thanks to HI readers who sent me recent discussions about the use of artificial intelligence/machine learning in libraries, archives, and museums, in response to HI3:

- Museums + AI, New York workshop notes, from Mia Ridge.

- Includes the slide deck from Mia’s own talk, “Operationalising AI at a national library.”

- The latest volume of Research Library Issues from the Association of Research Libraries is on the “Ethics of Artificial Intelligence”—good timing!“After decades of worries that the popularity of science and technology paradigms threaten humanistic learning and scholarship, it is now becoming evident that unique opportunities are emerging to demonstrate why humanistic expertise and informed considerations of the human condition are essential to the very future of humanity in a technological age.” —Sylvester Johnson

(Official museum description, top; most popular public tags added through Steve, bottom)

(Official museum description, top; most popular public tags added through Steve, bottom)

(Jef Raskin with a model of the Canon Cat, photo by Aza Raskin)

(Jef Raskin with a model of the Canon Cat, photo by Aza Raskin)