With the start of this academic year, I’m launching a new newsletter to explore technology that helps rather than hurts human understanding, and human understanding that helps us create better technology. It’s called Humane Ingenuity, and you can subscribe here. (It’s free, just drop your email address into that link.)

Subscribers to this blog know that it has largely focused on digital humanities. I’ll keep posting about that, and the newsletter will have significant digital humanities content, but I’m also seeking to broaden the scope and tackle some bigger issues that I’ve been thinking about recently (such as in my post on “Robin Sloan’s Fusion of Technology and Humanity“). And I’m hoping that the format of the newsletter, including input from the newsletter’s readers, can help shape these important discussions.

Here’s the first half of the first issue of Humane Ingenuity. I hope you’ll subscribe to catch the second half and all forthcoming issues.

Humane Ingenuity #1: The Big Reveal

An increasing array of cutting-edge, often computationally intensive methods can now reveal formerly hidden texts, images, and material culture from centuries ago, and make those documents available for search, discovery, and analysis. Note how in the following four case studies the emphasis is on the human; the futuristic technology is remarkable, but it is squarely focused on helping us understand human culture better.

Gothic Lasers

If you look very closely, you can see that the stone ribs in these two vaults in Wells Cathedral are slightly different, even though they were supposed to be identical. Alexandrina Buchanan and Nicholas Webb noticed this too and wanted to know what it said about the creativity and input of the craftsmen into the design: how much latitude did they have to vary elements from the architectural plans, when were those decisions made, and by whom? Before construction or during it, or even on the spur of the moment, as the ribs were carved and converged on the ceiling? How can we recapture a decent sense of how people worked and thought from inert physical objects? What was the balance between the pursuit of idealized forms, and practical, seat-of-the-pants tinkering?

In “Creativity in Three Dimensions: An Investigation of the Presbytery Aisles of Wells Cathedral,” they decided to find out by measuring each piece of stone much more carefully than can be done with the human eye. Prior scholarship on the cathedral—and the question of the creative latitude and ability of medieval stone craftsmen—had used 2-D drawings, which were not granular enough to reveal how each piece of the cathedral was shaped by hand to fit, or to slightly shape-shift, into the final pattern. High-resolution 3-D scans using a laser revealed so much more about the cathedral—and those who constructed it, because individual decisions and their sequence became far clearer.

Although the article gets technical at moments (both with respect to the 3-D laser and computer modeling process, and with respect to medieval philosophy and architectural terms), it’s worth reading to see how Buchanan and Webb reach their affirming, humanistic conclusion:

The geometrical experimentation involved was largely contingent on measurements derived from the existing structure and the Wells vaults show no interest in ideal forms (except, perhaps in the five-point arches). We have so far found no evidence of so-called “Platonic” geometry, nor use of proportional formulae such as the ad quadratum and ad triangulatum principles. Use of the “four known elements” rule evidenced masons’ “cunning”, but did not involve anything more than manipulation and measurement using dividers rather than a calibrated ruler and none of the processes used required even the simplest mathematics. The designs and plans are based on practical ingenuity rather than theoretical knowledge.

Hard OCR

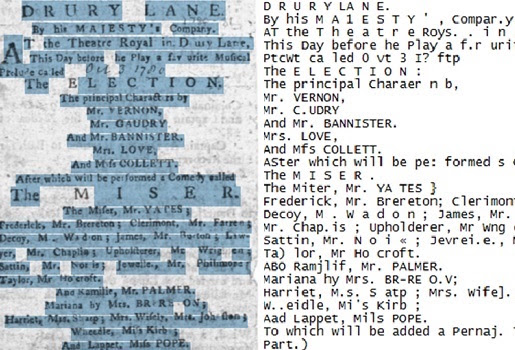

Last year at the Northeastern University Library we hosted a meeting on “hard OCR”—that is, physical texts that are currently very difficult to convert into digital texts using optical character recognition (OCR), a process that involves rapidly improving techniques like computer vision and machine learning. Representatives from libraries and archives, technology companies that have emerging AI tech (such as Google), and scholars with deep subject and language expertise all gathered to talk about how we could make progress in this area. (This meeting and the overall project by Ryan Cordell and David Smith of Northeastern’s NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks, “A Research Agenda for Historical and Multilingual Optical Character Recognition,” was generously funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.)

OCRing modern printed books has become if not a solved problem at least incredibly good—the best OCR software gets a character right in these textual conversions 99% of the time. But older printed books, ancient and medieval written works, writing outside of the Romance languages (e.g., in Arabic, Sanskrit, or Chinese), rare languages (such as Cherokee, with its unique 85-character alphabet, which I covered on the What’s New podcast), and handwritten documents of any kind, remain extremely challenging, with success rates often below 80%, and in some cases as low as 40%. That means 1-3 characters are mistakenly translated by the computer in a five-character word. Not good at all.

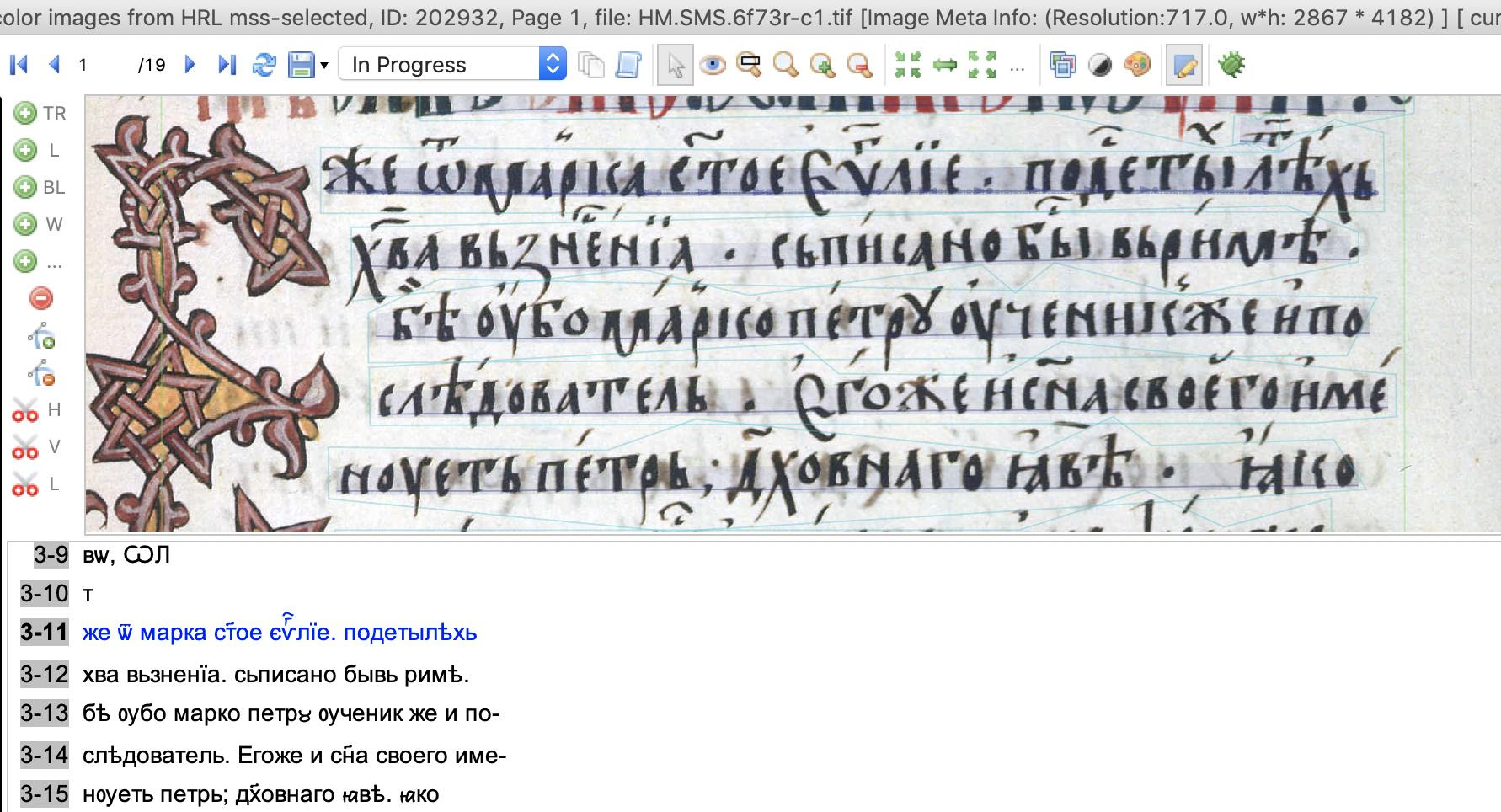

The meeting began to imagine a promising union of language expertise from scholars in the humanities and the most advanced technology for “reading” digital images. If the computer (which in the modern case, really means an immensely powerful cloud of thousands of computers) has some ground-truth texts to work from—say, a few thousand documents in their original form and a parallel machine-readable version of those same texts, painstakingly created by a subject/language expert—then a machine-learning algorithm can be created to interpret with much greater accuracy new texts in that language or from that era. In other words, if you have 10,000 medieval manuscript pages perfectly rendered in XML, you can train a computer to give you a reasonably effective OCR tool for the next 1,000,000 pages.

Transkribus is one of the tools that works in just this fashion, and it has been used to transcribe 1,000 years of highly variant written works, in many languages, into machine-readable text. Thanks to the monks of the Hilandar Monastery, who kindly shared their medieval manuscripts, Quinn Dombrowski, a digital humanities scholar with a specialty in medieval Slavic texts, trained Transkribus in handwritten Cyrillic manuscripts, and calls the latest results from the tool “truly nothing short of miraculous.”

[Again, you can subscribe to Humane Ingenuity to receive the full first issue right here. Thanks.]