I’m delighted that the news is now out about the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation‘s grant to Northeastern University Library to launch the Boston Research Center. The BRC will seek to unify major archival collections related to Boston, hundreds of data sets about the city, digital modes of scholarship, and a wide array of researchers and visualization specialists to offer a seamless environment for studying and displaying Boston’s history and culture. It will be great to work with my colleagues at Northeastern and regional partners to develop this center over the coming years. Having grown up in Boston, and now having returned as an adult, it has a personal significance for me as well.

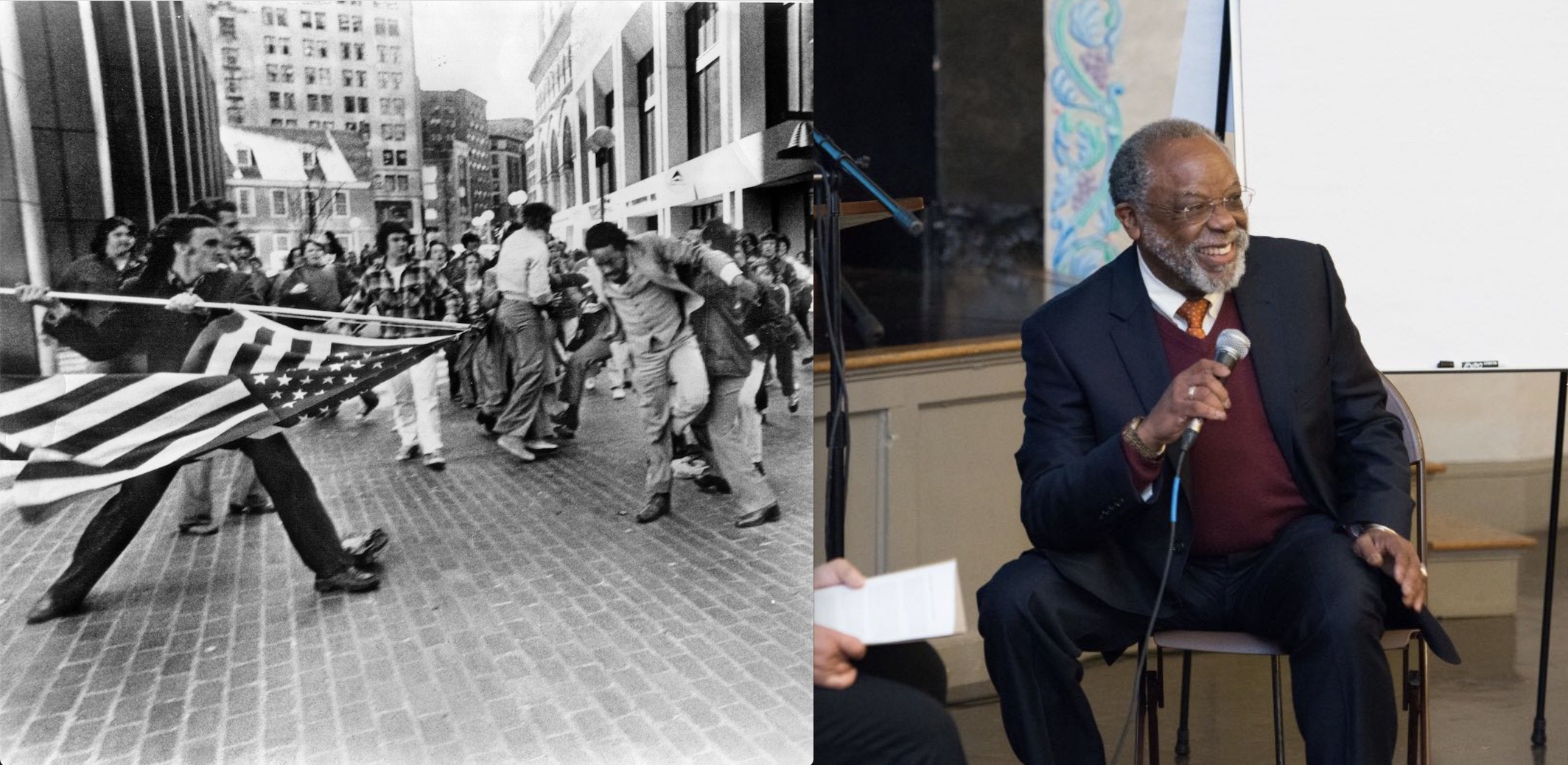

I’m also excited that the BRC will build upon, and combine, some of the signature strengths of Northeastern that drew me to the university last year. For decades, the library has been assembling and working with local communities to preserve materials and stories related to the city. We now have the archives of a number of local and regional newspapers, and the library has been active in the gathering of oral and documentary histories of nearby communities such as the Lower Roxbury Black History Project. We also have strong connections with other important regional collections and institutions, such the Boston Public Library, the Boston Library Consortium, and data sets produced by Boston’s municipal government and other sources, through our campus’s leadership in BARI.

My friends in digital humanities will know that Northeastern has a world-class array of faculty and researchers doing cutting-edge, interdisciplinary computational analysis. We have the NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks, the Network Science Institute, numerous faculty in our College of Arts, Media, and Design who work on digital storytelling and information design, and the library has its own terrific Digital Scholarship Group and dedicated specialists in GIS and data visualization. We will all be working together, and with many others from beyond the university, to imagine and develop large-scale projects that examine major trends and elements of Boston, such as immigration, neighborhood transformations, economic growth, and environmental changes. There will also be an opportunity for smaller-scale stories to be documented, and of course the BRC itself will be open to anyone who would like to research the city or specific communities. As a place with a long and richly documented history, with a coastal location and educational, scientific, and commercial institutions that have long involved global relationships, the study of Boston also means the study of themes that are broadly important and applicable.

My thanks to the Mellon Foundation for their generous support. It should be fascinating to watch all of this come together—stay tuned.