[A contribution to the Hacking the Academy book project. Tom Scheinfeldt and I are crowdsourcing the content of that book in one week.]

In my post The Social Contract of Scholarly Publishing, I noted that there is a supply side and a demand side to scholarly communication:

The supply side is the creation of scholarly works, including writing, peer review, editing, and the form of publication. The demand side is much more elusive—the mental state of the audience that leads them to “buy” what the supply side has produced. In order for the social contract to work, for engaged reading to happen and for credit to be given to the author (or editor of a scholarly collection), both sides need to be aligned properly.

I would now like to analyze and influence that critical mental state of the scholar by appealing to four emotions and values, to try both to increase the supply of open access scholarship and to prod scholars to be more receptive to scholarship that takes place outside of the traditional publishing system.

1. Impartiality

In my second year in college I had one of those late-night discussions where half-baked thoughts are exchanged and everyone tries to impress each other with how smart and hip they are. A sophomoric gabfest, literally and figuratively. The conversation inevitably turned to music. I reeled off the names of bands I thought would get me the most respect. Another, far more mature student then said something that caught everyone off guard: “Well, to be honest, I just like good music.” We all laughed—and then realized how true that statement was. And secretly, we all did like a wide variety of music, from rock to bluegrass to big band jazz.

Upon reflection, many of the best things we discover in scholarship—and life—are found in this way: by disregarding popularity and packaging and approaching creative works without prejudice. We wouldn’t think much of Moby-Dick if Carl Van Doren hadn’t looked past decades of mixed reviews to find the genius in Melville’s writing. Art historians have similarly unearthed talented artists who did their work outside of the royal academies or art schools. As the unpretentious wine writer Alexis Lichine shrewdly said in the face of fancy labels and appeals to mythical “terroir”: “There is no substitute for pulling corks.”

Writing is writing and good is good, no matter the venue of publication or what the crowd thinks. Scholars surely understand that on a deep level, yet many persist in the valuing venue and medium over the content itself. This is especially true at crucial moments, such as promotion and tenure. Surely we can reorient ourselves to our true core value—to honor creativity and quality—which will still guide us to many traditionally published works but will also allow us to consider works in some nontraditional venues such as new open access journals, blogs or articles written and posted on a personal website or institutional repository, or non-narrative digital projects.

2. Passion

Do you get up in the morning wondering what journal you’re going to publish in next or how you’re going to spend your $10 royalty check? Neither do I, nor do most scholars. We wake up with ideas swirling around inside our head about the topic we’re currently thinking about, and the act of writing is a way to satisfy our obsession and communicate our ideas to others. Being a scholar is an affliction of which scholarship is a symptom. If you’re publishing primarily for careerist reasons and don’t deeply care about your subject matter, let me recommend you find another career.

The entire commercial apparatus of the existing publishing system merely leeches on our scholarly passion and the writing that passion inevitably creates. The system is far from perfect for maximizing the spread of our ideas, not to mention the economic bind it has put our institutions in. If you were designing a system of scholarly communication today, in the age of the web, would it look like the one we have today? Disparage bloggers all you like, but they control their communication platform, the outlet for their passion, and most scholars and academic institutions don’t.

3. Shame

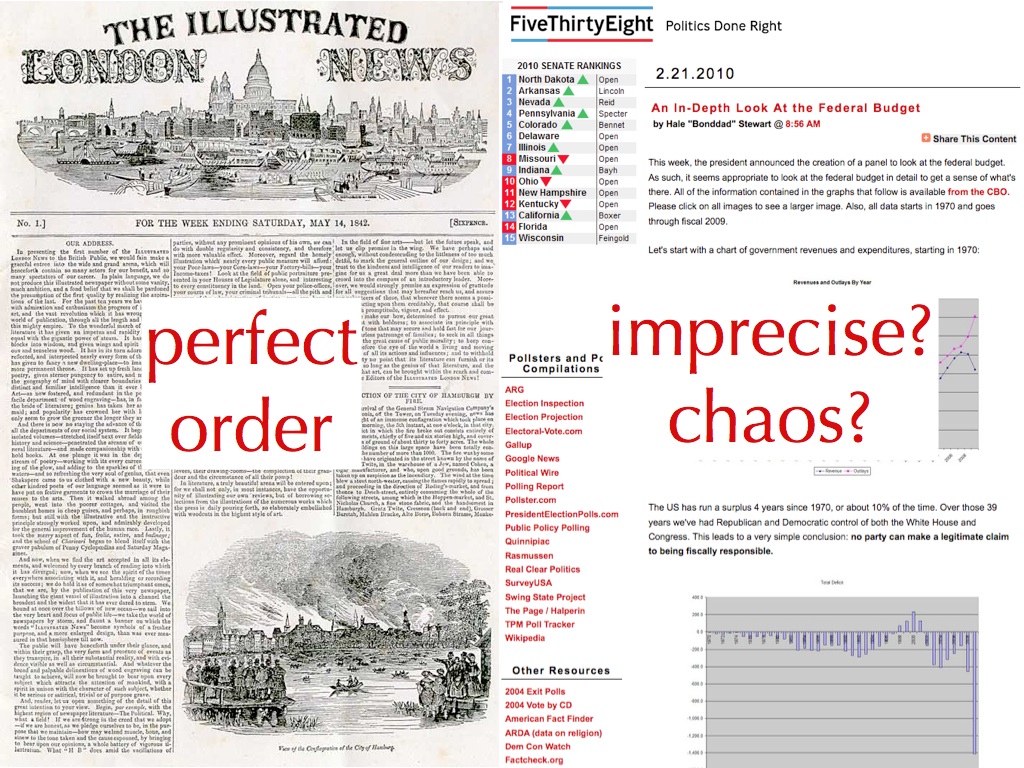

This spring Ithaka, the nonprofit that runs JSTOR and that has a research wing to study the transition of academia into the digital age, put out a report based on their survey of faculty in 2009. The report has two major conclusions. First, scholars are increasingly using online resources like Google Books as a starting point for their research rather than the physical library. That is, they have become comfortable in certain respects with “going digital.”

But at the same time the Ithaka report notes that they remain stubbornly wedded to their old ways when it comes to using the digital realm for the composition and communication of their research. In other words, somehow it is finally seeming acceptable to use digital media and technology for parts of our work but to resist it in others.

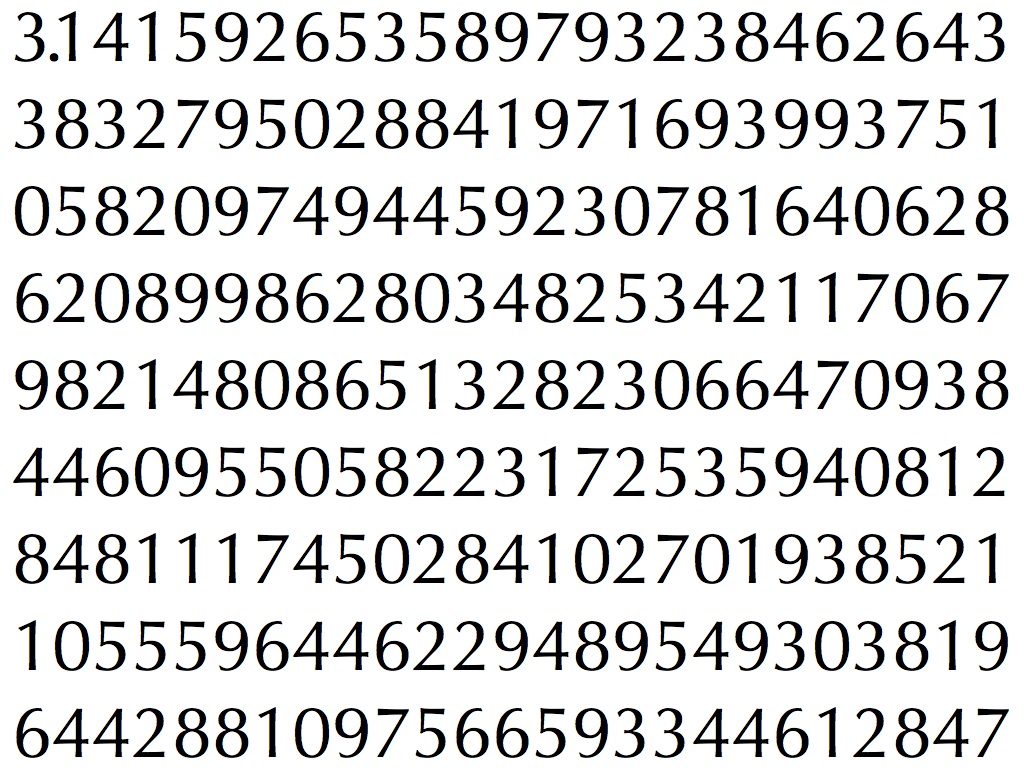

This divide is striking. The professoriate may be more liberal politically than the most latte-filled ZIP code in San Francisco, but we are an extraordinarily conservative bunch when it comes to scholarly communication. Look carefully at this damning chart from the Ithaka report:

Any faculty member who looks at this chart should feel ashamed. We professors care less about sharing our work—even with underprivileged nations that cannot afford access to gated resources—than with making sure we impress our colleagues. Indeed, there was actually a sharp drop in professors who cared about open access between 2003 and the present.

This would be acceptable, I suppose, if we understood ourselves to be ruthless, bottom-line driven careerists. But that’s not the caring educators we often pretend to be. Humanities scholars in particular have taken pride in the last few decades in uncovering and championing the voices of those who are less privileged and powerful, but here we are in the ivory tower, still preferring to publish in ways that separate our words from those of the unwashed online masses.

We can’t even be bothered to share our old finished articles, already published and our reputation suitably burnished, by putting them in an open institutional repository:

I honestly can’t think of any other way to read these charts than as shameful hypocrisy.

4. Narcissism

The irony of this situation is that in the long run it very well may be better for the narcissistic professor in search of reputation to publish in open access venues. When scholars do the cost-benefit analysis about where to publish, they frequently think about the reputation of the journal or press. That’s the reason many scholars consider open access venues to be inferior, because they do not (yet) have the same reputation as the traditional closed-access publications.

But in their cost-benefit calculus they often forget to factor in the hidden costs of publishing in a closed way. The largest hidden cost is the invisibility of what you publish. When you publish somewhere that is behind gates, or in paper only, you are resigning all of that hard work to invisibility in the age of the open web. You may reach a few peers in your field, but you miss out on the broader dissemination of your work, including to potential other fans.

The dirty little secret about open access publishing is that despite the fact that although you may give up a line in your CV (although not necessarily), your work can be discovered much more easily by other scholars (and the general public), can be fully indexed by search engines, and can be easily linked to from other websites and social media (rather than producing the dreaded “Sorry, this is behind a paywall”).

Let me be utterly narcissistic for a moment. As of this writing this blog has 2,300 subscribers. That’s 2,300 people who have actively decided that they would like to know when I have something new to say. Thousands more read this blog on my website every month, and some of my posts, such as “Is Google Good for History?“, garner tens of thousands of readers. That’s more readers than most academic journals.

I suppose I could have spent a couple of years finding traditional homes for longer pieces such as “Is Google Good for History?” and gotten some supposedly coveted lines on my CV. But I would have lost out on the accumulated reputation from a much larger mass of readers, including many within the academy in a variety of disciplines beyond history.

* * *

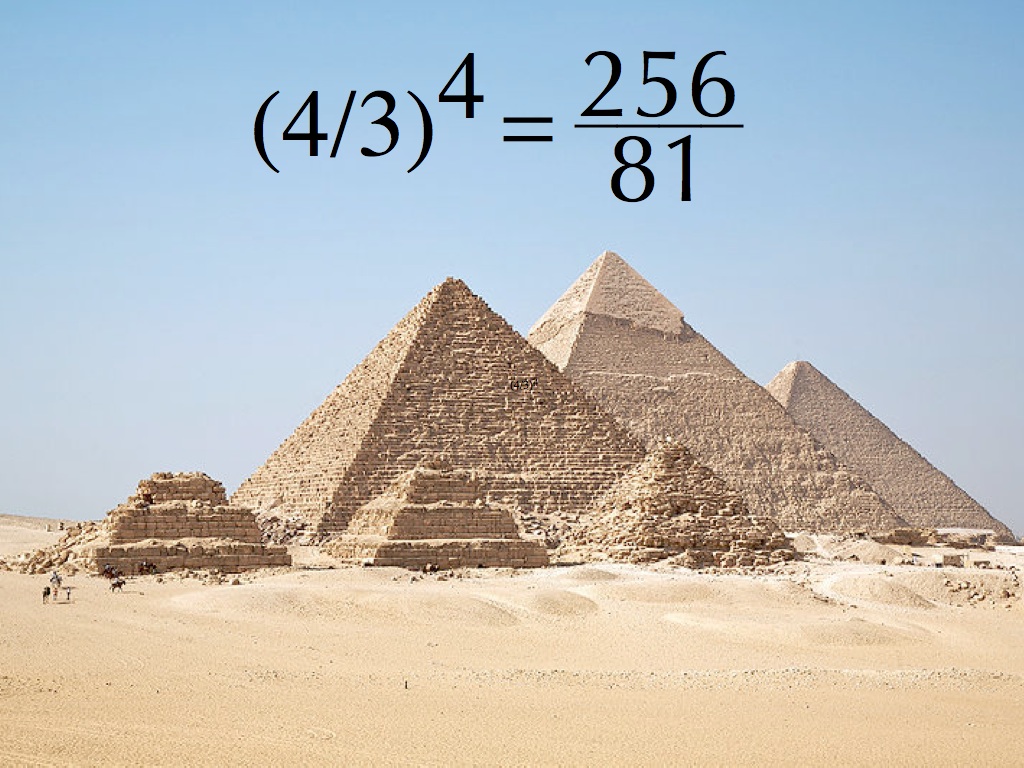

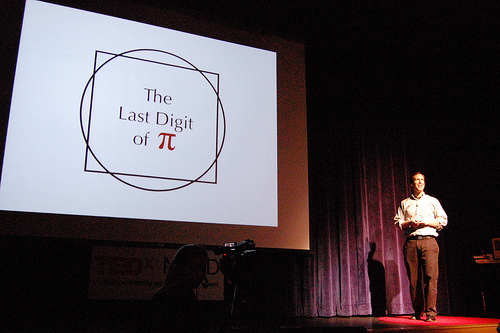

When the mathematician Grigori Perelman solved one of the greatest mathematical problems in history, the Poincaré conjecture, he didn’t submit his solution to a traditional journal. He simply posted it to an open access website and let others know about it. For him, just getting the knowledge out there was enough, and the mathematical community responded in kind by recognizing and applauding his work for what it was. Supply and demand intersected; scholarship was disseminated and credited without fuss over venue, and the results could be accessed by anyone with an internet connection.

Is it so hard to imagine this as a more simple—and virtuous—model for the future of scholarly communication?