[Thoughts prompted by an invitation to write a piece on the significance of “Notes, Lists, and Everyday Inscriptions” for The New Everyday, an innovative experiment in web publishing sponsored by MediaCommons. Since the editors of this edition of The New Everyday asked for something out of the ordinary for their curated collection, I thought it was time to unveil my Gladwell-esque theory of how criminal profiling and archival priorities share a mathematical foundation.]

How important are small written ephemera such as notes, especially now that we create an almost incalculable number of them on digital services such as Twitter? Ever since the Library of Congress surprised many with its announcement that it would accession the billions of public tweets since 2006, the subject has been one of significant debate. Critics lamented what they felt was a lowering of standards by the library—a trendy, presentist diversion from its national mission of saving historically valuable knowledge. In their minds, Twitter is a mass of worthless and mundane musings by the unimportant, and thus obviously unworthy of an archivist’s attention. The humorist Andy Borowitz summarized this cultural critique in a mocking headline: “Library of Congress to Acquire Entire Twitter Archive; Will Rename Itself ‘Museum of Crap.’”

Few readers of this blog will be surprised to find that I take a rather different view of the matter. How could we not want to preserve a vast record of everyday life and thoughts from tens of millions of people, however mundane? (For more on my views of the Twitter/Library of Congress debate, and to inflate my ego, please consult articles from the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Slate.)

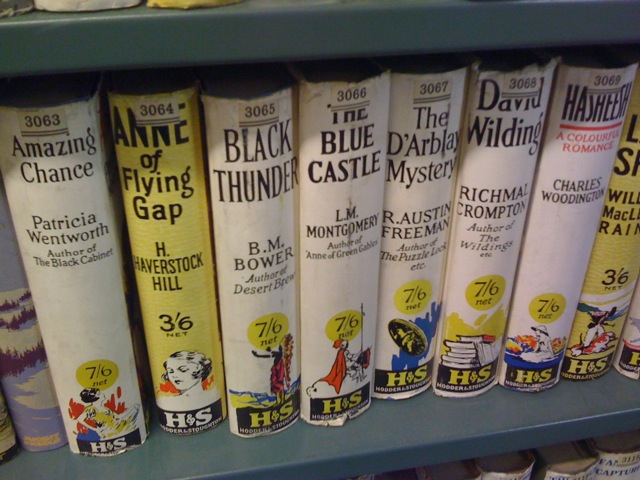

As any practicing historian knows, some of the most critical collections of primary sources are ephemera that someone luckily saved for the future. For example, historians of the English Civil War are deeply thankful that Humphrey Bartholomew had the presence of mind to save 50,000 pamphlets (once considered throwaway pieces of hack writing) from the seventeenth century and give them to a library at Oxford. Similarly, I recently discovered during a behind-the-scenes tour of the Cambridge University Library that the library’s off-limits tower, long rumored by undergraduates to be filled with pornography, is actually stocked with old genre fiction such as Edwardian spy novels. (See photographic evidence, below.) Undoubtedly the librarians of 1900 were embarrassed by the stuff; today, social historians and literary scholars can rejoice that they didn’t throw these cheap volumes out. As I have argued in this space, scholars have uses for archives that archivists cannot anticipate.

But let me set aside for a moment my optimistic disposition about the Twitter archive and instead meet the critics halfway. Suppose that we really don’t know if the archive will be useful or not—or worse, perhaps we are relatively sure it will be utterly worthless. Does that necessarily mean that the Library or Congress should not have accessioned it? I was thinking about this fair-minded version of the “What to save?” conundrum recently when I remembered a penetrating article about criminal profiling, which, of all things, helpfully reveals the correct calculus about the importance of digital ephemera such as tweets.

* * *

The act of stopping certain air travelers for additional checks—to give them more costly attention—is a difficult task riven by conflicting theories of whom to check and (as mathematicians know) associated search algorithms. Do utterly random checks work best? Should the extra searches focus on certain groups or certain bits of information (one-way tickets, cash purchases)? Many on the right (which is also home, I suspect, to many of the critics who scoff at the Twitter archive) believe in strong profiling—that is, spending nearly the entire budget and time of the Transportation Security Administration profiling Middle Easterners and Muslims. Many on the left counter that this strong profiling leads to insidious stereotyping.

A more powerful critique of strong profiling was advanced last year by the computational statistician William Press in “Strong Profiling is Not Mathematically Optimal for Discovering Rare Malfeasors” (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009). Press acknowledges that the issue of profiling (whether for terrorists at the airport or for criminals in a traffic stop) has enormous social and political implications. But he seeks to answer a more basic question: does strong profiling actually work? Or is there a more optimal mathematical formula for spending scarce time and resources to achieve the desired outcome?

Press examines two idealized mathematical cases. The first, the “authoritarian” strategy, assumes that we have perfect surveillance of society and precisely know the odds that someone will be a criminal (and thus worthy of additional screening). The second, the “democratic” strategy, assumes that our knowledge of people is messy and incomplete. In that case of imperfect information the mathematics is much more complex, because we can’t assign a reliable probability of criminality to each person and then give them security attention at an intensity commensurate to that value. It turns out that in the democratic case, the fuzzier mathematics strongly suggest a broader range of attention.

Moreover, even beyond the obvious fact that that the democratic model is closest to real life, the democratic algorithm for profiling is better than the authoritarian model, even if that state of omnipotent knowledge was achievable. Even if we had Minority Report-style knowledge, or even if we believed that the universe of potential criminals was entirely a subset of a particular group, it would be unwise to fully rely on this knowledge. To do so would lead to “oversampling,” an inefficient overemphasis on particular individuals. Of course we should pay attention to those with the maximum probability of being a criminal. But we also have to mix into our algorithm some attention to those who are seemingly innocent to achieve the best outcome—to stop the most crimes.

Through some mathematics we need not get into here, Press concludes that the optimal formula for paying attention to subjects is to avoid using the straight probability that each person is a criminal and instead use the square root of that value. For instance, if you feel Person A is 100 times more likely to be a terrorist than Person B, you should spend 10 times, not 100 times, the resources on Person A over Person B. Moreover, as our certainty about potential suspects decreases, the democratic sampling model becomes increasingly more efficient compared to the authoritarian model.

Although couched in the language of crime prevention, what Press is really talking about is the calculus of importance. As Press himself notes, “The idea of sampling by square-root probabilities is quite general and can have many other applications.”

* * *

As it turns out, the calculus of importance is the same for the Transportation Security Administration and for the Library of Congress. Press’s conclusions apply directly to the archivist’s dilemma of how to spend limited resources on saving objects in a digital age. The criminals in our library scenario are people or documents likely to be important to future researchers; innocents are those whom future historians will find uninteresting. Additional screening is the act of archiving—that is, selection for greater attention.

What does this mean for the archiving of digital emphemera such as status updates—those little, seemingly worthless online notes? It means we should continue to expend the majority of resources on those documents and people of most likely future interest, but not to the exclusion of objects and figures that currently seem unimportant.

In other words, if you believe that the notebooks of a known writer are likely to be 100 times more important to future historians and researchers than the blog of a nobody, you should spend 10, not 100, times the resources in preserving those notebooks over the blog. It’s still a considerable gap, but much less than the traditional (authoritarian) model would suggest. The calculus of importance thus implies that libraries and archives should consciously pursue contents such as those in the Cambridge University Library tower, even if they feel it runs counter to common sense.

So even if the skeptics are right and the Twitter archive is a boondoggle for the Library of Congress, it is the correct kind of bet on the future value of digital ephemera, the equivalent of the TSA spending 10% of their budget to examine more closely threats other than those posed by twentysomething Arabs.

The accessioning of the Twitter archive by the Library of Congress is not an expensive affair. Tweets are small digital objects, and even billions of them fit on a few cheap drives. Even with digital asset management, IT labor across time, and electricity costs, storing billions of tweets is economical, especially compared to the cost of storing physical books. University of Michigan Librarian Paul Courant has calculated [Word doc] that the present value of the cost to store a book on library shelves in perpetuity is about $100 (mostly in physical plant costs). An equivalent electronic text costs just $5.

This vast disparity only serves to reinforce the calculus of importance and archival imperatives of institutions such as the Library of Congress. The library and other keepers of our cultural heritage should be doing much more to save the digital ephemera of our age, no matter what we contemporaries think of these scrawls on the web. You never know when a historian will pan a bit of gold out of that seemingly worthless stream.