I’m just back from the Digital Public Library of America meeting in Chicago, and like many others I found the experience inspirational. Just two years ago a small group convened at the Radcliffe Institute and came up with a one-sentence sketch for this new library:

An open, distributed network of comprehensive online resources that would draw on the nation’s living heritage from libraries, universities, archives and museums in order to educate, inform and empower everyone in the current and future generations.

In a word: ambitious. Just two short years later, out of the efforts of that steering committee, the workstream members (I’m a convening member of the Audience and Participation workstream), over a thousand people who participated in online discussions and at three national meetings, the tireless efforts of the secretariat, and the critical leadership of Maura Marx and John Palfrey, the DPLA has gone from the drawing board to an impending beta launch in April 2013.

As I was tweeting from the Chicago meeting, distant respondents asked what the DPLA is actually going to be. What follows is what I see as some of its key initial elements, though it will undoubtedly grow substantially. (One worry expressed by many in Chicago was that the website launch in April will be seen as the totality of the DPLA, rather than a promising starting point.)

As I was tweeting from the Chicago meeting, distant respondents asked what the DPLA is actually going to be. What follows is what I see as some of its key initial elements, though it will undoubtedly grow substantially. (One worry expressed by many in Chicago was that the website launch in April will be seen as the totality of the DPLA, rather than a promising starting point.)

The primary theme in Chicago is the double-entendre subtitle of this post: coming together. It was clear to everyone at the meeting that the project was reaching fruition, garnering essential support from public funders such as the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and private foundations such as Sloan, Arcadia, and (most recently) Knight. Just as clear was the idea that what distinguishes the DPLA from—and means it will be complementary to—other libraries (online and off) is its potent combination of local and national efforts, and digital and physical footprints.

Ponds->Lakes->Ocean

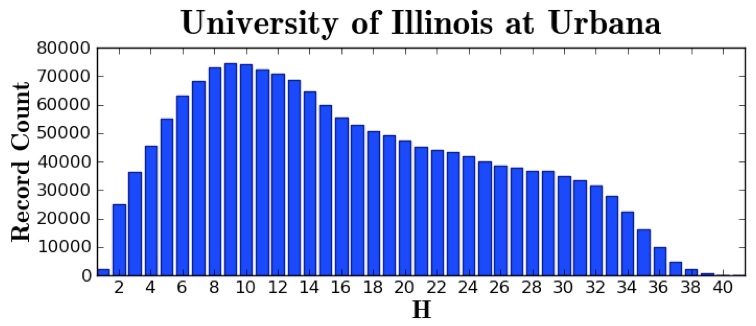

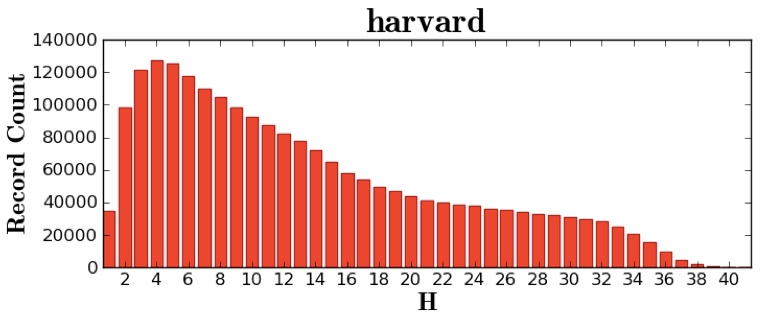

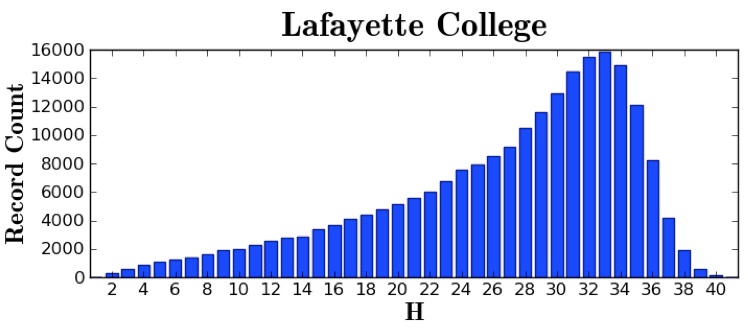

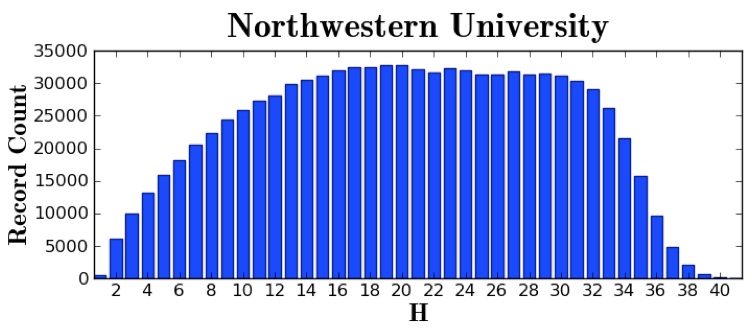

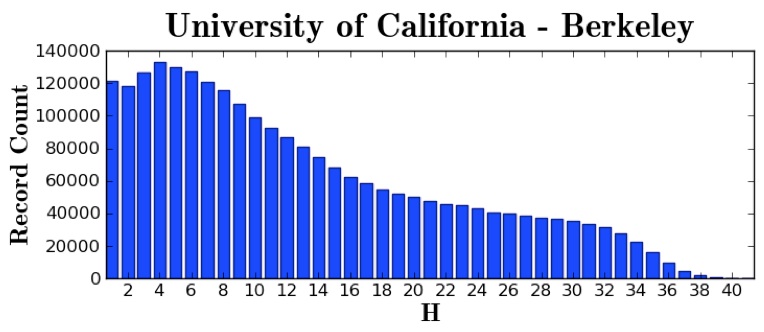

The foundation of the DPLA will be a huge store of metadata (and potentially thumbnails), culled from hundreds of sources across America. A large part of the initial collection will come from recently freed metadata about books, videos, audio recordings, images, manuscripts, and maps from large institutions like Harvard, provided under the couldn’t-be-more-permissive CC0 license. Wisely, in my estimation (perhaps colored by the fact that I’m a historian), the DPLA has sought out local archival content that has been digitized but is languishing in places that cannot solicit a large audience, and that do not have the know-how to enable modern web services such as APIs.

As I put it on Twitter, one can think of this initial set of materials (beyond the millions of metadata records from universities) as content from local ponds—small libraries, archives, museums, and historic sites—sent through streams to lakes—state digital libraries, which already exist in 40 states (a surprise to many, I suspect)—and then through rivers to the ocean—the DPLA. The DPLA will run a sophisticated technical infrastructure that will support manifold uses of this aggregation of aggregations.

Plan Nationally, Scan Locally

Since the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has worked with many local archives, museums, and historic sites, especially through our Omeka project (which has been selected as the software to run online exhibits for the DPLA), I was aware of the great cultural heritage materials that are out there in this country. The DPLA is right: much of this incredible content is effectively invisible, failing to reach national and international audiences. The DPLA will bring huge new traffic to local scanning efforts. Funding agencies such as the Institute of Museum and Library Services have already provided the resources to scan numerous items at the local level; as IMLS Director Susan Hildreth pointed out, their grant to the DPLA meant that they could bring that already-scanned content to the world—a multiplier effect.

In Chicago we discussed ways of gathering additional local content. My thought was that local libraries can brand a designated computer workstation with the blue DPLA banner, with a scanner and a nice screen showing the cultural riches of the community in slideshow mode. Directions and help will be available to scan in new documents from personal or community collections.

[My very quick mockup of a public library DPLA workstation; underlying Creative Commons photo by Flickr user JennieB]

Others envisioned “Antiques Roadshow”-type events, and Emily Gore, Director of Content at the DPLA, who coined the great term Scannebagos, spoke of mobile scanning units that could digitize content across the country.

The DPLA is not alone in sensing this great unmet need for public libraries and similar institutions to assist communities in the digital preservation of personal and local history. For instance, Bill LeFurgy, who works at the Library of Congress with the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program (NDIIPP), recently wrote:

Cultural heritage organizations have a great opportunity to fulfill their mission through what I loosely refer to as personal digital archiving…Cultural heritage institutions, as preserving entities with a public service orientation, are well-positioned to help people deal with their growing–and fragile–personal digital archives. This is a way for institutions to connect with their communities in a new way, and to thrive.

I couldn’t agree more, and although Bill focused mostly on the born-digital materials that we all have in abundance today, this mission of digital preservation can easily extend back to analog artifacts from our past. As the University of Wisconsin’s Dorothea Salo has put it, let’s turn collection development inside out, from centralized organizations to a distributed model.

When Roy and I wrote Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web, we debated the merits of “preservation through digitization.” While it may be problematic for certain kinds of rare materials, there is no doubt that local and personal collections could use this pathway. Given recent (and likely forthcoming) cuts to local archives, this seems even more meritorious.

The Best of the Digital and the Physical

The core strength, and unique feature, of the DPLA is thus that it will bring together the power and reach of the digital realm with the local community and trust in the thousands of American public libraries, museums, and historical sites—an extremely compelling combination. We are going through a difficult transition from print to digital reading, in which people are buying ebooks they cannot share or pass down to their children. The ephemerality of the digital is likely to become increasingly worrisome in this transition. At the same time people are demanding of their local libraries a greater digital engagement.

Ideally the DPLA can help public libraries and vice versa. With a stable, open DPLA combined with on-the-ground libraries, we can begin to articulate a model that protects and makes accessible our cultural heritage through and beyond the digital transition. For the foreseeable future public libraries will continue to house physical materials—the continued wonders of the codex—as well as provide access to the internet for the still significant minority without such access. And the DPLA can serve as a digital attic and distribution center for those libraries.

The key point, made by DPLA board member Laura DeBonis, is that with this physical footprint in communities the DPLA can do things that Google and other dotcoms cannot. She did not mean this as a criticism of Google Books (a project she was involved with when she worked at Google), which has done impressive work in scanning over 20 million books. But the DPLA has an incredible potential local network it can take advantage of to reach out to millions of people and have them share their history—in general, to democratize the access to knowledge.

It is critical to underline this point: the DPLA will be much more than its technical infrastructure. It will succeed or fail not on its web services but on its ability to connect with localities across the United States and have them use—and contribute—to the DPLA.

A Community-Oriented Platform

Having said that, the technical infrastructure is looking solid. But here, too, the Technical Aspects workstream is keeping foremost in their mind community uses. As workstream member David Weinberger has written, we can imagine a future library as a platform, one that serves communities:

In many instances, those communities will be defined geographically, whether it’s a town’s local library or a university community; in some instances, the community will be defined by interest, not by geography. In either case, serving a defined community has two advantages. First, it enables libraries to accomplish the mission they’ve been funded to accomplish. Second, user networks depend upon and assume local knowledge, interests, and norms. While a local library platform should interoperate with the rest of the world’s library platforms, it may do best if it is distinctively local…

Just as each project created by a developer makes it easier for the next developer to create the next app, each interaction by users ought to make the library platform a little smarter, a little wiser, a little more tuned to its users interests. Further, the visible presence of neighbors and the availability of their work will not only make the library an ever more essential piece of the locality’s infrastructure, it can make the local community itself more coherent and humane.

Conceiving of the library as a platform not only opens a range of new services and provides for a continuous increase in the library’s value, it also does something libraries urgently need to do: it changes the criteria of success. A library platform should be measured less on the circulation of its works than in the circulation of the ideas and passions these works spark — from how many works are checked out to the community’s engagement with its own grappling with those works. This is not only a metric that libraries-as-platforms can excel at, it is in fact a measure of what has always been the truest value of libraries.

In that sense, by becoming a platform the library can better fulfill the abiding mission it set itself: to be a civic institution essential to democracy.

Nicely put.

New Uses for Local History

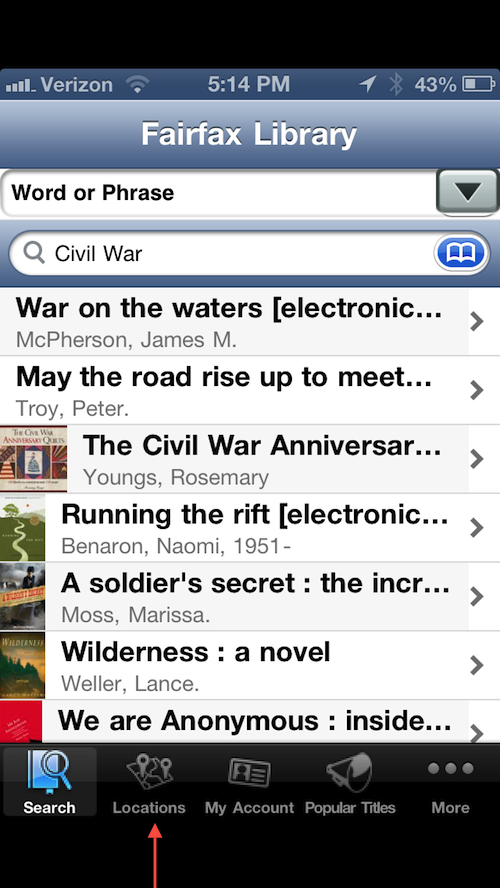

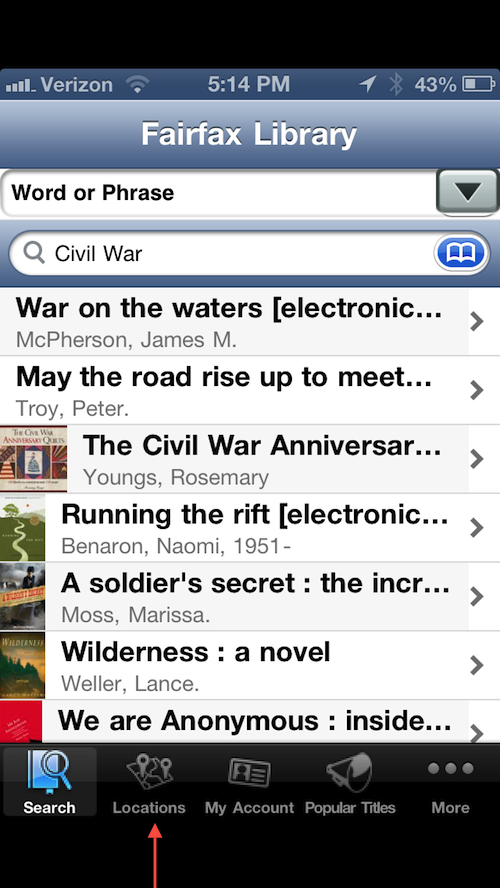

It’s not hard to imagine many apps and sites incorporating the DPLA’s aggregation of local historical content. It struck me that an easy first step is incorporation of the DPLA into existing public library apps. Here in Fairfax, Virginia, our county has an app that is fairly rudimentary but quickly becoming popular because it replaces that library card you can never find. (The app also can alert you to available holds and new titles, and search the catalog.)

I fired up the Fairfax Library app on my phone at the Chicago meeting, and although the county doesn’t know it yet, there’s already a slot for the DPLA in the app. That “local” tab at the bottom can sense where you are and direct you to nearby physical collections; through the DPLA API it will be trivial to also show people digitized items from their community or current locale.

Granted, Fairfax County is affluent and has a well-capitalized public library system that can afford a smartphone app. But my guess is the app is fairly simple and was probably built from a framework other libraries use (indeed, it may be part of Fairfax County’s ILS vendor package), so DPLA integration could happen with many public libraries in this way. For libraries without such resources, I can imagine local hackfests lending a hand, perhaps working from a base app that can be customized for different public libraries easily.

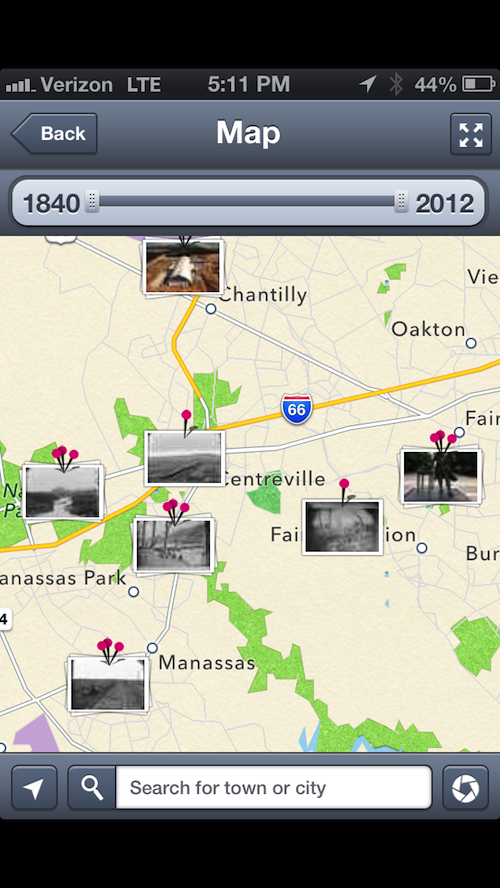

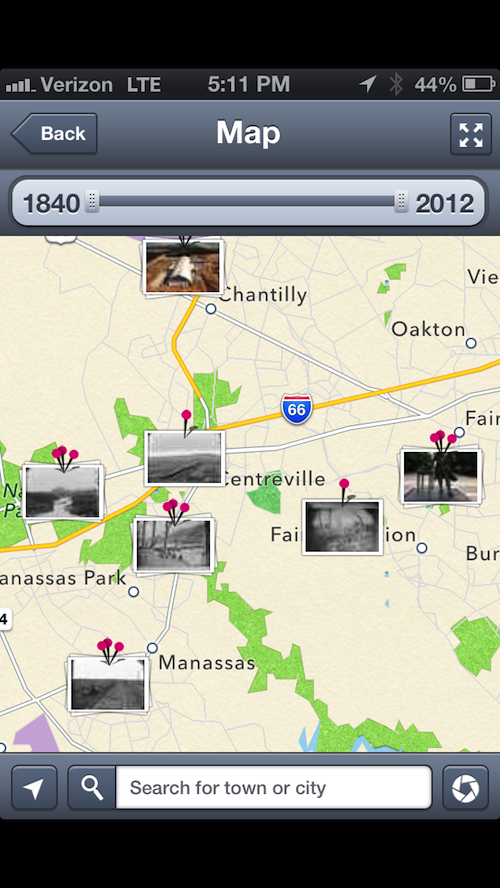

Long-time readers of this blog can identify dozens of other apps that will be hungry for DPLA content. The idea of marrying geolocation with historical materials has flourished in the last two years, with apps like HistoryPin showing how people can find out about the history around them.

Even Google has gotten into the act of location + history with its recently launched Field Trip app. I suspect countless similar projects will be enhanced by, or based on, the DPLA API.

Moreover, geolocating historical documents is but one way to use the technical infrastructure of the DPLA. As the technical working group has wisely noted, the platform exists for unintended uses as well as obvious ones. To explore the many possibilities, there will next be an “Appfest” at the Chattanooga Public Library on November 8-9, 2012. And I’m planning a DPLA hacking session here at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media for December 6, 2012, concurrent with an Audience and Participation workstream meeting. Stay tuned for details.

The Speculative

Only hinted at in Chicago, but worthy of greater thought, is what else we might do with the combination of thousands of public libraries and the DPLA. This area is more speculative, for reasons ranging from legal considerations to the changing nature of reading. The strong fair use arguments that won the day in the Authors Guild v. HathiTrust case (the ruling was handed down the day before DPLA Midwest) may—may— enable new kinds of sharing of digital materials within geofenced areas such as public libraries. (Chicago did not have a report from DPLA’s legal workstream, so we await their understanding of the shifting copyright and fair use landscape in the wake of landmark positive rulings in the HathiTrust and Georgia State cases.)

Perhaps the public library can achieve, in the medium term, some kind of hybrid physical-digital browsability as imagined in this video of a French bookstore from the near future, in which a simple scan of a book using a tablet transfers an e-text to the tablet. The video gets at the ongoing need for in-person reading advice and the superior browsability of physical bookshelves.

I’ve been tracking a number of these speculative exercises, such as the student projects in Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Library Test Kitchen, which experiments with media transformations of libraries. I suspect that bookfuturists will think of other potential physical/digital hybrids.

But we need not get fancy. More obvious benefits abound. The DPLA will be widely used by teachers and students, with scans being placed into syllabi and contextualized by scholars. Judging by the traffic RRCHNM’s educational sites and digital archives get, I expect a huge waiting audience for this. I can also anticipate local groups of readers and historical enthusiasts gathering in person to discuss works from the DPLA.

Momentum, but Much Left to Do

To be sure, many tough challenges still await the DPLA. Largely absent from the discussion in Chicago, with its focus on local history, is the need to see what the digital library can do with books. After all, the majority of circulations from public libraries are popular, in-copyright works, and despite great unique local content the public may expect that P in DPLA to provide a bit more of what they are used to from their local library. Finding ways to have big publishers share at least some books through the system—or perhaps start with smaller publishers willing to experiment with new models of distribution—will be an important piece of the puzzle.

As I noted at the start, the DPLA now has funding from public and private sources, but it will have to raise much, much more, not easy in these austere times. It needs a staff with the energy to match the ambition of the project, and the chops to execute a large digital project that also has in-person connections in 50 states.

A big challenge, indeed. But who wouldn’t like a public, open, digital library that draws from across the United States “to educate, inform and empower everyone”?

As I was tweeting from the Chicago meeting, distant respondents asked what the DPLA is actually going to be. What follows is what I see as some of its key initial elements, though it will undoubtedly grow substantially. (One worry expressed by many in Chicago was that the website launch in April will be seen as the totality of the DPLA, rather than a promising starting point.)

As I was tweeting from the Chicago meeting, distant respondents asked what the DPLA is actually going to be. What follows is what I see as some of its key initial elements, though it will undoubtedly grow substantially. (One worry expressed by many in Chicago was that the website launch in April will be seen as the totality of the DPLA, rather than a promising starting point.)