René Descartes designed a deck of playing cards that also functioned as flash cards to learn geometry and mechanics. (King of Clubs from The use of the geometrical playing-cards, as also A discourse of the mechanick powers. By Monsi. Des-Cartes. Translated from his own manuscript copy. Printed and sold by J. Moxon at the Atlas in Warwick Lane, London. Via the Beinecke Library, from which you can download the entire deck.)

In this issue, I want to open a conversation about a technology of our age that hasn’t quite worked out the way we all had hoped—and by we, I mean those of us who care about the composition and transmission of ideas, which I believe includes everyone on this list.

Twenty years ago, literary critic Sven Birkerts reviewed the new technology of ebooks and e-readers for the short-lived internet magazine Feed. They sent him a Rocket eBook and a SoftBook, and he duly turned them on and settled into his comfy chair. What followed, however, was anything but comfy:

If there is a hell on earth for people with certain technological antipathies, then I was roasting there last Saturday afternoon when I found myself trapped in some demonic Ourobouros circuit system wherein the snake was not only devouring its own tail, but was also sucking from me the faith that anything would ever make sense again.

Reader, it was not a positive review. But surely, the two decades that separate the present day from Birkerts’ 1999 e-reader fiasco have provided us with vastly improved technology and a much healthier ecosystem for digital books?

Alas, we all know the answer to that. Ten years after Birkerts’ Feed review of existing e-readers, Amazon released the Kindle, which was more polished than the Rocket eBook and SoftBook (both of which met the ignominious end of being purchased in a fire sale by the parent company of TV Guide), and ten years after that, we are where we are: the Kindle’s hardware and software are serviceable but not delightful, and the ebook market is a mess that is dominated by that very same company. As Dan Frommer put it in “How Amazon blew it with the Kindle”:

It’s not that the Kindle is bad — it’s not bad, it’s fine. And it’s not that on paper, it’s a failure or flop — Amazon thoroughly dominates the ebook and reader markets, however niche they have become… It’s that the Kindle isn’t nearly the product or platform it could have been, and hasn’t profoundly furthered the concept of reading or books. It’s boring and has no soul. And readers — and books — deserve better.

Amen. Contrast this with other technologies in wide use today, from the laptop to the smartphone, where there were early, clear visions of what they might be and how they might function, ideals toward which companies like Apple kept refining their products. Think about the Dynabook aspirational concept from 1972 or the Knowledge Navigator from 1987. Meanwhile, ebooks and e-readers have more or less ignored potentially helpful book futurism.

There have been countless good examples, exciting visions, of what might have been. For instance, in 2007 the French publisher Editis created a video showing a rather nice end-to-end system in which a reader goes into a local bookstore, gets advice on what to read from the proprietor, pulls a print book off the shelf, holds a reading device above the book (the device looks a lot like the forthcoming book-like, foldable, dual-screen Neo from Microsoft), which then transfers a nice digital version of the book, in color, to his e-reader.

Ebooks and print books, living in perfect harmony, while maintaining a diversified and easy-to-understand ecosystem of culture. Instead what we have is a discordant hodgepodge of various technologies, business models, and confused readers who often can’t get that end-to-end system to work for them.

I was in a presentation by someone from Apple in 2011 that forecast the exact moment when ebook sales would surpass print book sales (I believe it was sometime in 2016 according to his Keynote slides); that, of course, never happened. Ebooks ended up plateauing at about a third of the market. (As I have written elsewhere, ebooks have made more serious inroads in academic, rather than public, libraries.)

It is worth asking why ebooks and e-readers like the Kindle treaded water after swimming a couple of laps. I’m not sure I can fully diagnose what happened (I would love to hear your thoughts), but I think there are many elements, all of which interact as part of the book production and consumption ecosystem. Certainly a good portion of the explanation has to do with the still-delightful artifact of the print book and our physical interactions with it. As Birkerts identified twenty years ago:

With the e-books, focus is removed to the section isolated on the screen and perhaps to the few residues remaining from the pages immediately preceding. The Alzheimer’s effect, one might call it. Or more benignly, the cannabis effect. Which is why Alice in Wonderland, that ur-text of the mind-expanded ’60s, makes such a perfect demo-model. For Alice too, proceeds by erasing the past at every moment, subsuming it entirely in every new adventure that develops. It has the logic of a dream – it is a dream – and so does this peculiarly linear reading mode, more than one would wish.

No context, then, and no sense of depth. I suddenly understood how important – psychologically – is our feeling of entering and working our way through a book. Reading as journey, reading as palpable accomplishment – let’s not underestimate these. The sensation of depth is secured, in some part at least, by the turning of real pages: the motion, slight though it is, helps to create immersion in a way that thumb clicks never can. When my wife tells me, “I’m in the middle of the new Barbara Kingsolver,” she means it literally as well as figuratively.

But I think there are other reasons that the technology of the ebook never lived up to grander expectations, reasons that have less to do with the reader’s interaction with the ebook—let’s call that the demand side—and more to do with the supply side, the way that ebooks are provided to readers through markets and platforms. This is often the opposite of delightful.

That rough underbelly has been exposed recently with the brouhaha about Macmillan preventing libraries from purchasing new ebooks for the first eight weeks after their release, with the exception of a single copy for each library system. (I suspect that this single copy, which perhaps seemed to Macmillan as a considerate bone-throw to the libraries, actually made it feel worse to librarians, for reasons I will leave to behavioral economists and the poor schmuck at the New York Public Library who has to explain to a patron why NYPL apparently bought a single copy of a popular new ebook in a city of millions.)

From the supply side, and especially from the perspective of libraries, the ebook marketplace is simply ridiculous. As briefly as I can put it, here’s how my library goes about purchasing an ebook:

First, we need to look at the various ebook vendors to see who can provide access to the desired book. Then we need to weigh access and rights models, which vary wildly, as well as price, which can also vary wildly, all while thinking about our long-term budget/access/preservation matrix.

But wait, there’s more. Much more. We generally encounter four different acquisition models (my thanks to Janet Morrow of our library for this outline): 1) outright purchase, just like a print book, easy peasy, generally costs a lot even though it’s just bits (we pay an average of over $40 per book this way), which gives us perpetual access with the least digital rights management (DRM) on the ebooks, which has an impact on sustainable access over time; 2) subscription access: you need to keep paying each year to get access, and the provider can pull titles on you at any time, plus you also get lots of DRM, but there’s a low cost per title (~$1 a book per year); 3) demand-driven/patron-driven acquisition: you don’t get the actual ebook, just a bibliographic record for your library’s online system, until someone chooses to download a book, or reads some chunk of it online, which then costs you, say ~$5; 4) evidence-based acquisitions, in which we pay a set cost for unlimited access to a set of titles for a year and then at the end of the year we can use our deposit to buy some of the titles (<$1/book/year for the set, and then ~$60/book for those we purchase).

As I hope you can tell, this way lies madness. Just from a library workflow and budgetary perspective, this is insanely difficult to get right or even to make a decision in the first place, never mind the different ebook interfaces, download mechanisms, storage, DRM locks, and other elements that the library patron interacts with once the library has made the purchase/rental/subscription. Because of the devilish complexity of the supply side of the ebook market, we recently participated in a pilot with a software company to develop a NASA-grade dashboard for making ebook decisions. Should I, as the university librarian, spend $1, $5, or $40, should I buy a small number of favored books outright, or subscribe to a much wider range of books but not really own them, or or or.

Thankfully I have a crack staff, including Janet, who handles this complexity, but I ask you to think about this: how does the maddeningly discordant ebook market and its business models skew our collection—what we choose to acquire and provide access to? And forget Macmillan’s eight weeks: what does this byzantine system mean for the availability, discoverability, and preservation of ebooks in 10, 50, or 100 years?

We should be able to do better. That’s why it’s good to see the Digital Public Library of America (where I used to be executive director) establishing a nonprofit, library-run ebook marketplace, with more consistent supply-side terms and technical mechanisms. Other solutions need to be proposed and tried. Please. We can’t have a decent future for ebooks unless we start imagining alternatives.

Onto a sunnier library topic: We are beginning a renovation of our main library at Northeastern University, Snell Library, and have been talking with architects (some of them very well-known), and I’ve found the discussions utterly invigorating. I would like to find some way to blog or newsletter about the process we will go through over the next few years, and to think aloud about the (re)design and (future) function of the library. I’m not sure if that should occur in this space or elsewhere, although the thought of launching another outlet fills me with dread. Let me know if this topic would interest you, and if I should include it here.

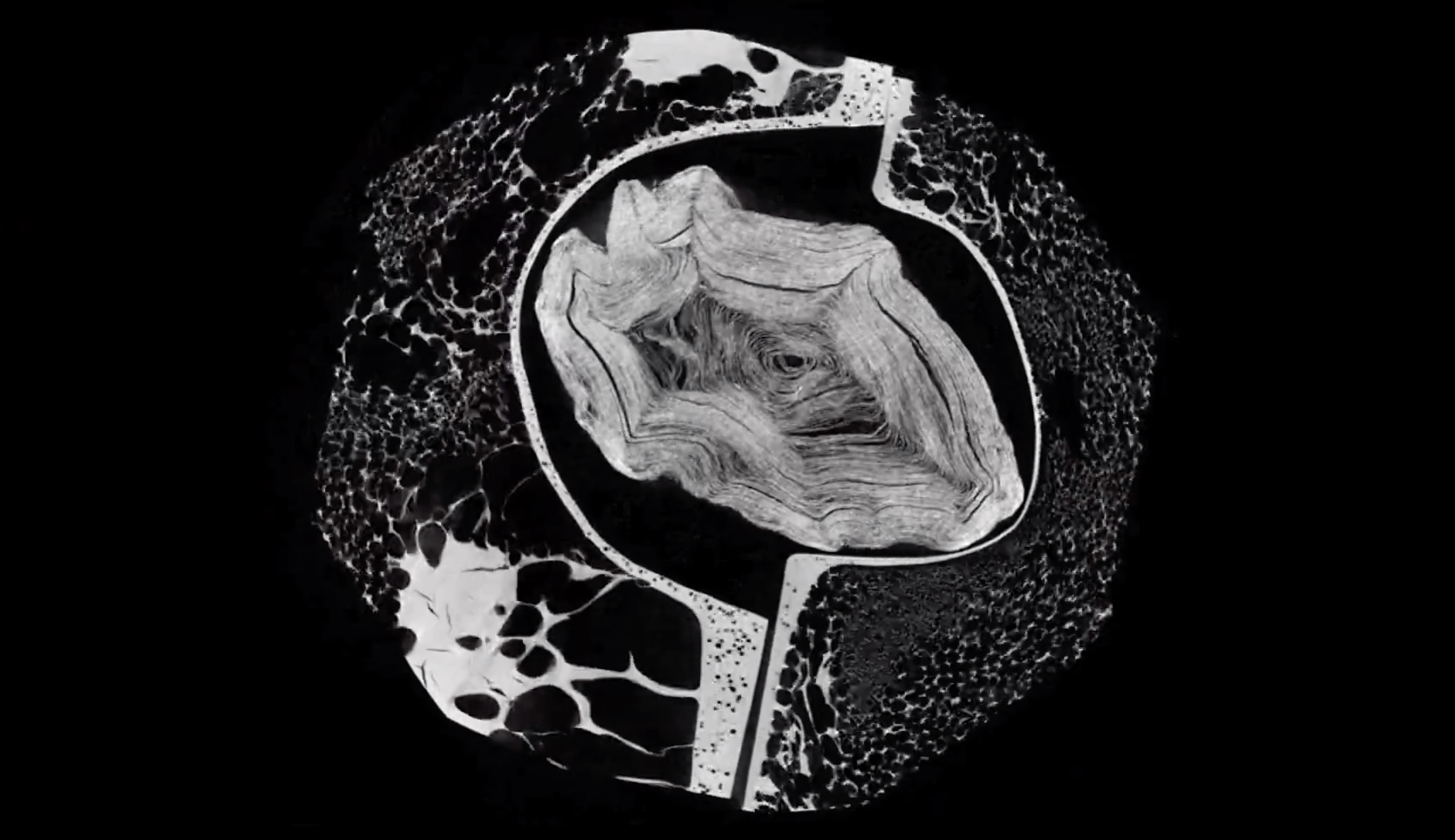

On the latest What’s New podcast from the Northeastern University Library, my guest is Louise Skinnari, one of the physicists who works on the Large Hadron Collider. She takes us inside CERN and the LHC, explains the elementary particles and what they have found by smashing them at the speed of light, and yours truly says “wow” a lot. Because there’s so much wow there: the search for the Higgs boson, the fact that the LHC produces 40 terabytes of data per second, the elusiveness of dark matter. Louise is brilliant and is helping to upgrade the LHC with a new sensor that sounds like it’s straight out of Star Trek: the Compact Muon Solenoid. She is also investigating the nature of the top quark, which has some unusual and magical properties. Tune in and subscribe to the podcast!

(Official museum description, top; most popular public tags added through Steve, bottom)

(Official museum description, top; most popular public tags added through Steve, bottom)

(Jef Raskin with a model of the Canon Cat, photo by Aza Raskin)

(Jef Raskin with a model of the Canon Cat, photo by Aza Raskin)