[An open access, pre-print version of a paper by Fred Gibbs and myself for the Autumn 2011 volume of Victorian Studies. For the final version, please see Victorian Studies at Project MUSE.]

Introduction

“Literature is an artificial universe,” author Kathryn Schulz recently declared in the New York Times Book Review, “and the written word, unlike the natural world, can’t be counted on to obey a set of laws” (Schulz). Schulz was criticizing the value of Franco Moretti’s “distant reading,” although her critique seemed more like a broadside against “culturomics,” the aggressively quantitative approach to studying culture (Michel et al.). Culturomics was coined with a nod to the data-intensive field of genomics, which studies complex biological systems using computational models rather than the more analog, descriptive models of a prior era. Schulz is far from alone in worrying about the reductionism that digital methods entail, and her negative view of the attempt to find meaningful patterns in the combined, processed text of millions of books likely predominates in the humanities.

Historians largely share this skepticism toward what many of them view as superficial approaches that focus on word units in the same way that bioinformatics focuses on DNA sequences. Many of our colleagues question the validity of text mining because they have generally found meaning in a much wider variety of cultural artifacts than just text, and, like most literary scholars, consider words themselves to be context-dependent and frequently ambiguous. Although occasionally intrigued by it, most historians have taken issue with Google’s Ngram Viewer, the search company’s tool for scanning literature by n-grams, or word units. Michael O’Malley, for example, laments that “Google ignores morphology: it ignores the meanings of words themselves when it searches…[The] Ngram Viewer reflects this disinterest in meaning. It disambiguates words, takes them entirely out of context and completely ignores their meaning…something that’s offensive to the practice of history, which depends on the meaning of words in historical context.” (O’Malley)

Such heated rhetoric—probably inflamed in the humanities by the overwhelming and largely positive attention that culturomics has received in the scientific and popular press—unfortunately has forged in many scholars’ minds a cleft between our beloved, traditional close reading and untested, computer-enhanced distant reading. But what if we could move seamlessly between traditional and computational methods as demanded by our research interests and the evidence available to us?

In the course of several research projects exploring the use of text mining in history we have come to the conclusion that it is both possible and profitable to move between these supposed methodological poles. Indeed, we have found that the most productive and thorough way to do research, given the recent availability of large archival corpora, is to have a conversation with the data in the same way that we have traditionally conversed with literature—by asking it questions, questioning what the data reflects back, and combining digital results with other evidence acquired through less-technical means.

We provide here several brief examples of this combinatorial approach that uses both textual work and technical tools. Each example shows how the technology can help flesh out prior historiography as well as provide new perspectives that advance historical interpretation. In each experiment we have tried to move beyond the more simplistic methods made available by Google’s Ngram Viewer, which traces the frequency of words in print over time with little context, transparency, or opportunity for interaction.

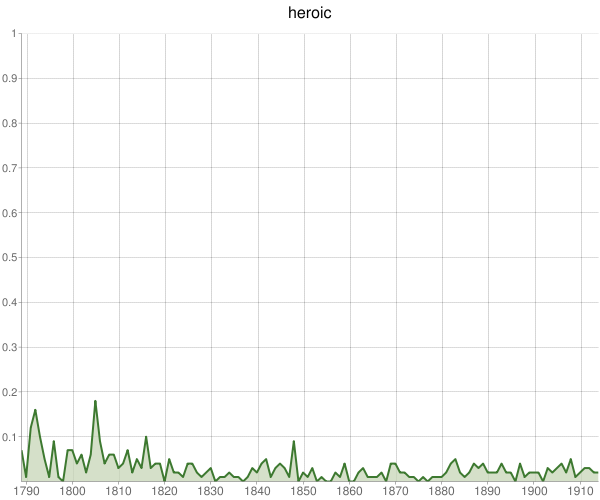

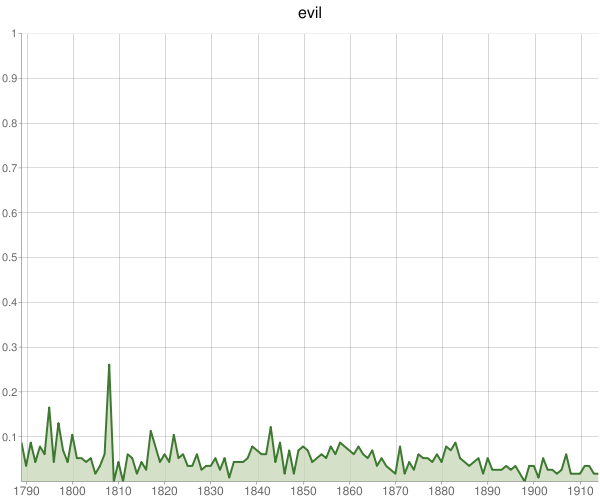

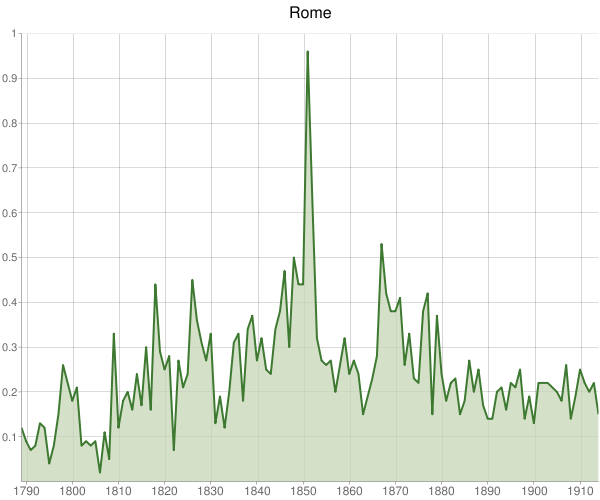

The Victorian Crisis of Faith Publications

One of our projects, funded by Google, gave us a higher level of access to their millions of scanned books, which we used to revisit Walter E. Houghton’s classic The Victorian Frame of Mind, 1830-1870 (1957). We wanted to know if the themes Houghton identified as emblematic of Victorian thought and culture—based on his close reading of some of the most famous works of literature and thought—held up against Google’s nearly comprehensive collection of over a million Victorian books. We selected keywords from each chapter of Houghton’s study—loaded words like “hope,” “faith,” and “heroism” that he called central to the Victorian mindset and character–and queried them (and their Victorian synonyms, to avoid literalism) against a special data set of titles of nineteenth-century British printed works.

The distinction between the words within the covers of a book and those on the cover is an important and overlooked one. Focusing on titles is one way to pull back from a complete lack of context for words (as is common in the Google Ngram Viewer, which searches full texts and makes no distinction about where words occur), because word choice in a book’s title is far more meaningful than word choice in a common sentence. Books obviously contain thousands of words which, by themselves, are not indicative of a book’s overall theme—or even, as O’Malley rightly points out, indicative of what a researcher is looking for. A title, on the other hand, contains the author’s and publisher’s attempt to summarize and market a book, and is thus of much greater significance (even with the occasional flowery title that defies a literal description of a book’s contents). Our title data set covered the 1,681,161 books that were published in English in the UK in the long nineteenth century, 1789-1914, normalized so that multiple printings in a year did not distort the data. (The public Google Ngram Viewer uses only about half of the printed books Google has scanned, tossing—algorithmically and often improperly—many Victorian works that appear not to be books.)

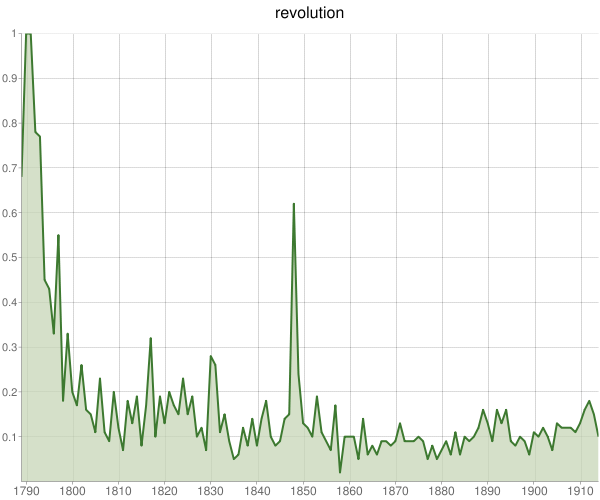

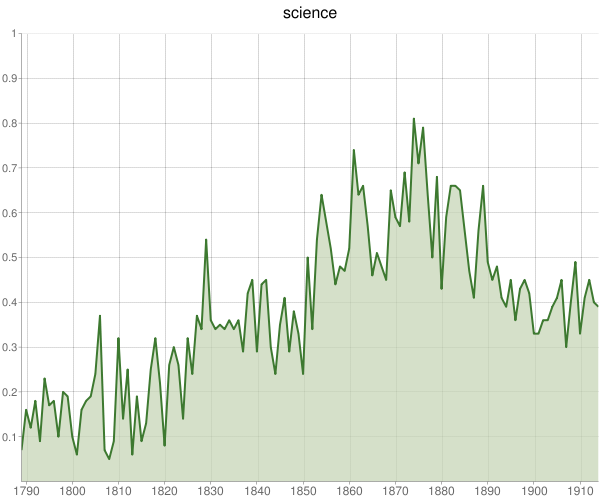

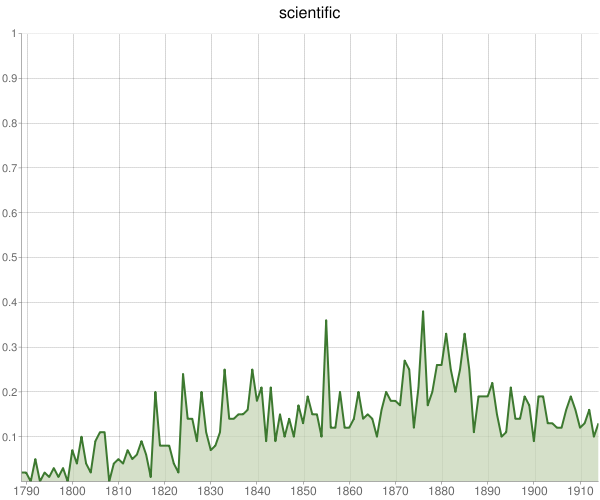

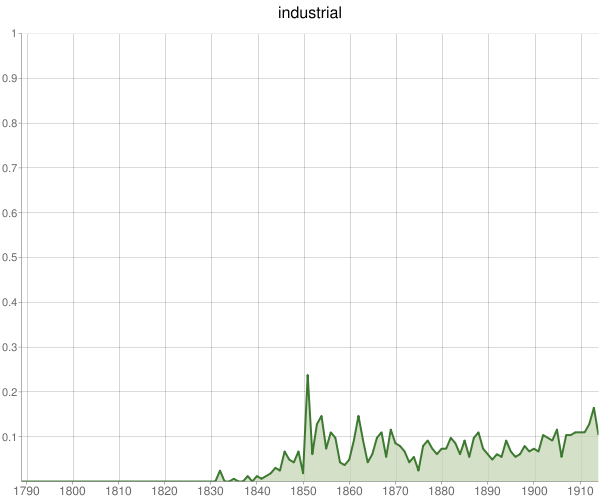

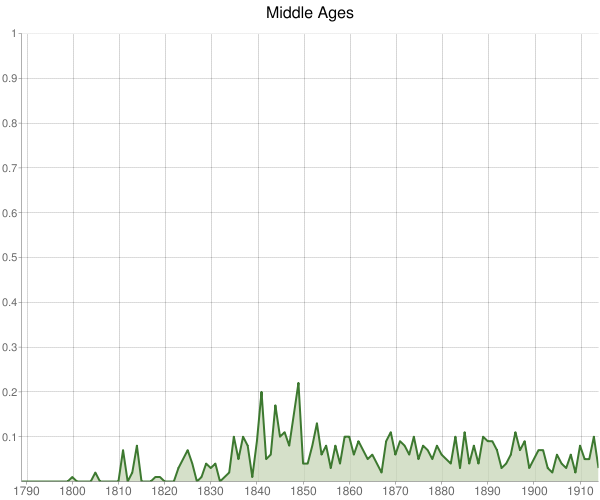

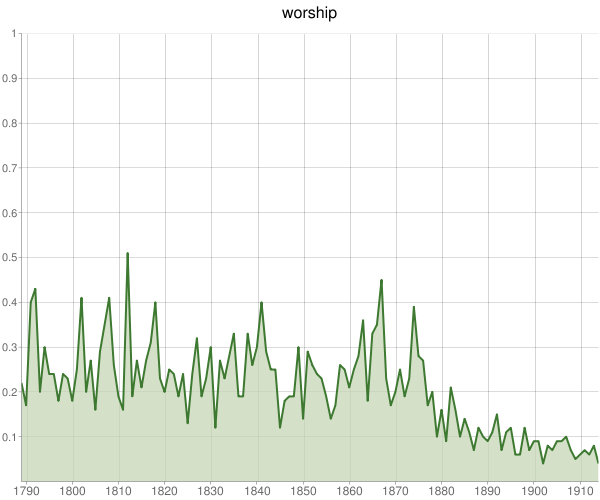

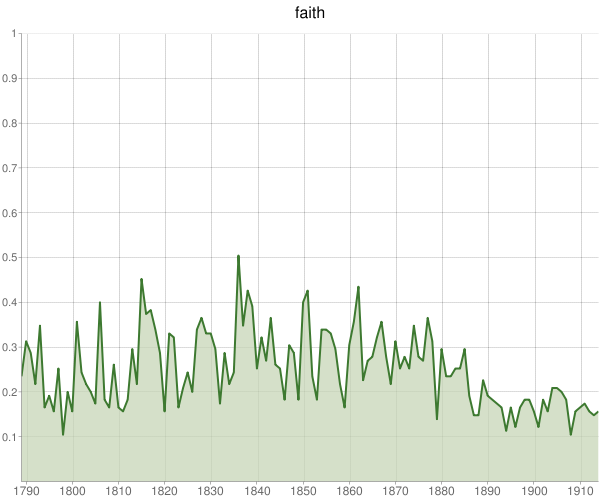

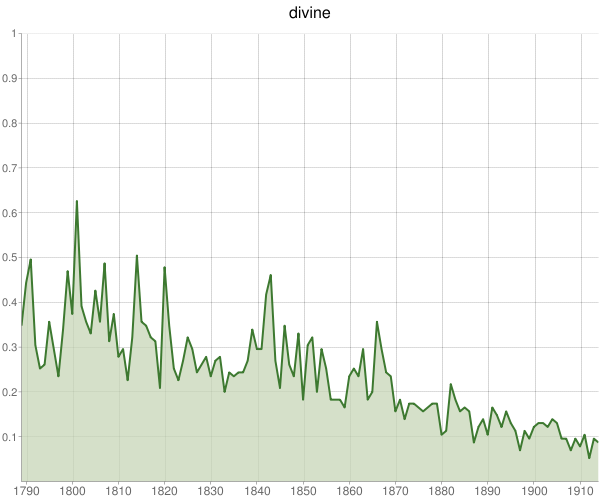

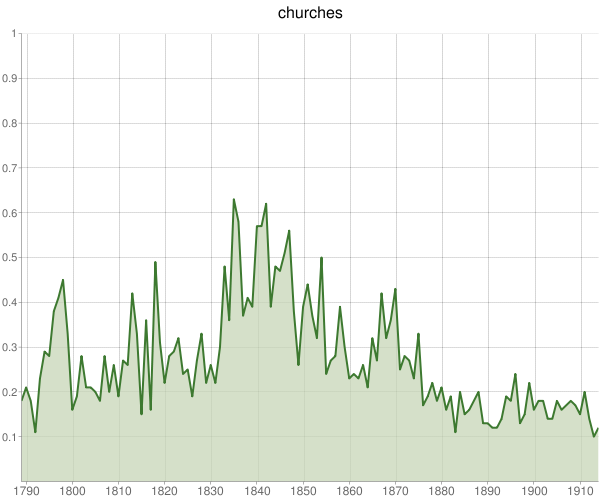

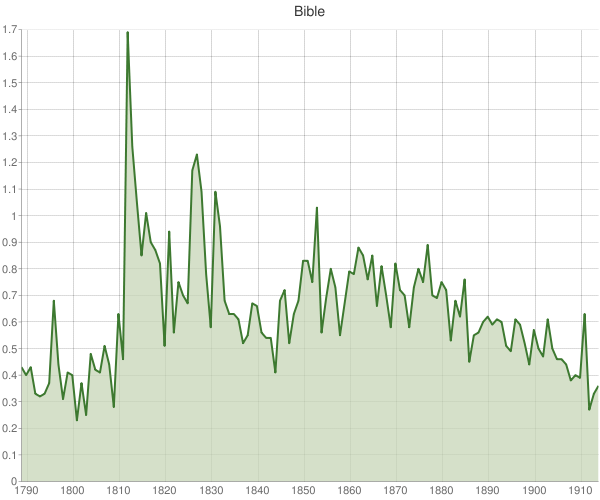

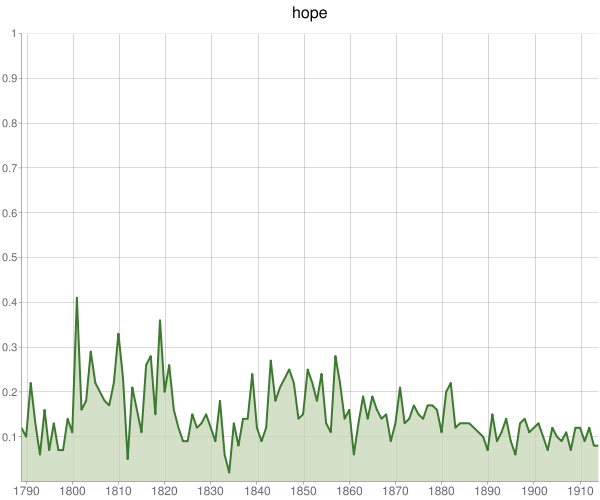

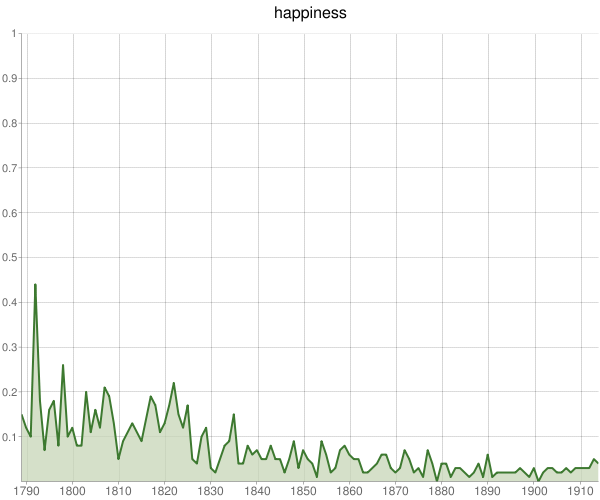

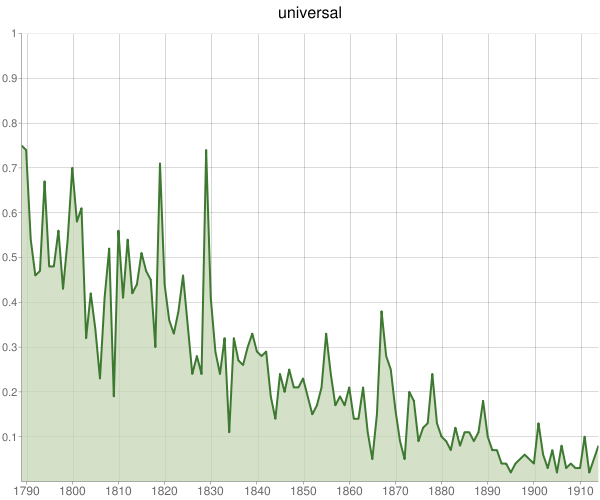

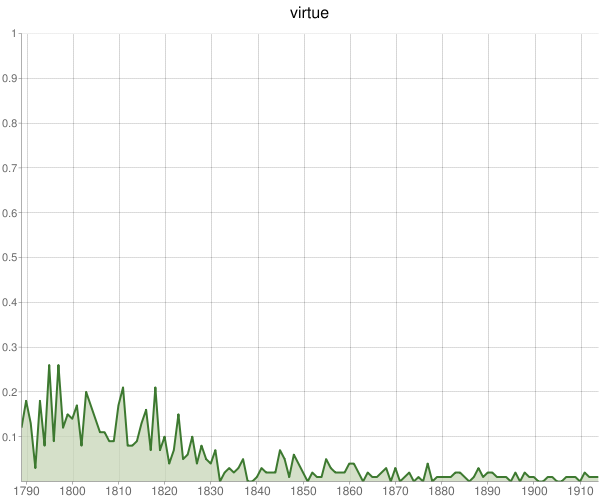

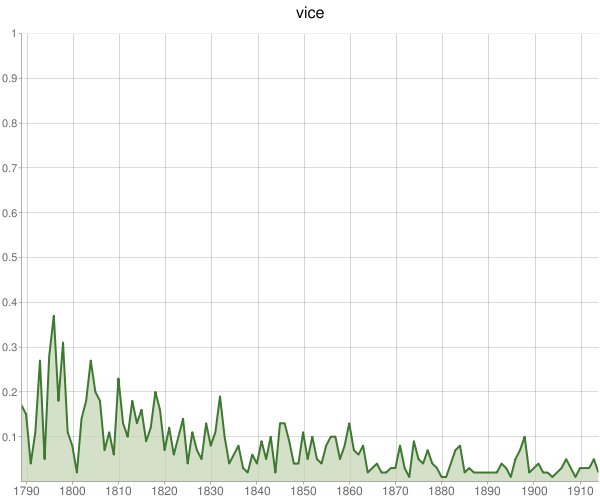

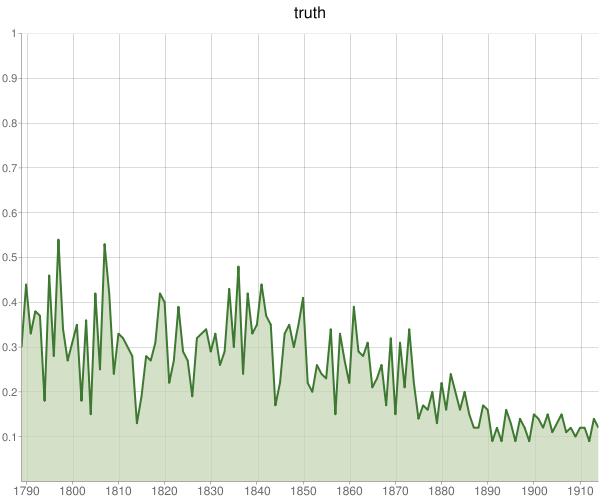

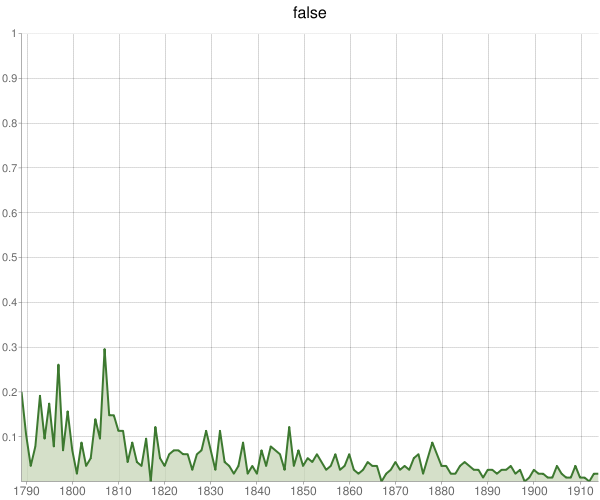

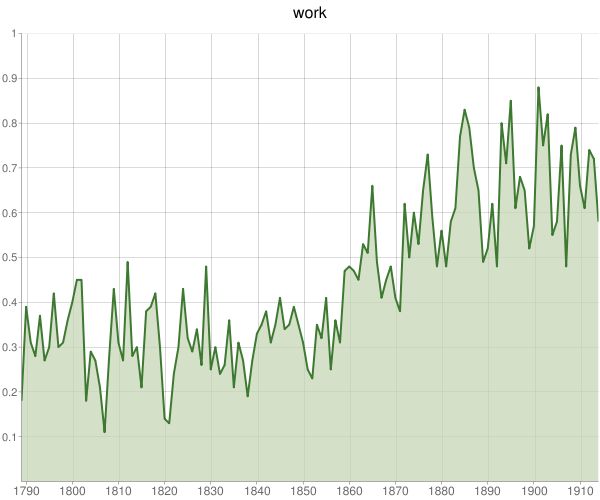

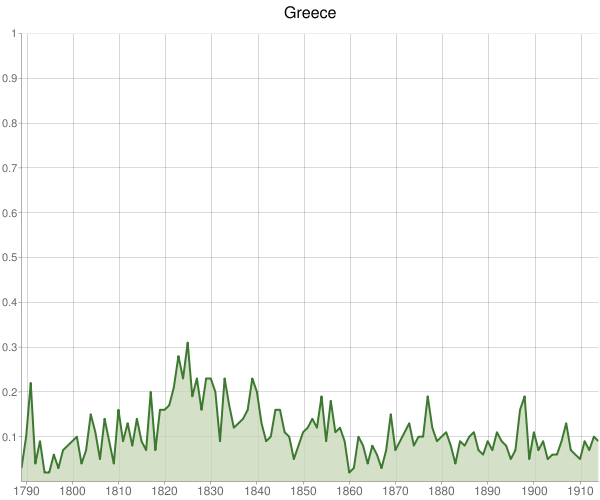

Our queries produced a large set of graphs portraying the changing frequency of thematic words in titles, which were arranged in grids for an initial, human assessment (fig. 1). Rather than accept the graphs as the final word (so to speak), we used this first, prospecting phase to think through issues of validity and significance.

Fig. 1. A grid of search results showing the frequency of a hundred words in the titles of books and their change between 1789 and 1914. Each yearly total is normalized against the total number of books produced that year, and expressed as a percentage of all publications.

Upon closer inspection, many of the graphs represented too few titles to be statistically meaningful (just a handful of books had “skepticism” in the title, for instance), showed no discernible pattern (“doubt” fluctuates wildly and randomly), or, despite an apparently significant trend, were unhelpful because of the shifting meaning of words over time.

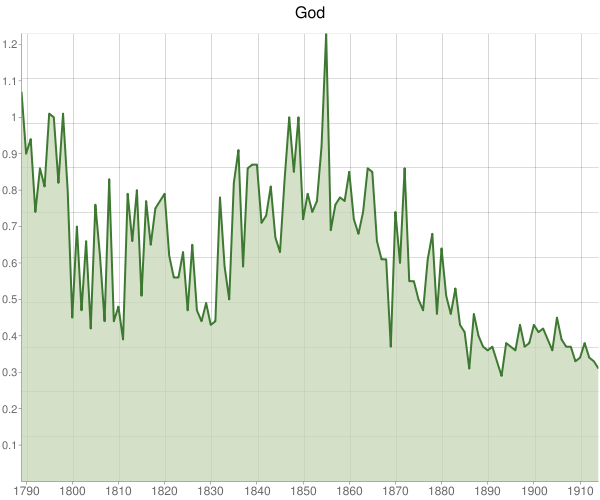

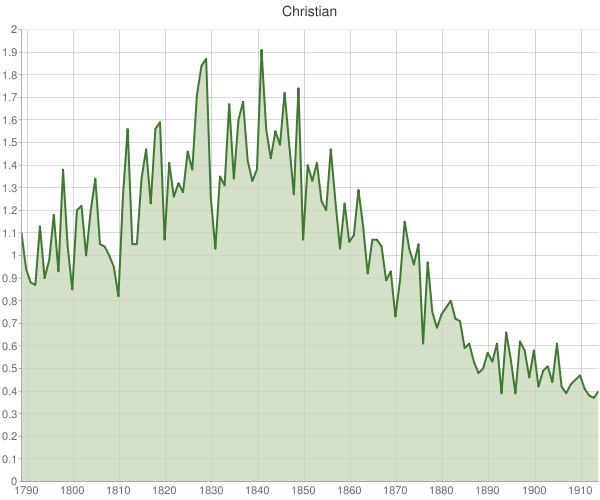

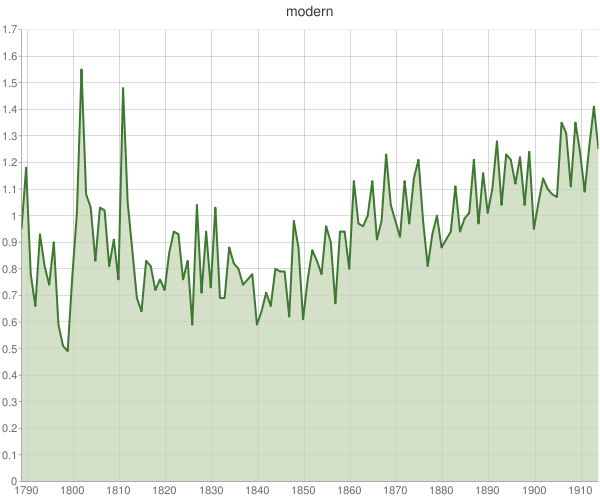

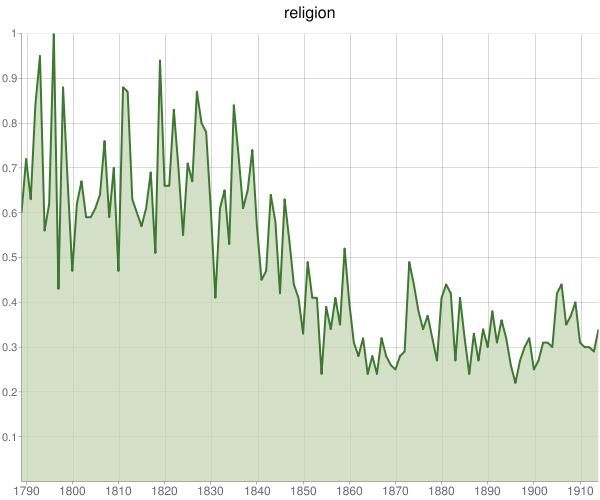

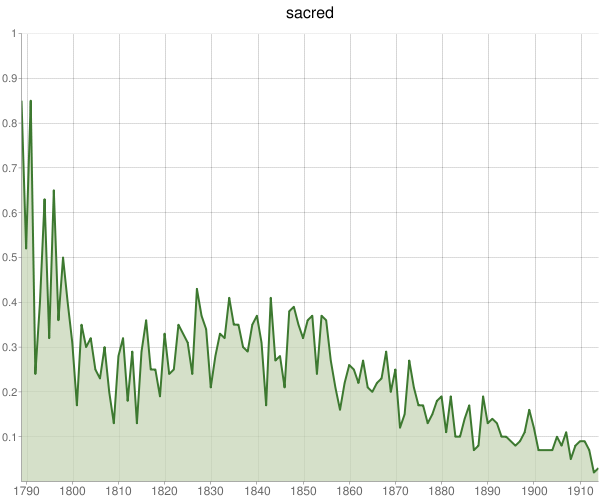

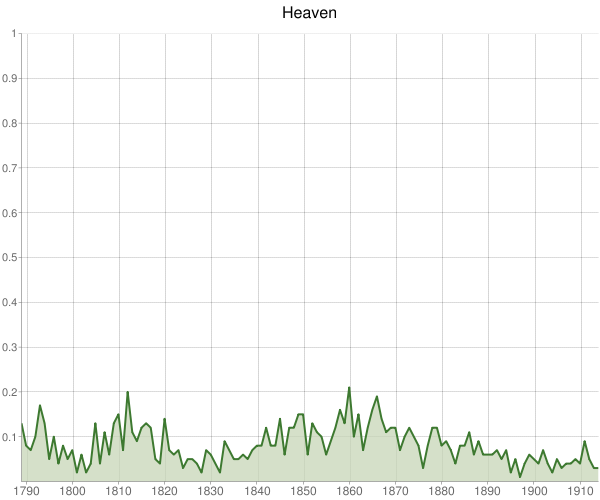

However, in this first pass at the data we were especially surprised by the sharp rise and fall of religious words in book titles, and our thoughts naturally turned to the Victorian crisis of faith, a topic Houghton also dwelled on. How did the religiosity and then secularization of nineteenth-century literature parallel that crisis, contribute to it, or reflect it? We looked more closely at book titles involving faith. For instance, books that have the words “God” or “Christian” in the title rise as a percentage of all works between the beginning of the nineteenth century and the middle of the century, and then fall precipitously thereafter. After appearing in a remarkable 1.2% of all book titles in the mid-1850s, “God” is present in just one-third of one percent of all British titles by the first World War (fig. 2). “Christian” titles peak at nearly one out of fifty books in 1841, before dropping to one out of 250 by 1913 (fig. 3). The drop is particularly steep between 1850 and 1880.

Fig. 2. The percentage of books published in each year in English in the UK from 1789-1914 that contain the word “God” in their title.

Fig. 3. The percentage of books published in each year in English in the UK from 1789-1914 that contain the word “Christian” in their title.

These charts are as striking as any portrayal of the crisis of faith that took place in the Victorian era, an important subject for literary scholars and historians alike. Moreover, they complicate the standard account of that crisis. Although there were celebrated cases of intellectuals experiencing religious doubt early in the Victorian age, most scholars believe that a more widespread challenge to religion did not occur until much later in the nineteenth century (Chadwick). Most scientists, for instance, held onto their faith even in the wake of Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859), and the supposed conflict of science and religion has proven largely illusory (Turner). However, our work shows that there was a clear collapse in religious publishing that began around the time of the 1851 Religious Census, a steep drop in divine works as a portion of the entire printed record in Britain that could use further explication. Here, publishing appears to be a leading, rather than a lagging, indicator of Victorian culture. At the very least, rather than looking at the usual canon of books, greater attention by scholars to the overall landscape of publishing is necessary to help guide further inquiries.

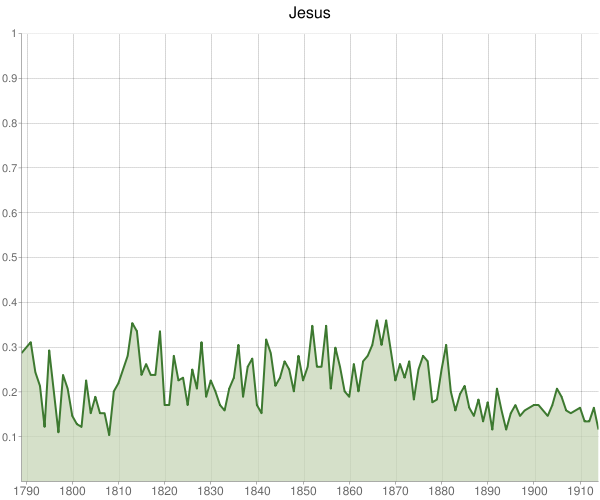

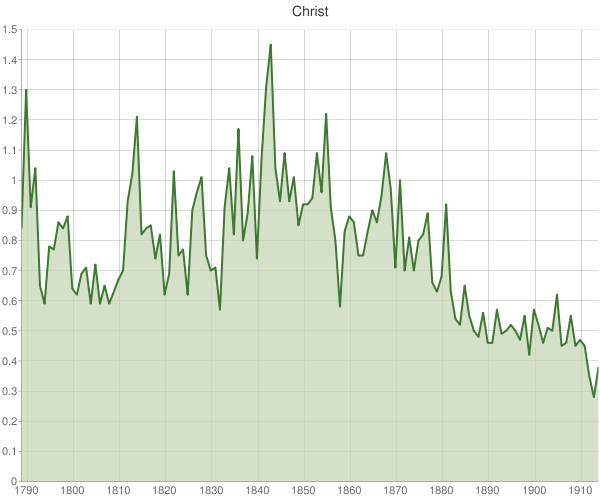

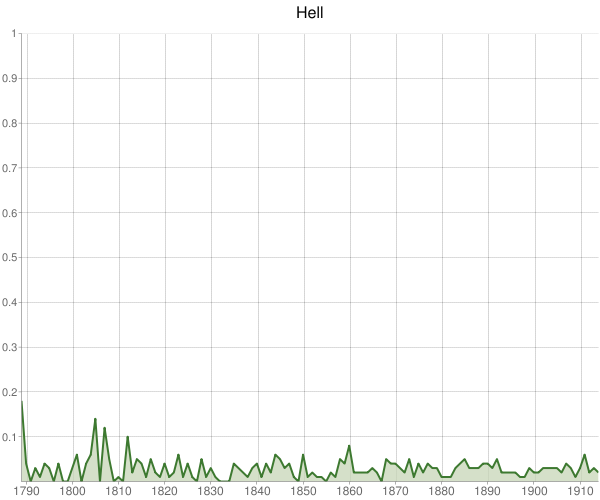

More in line with the common view of the crisis of faith is the comparative use of “Jesus” and “Christ.” Whereas the more secular “Jesus” appears at a relatively constant rate in book titles (fig. 4, albeit with some reduction between 1870 and 1890), the frequency of titles with the more religiously charged “Christ” drops by a remarkable three-quarters beginning at mid-century (fig. 5).

Fig. 4. The percentage of books published in each year in English in the UK from 1789-1914 that contain the word “Jesus” in their title.

Fig. 5. The percentage of books published in each year in English in the UK from 1789-1914 that contain the word “Christ” in their title.

Open-ended Investigations

Prospecting a large textual corpus in this way assumes that one already knows the context of one’s queries, at least in part. But text mining can also inform research on more open-ended questions, where the results of queries should be seen as signposts toward further exploration rather than conclusive evidence. As before, we must retain a skeptical eye while taking seriously what is reflected in a broader range of printed matter than we have normally examined, and how it might challenge conventional wisdom.

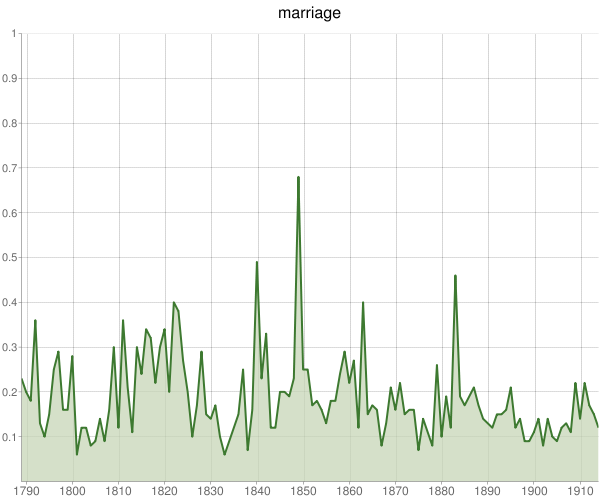

The power of text mining allows us to synthesize and compare sources that are typically studied in isolation, such as literature and court cases. For example, another text-mining project focused on the archive of Old Bailey trials brought to our attention a sharp increase in the rate of female bigamy in the late nineteenth century, and less harsh penalties for women who strayed. (For more on this project, see http://criminalintent.org.) We naturally became curious about possible parallels with how “marriage” was described in the Victorian age—that is, how, when, and why women felt at liberty to abandon troubled unions. Because one cannot ask Google’s Ngram Viewer for adjectives that describe “marriage” (scholars have to know what they are looking for in advance with this public interface), we directly queried the Google n-gram corpus for statistically significant descriptors in the Victorian age. Reading the result set of bigrams (two-word couplets) with “marriage” as the second word helped us derive a more narrow list of telling phrases. For instance, bigrams that rise significantly over the nineteenth century include “clandestine marriage,” “forbidden marriage,” “foreign marriage,” “fruitless marriage,” “hasty marriage,” “irregular marriage,” “loveless marriage,” and “mixed marriage.” Each bigram represents a good opportunity for further research on the characterization of marriage through close reading, since from our narrowed list we can easily generate a list of books the terms appear in, and many of those works are not commonly cited by scholars because they are rare or were written by less famous authors. Comparing literature and court cases in this way, we have found that descriptions of failed marriages in literature rose in parallel with male bigamy trials, and approximately two decades in advance of the increase in female bigamy trials, a phenomenon that could use further analysis through close reading.

To be sure, these open-ended investigations can sometimes fall flat because of the shifting meaning of words. For instance, although we are both historians of science and are interested in which disciplines are characterized as “sciences” in the Victorian era (and when), the word “science” retained its traditional sense of “organized knowledge” so late into the nineteenth century as to make our extraction of fields described as a “science”—ranging from political economy (368 occurrences) and human [mind and nature] (272) to medicine (105), astronomy (86), comparative mythology (66), and chemistry (65)—not particularly enlightening. Nevertheless, this prospecting arose naturally from the agnostic searching of a huge number of texts themselves, and thus, under more carefully constructed conditions, could yield some insight into how Victorians conceptualized, or at least expressed, what qualified as scientific.

Word collocation is not the only possibility, either. Another experiment looked at what Victorians thought was sinful, and how those views changed over time. With special data from Google, we were able to isolate and condense the specific contexts around the phrase “sinful to” (50 characters on either side of the phrase and including book titles in which it appears) from tens of thousands of books. This massive query of Victorian books led to a result set of nearly a hundred pages of detailed descriptions of acts and behavior Victorian writers classified as sinful. The process allowed us to scan through many more books than we could through traditional techniques, and without having to rely solely on opaque algorithms to indicate what the contexts are, since we could then look at entire sentences and even refer back to the full text when necessary.

In other words, we can remain close to the primary sources and actively engage them following computational activity. In our initial read of these thousands of “snippets” of sin (as Google calls them), we were able to trace a shift from biblically freighted terms to more secular language. It seems that the expanding realm of fiction especially provided space for new formulations of sin than did the more dominant devotional tracts of the early Victorian age.

Conclusion

Experiments such as these, inchoate as they may be, suggest how basic text mining procedures can complement existing research processes in fields such as literature and history. Although detailed exegeses of single works undoubtedly produce breakthroughs in understanding, combining evidence from multiple sources and multiple methodologies has often yielded the most robust analyses. Far from replacing existing intellectual foundations and research tactics, we see text mining as yet another tool for understanding the history of culture—without pretending to measure it quantitatively—a means complementary to how we already sift historical evidence. The best humanities work will come from synthesizing “data” from different domains; creative scholars will find ways to use text mining in concert with other cultural analytics.

In this context, isolated textual elements such as n-grams aren’t universally unhelpful; examining them can be quite informative if used appropriately and with its limitations in mind, especially as preliminary explorations combined with other forms of historical knowledge. It is not the Ngram Viewer or Google searches that are offensive to history, but rather making overblown historical claims from them alone. The most insightful humanities research will likely come not from charting individual words, but from the creative use of longer spans of text, because of the obvious additional context those spans provide. For instance, if you want to look at the history of marriage, charting the word “marriage” itself is far less interesting than seeing if it co-occurs with words like “loving” or “loveless,” or better yet extracting entire sentences around the term and consulting entire, heretofore unexplored works one finds with this method. This allows for serendipity of discovery that might not happen otherwise.

Any robust digital research methodology must allow the scholar to move easily between distant and close reading, between the bird’s eye view and the ground level of the texts themselves. Historical trends—or anomalies—might be revealed by data, but they need to be investigated in detail in order to avoid conclusions that rest on superficial evidence. This is also true for more traditional research processes that rely too heavily on just a few anecdotal examples. The hybrid approach we have briefly described here can help scholars discover exactly which books, chapters, or pages to focus on, without relying solely on sophisticated algorithms that might filter out too much. Flexibility is crucial, as there is no monolithic digital methodology that can applied to all research questions. Rather than disparage the “digital” in historical research as opposed to the spirit of humanistic inquiry, and continue to uphold a false dichotomy between close and distant reading, we prefer the best of both worlds for broader and richer inquiries than are possible using traditional methodologies alone.

Bibliography

Chadwick, Owen. The Victorian Church. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966.

Houghton, Walter Edwards. The Victorian Frame of Mind, 1830-1870. New Haven: Published for Wellesley College by Yale University Press, 1957.

Schulz, Kathryn. “The Mechanic Muse – What Is Distant Reading?” The New York Times 24 Jun. 2011, BR14.

Michel, Jean-Baptiste et al. “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books.” Science 331.6014 (2011): 176 -182.

O’Malley, Michael. “Ngrammatic.” The Aporetic, December 21, 2010, http://theaporetic.com/?p=1369.

Turner, Frank M. Between Science and Religion; the Reaction to Scientific Naturalism in Late Victorian England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974.

I’m delighted to announce that beginning this summer the

I’m delighted to announce that beginning this summer the  [This post is a version of a message I sent to

[This post is a version of a message I sent to