It is far too early to understand what happened in this historic year of 2020, but not too soon to grasp what we will write that history from: data—really big data, gathered from our devices and ourselves.

Sometimes a new technology provides an important lens through which a historical event is recorded, viewed, and remembered. When the September 11 Digital Archive gathered tens of thousand stories and photographs from 9/11 (I was involved with the project twenty years ago), it became clear that in addition to the mass medium of television, this tragic day was experienced in a more personal way by many Americans through the earpieces of cellphones and the tiny screens of low-resolution digital cameras. These technologies had only recently reached widespread adoption, but they were quickly pressed into service for communication and documentation, for frantic calls and messages, and as repositories of grainy photographs snapped in the moment.

Over the last two decades, of course, these nascent technologies matured and merged into the smartphone, added GPS and other sensors, and then hosted apps that helped themselves, with our consent and without, to location data, photos, and text. All of this information was then stored and aggregated in ways that were only vaguely conceivable in 2001.

Our year of 2020—somehow simultaneously overstuffed but also stretched thin, a year of Covid and protests against racism and a momentus election—will thus have a commensurately unwieldy digital historical record, densely packed with every need, opinion, and stress that our devices and sensors have captured and transmitted. That the September 11 Digital Archive collected 150,000 born-digital objects will strike future historians as confusingly slight, a desaturated daguerreotype compared to today’s hi-def canvas of data, teeming with vivid pixels. This year we will have generated billions of photographs, messages, and posts. Our movement through time and space has been etched as trillions of bytes about where we went and ate and shopped, or how much we hunkered down at home instead. But even if we hid from the virus, none of us will have been truly hidden. It’s all there in the data.

And it is not just the glowing rectangles we carry with us, through which we see and are seen, that will have produced and received an almost incalculable mass of data. In the testing and treatment of Covid, and the quest for a cure, scientists and doctors will have produced a detailed medical almanac from tens of millions of people, storing biological samples of blood and mucus and DNA for analysis, not just in the present, but also in decades to come.. “For life scientists, the freezer is the archive,” Joanna Radin, a historian of medicine at Yale, recently noted on a panel on “Data Histories of Health” at the Northeastern University Humanities Center.

Databases in the cloud and on ice: this is the record of 2020.

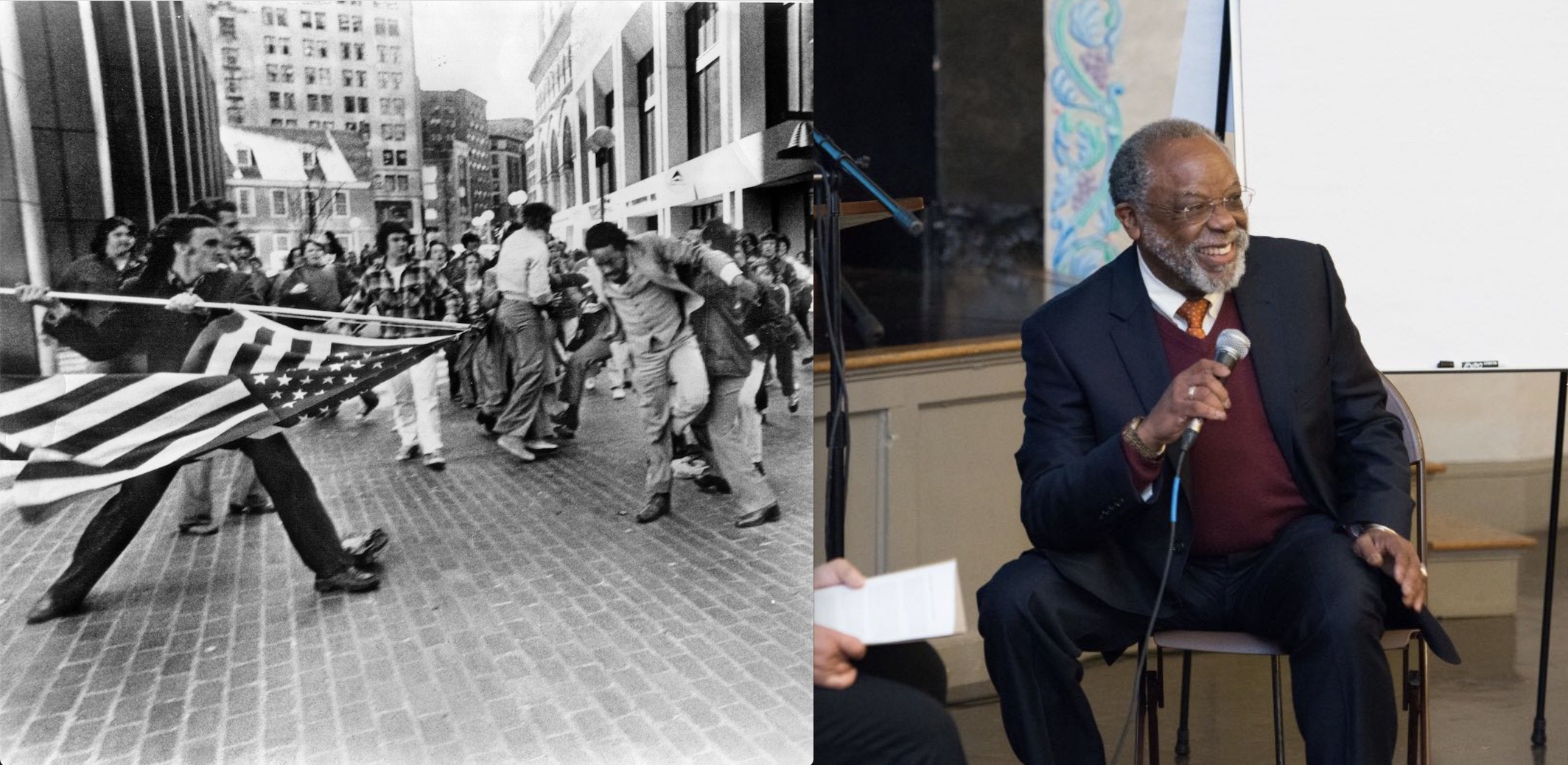

Some of the data we have collected in the present will form the basis for future investigations and understanding. One of those critical and lasting data sets, the Covid Tracking Project, led not by technologists but by humanists, will undoubtedly tell us a great deal about how different states approached the novel coronavirus with caution or carelessness. Contact tracing has created the possibility of network analyses of the interactions of people at a scale never seen before. The Documenting the Now project forged tools to allow for the ethical archiving of social media posts, which was used to gather the collective outpouring of social movements like Black Lives Matter. If the President’s tweets dominated the national news, DocNow collections will present a more democratic expressive history.

While each of these data sets contains vast information, in novel combinations they will prove especially revealing, as correlations between activity and illness, sentiments and social movements, become more apparent. Databases are structured so as to be joined; there will be debates over such syntheses and who gets to do them.

We also learned this year that our privacy is repeatedly violated to create darker archives. Code hidden within seemingly innocuous software such as weather apps tracked us and handed that information over to unknown third parties. The location pings of smartphones may present an atlas of our mobility, but at what cost? Thorny questions about privacy and ethics will only grow over time, and may rightly occlude the use of some data sets.

Other narratives await, embedded in the data like fossils in amber. My colleagues at the Boston Area Research Institute (BARI) at Northeastern, anticipating the importance of this year, began collecting posts to sites like Craigslist, Airbnb, and Yelp early on, and then preserved these compilations for future researchers. Those researchers will be able to discern which furniture we acquired to work at home, and which furniture we cast off to the curb as relics of the Before Times. They will map where some of us fled to, and the locations we shunned. They will see the kinds of foods that gave us comfort in a takeout bag, and the countless family restaurants that went out of business after surviving for generations through recessions and wars.

The data will uncover, even more than we already know, a great deal about the inequalities of modern America. Data will reveal, as a new report by BARI, the Center for Survey Research, and the Boston Public Health Commission, shows, who had to go to work and who could stay home; who had to take public transportation and who had access to a car; and who had safe access to food, and enough of it.

Appropriately, data was also the lens through which we experienced 2020. Every day we encountered numbers of all shapes and sizes, gazed obsessively at charts of rising cases and grim projections of future deaths, or read polls and forecasts of voting patterns. Like supplicants at Delphi, we strained to understand what these numbers were telling us. We quickly learned new statistical concepts, like R0 — and then just as quickly ignored them.

One of the great ironies of 2020 is likely to be this: In this year in which the record of our existence was encoded in big data, that very same data was opaque to most of us, or was met by disbelief and distrust. We can only hope that those looking back on 2020, many years from now, can make sense of the chaos, using a dense historical record unlike anything that has come before.